Dance Dance Education

Dance Dance Education and Rites of Passage

Dance Dance Education and Rites of Passage

—Lessons learned about the importance of play in sustaining engagement from a high school “girl gamer†based upon socio- and cultural-cognitive analysis for designing instructional environments to elicit and sustain engagement through identity construction.

Brock Dubbels

The Center for Cognitive Sciences, Reading Education

The University of Minnesota, Department of Curriculum & Instruction,

Abstract

The experience of a successful adolescent learner will be described from the student’s perspective about learning the video game Dance Dance Revolution through selected passages from a phenomenological interview van Manen (1997). The question driving this investigation is, “Why did she sustain engagement in learning?†The importance of this question came out of the need for background on how to create an afterschool program that was to use Dance Dance Revolution as an after school activity that might engage adolescents and tweens to become more physically active and reduce the risk of adult obesity, and to increase bone density for these developing young people through playing the game over time. The difficulty of creating this program was the risk that the students would not sustain engagement in the activity, and thus we would not have a viable sample for the bone density adolescent obesity study. Although the phenomenological interview is generally considered a critical social science approach, the interview transcript was also analyzed using methods from critical discourse (Gee, 1992, 1996, 1999; Fairclough, 2007) with a framework developed from Chapman’s (2006) review of engagement, and from: elements of Communities of Practice (Wenger, 1996), Affinity Groups (Gee, 2001), Positive Interdependence (Deutsch 1960; Johnson and Johnson, 1989), and Self-Determination (Ryan and Deci, 2008). These social learning theories are used to explore issues of sustaining engagement through socially distributed reinforcement and to operationalize the ambiguity of identity as a construct into something that might be replicated for designing instruction. Implications of this study include understanding the potential construction of learning environments that motivate and sustain engagement in learning and the importance of identity construction (Buckingham, 2007) for teachers to motivate and engage their students. In addition to the analysis of sustained engagement through the four socio- and cultural-cognitive theories, four major principals were extracted from the operationalized themes into a framework for instructional design techniques and theory for engaging learners for game design, training, and in classroom learning.

Key terms: Dance Dance Revolution, Exergaming, Phenomenology, Identity Construction, Self-Determination Theory, Affinity Groups, Positive Interdependence, Cooperative Learning, Motivation, Engagement, Social Learning, Instructional Design, Rites of Passage, Play, Games, Initiation, Semiotic Domains, Apprenticeship, Transformation.

Introduction

This article seeks to understand what engages young people in learning, and what sustains their interest to continue. It was intended to explore the elements that inform the lived experience of a chosen play activity and the possible social learning theories that might inform it. Four theories were chosen and operationalized for coding the transcript of the phenomenological interview because of their focus on motivation, social learning, and identity construction: Communities of Practice (Wenger, 1998), Affinity Groups (Gee, 2001), Social Interdependence (Deustch, 1962; Johnson and Johnson, 1989) and Self-Determination theory (Deci and Ryan, 2002).

All of these theories seek to explain the motivation behind learning as socially constructed and distributed phenomena; all seek to describe the process of identity construction as an impetus for situated learning. The assumption in this study was that it is through the process of identity construction that engagement is sustained and supported through the process of group affiliation and is distributed through apprenticeship, modeling, group interaction, interdependence, and situated in space.

Identity construction rituals and rites of passage

Traditionally, communities gather to provide ceremony for initiation and status transition for such things as the celebration of status change, where a child becomes an adult, and initiation, where single people become married couple. Although there may be many more transitions and rituals in today’s society because of the great variety of cultural subgroups, i.e., churches, car clubs, self-help groups like Alcoholic Anonymous, and hobby groups like The Peoples’ Revolutionary Knitting Circle, etc.; many of these groups traditionally necessitated face-to-face interaction, but with the internet and today’s computing power, these relations can be mediated digitally through portals such as Facebook, Xbox Live, Second Life, and other social networking tools – as well as expert systems that provide feedback based upon performance, such as a video games like Dance Dance Revolution.

The Dance Dance Revolution game club might be represented as a ritual rite of passage to understand how and why people build identities around their play, and sustain engagement to ultimately develop expertise. Central to the rite of passage is the initiation ritual (Van Gennep, 1960), where new roles and status are conferred through public performance where play (Geertz, 1975), the subjunctive mood (Turner, 1969), situates the activity, so that rules, roles, and consequences are suspended and participants can explore new identities, associated activities, and their semiotic domains and thus develop new status.

With this in mind, well-designed video games and their fan bases may represent and express new forms of the rite of passage and initiation ritual. Like a rite of passage, games are structured activities that are valued by certain cultural sub-groups, depend upon play as a subjunctive mood, represent expert systems that resemble apprenticeship activities, and involve performance initiation. The subjunctive mood observed in games and ritual are said to decontextualize the action and provide a suspension of rules, roles, and consequences found in ordinary life to allow for the exploration of new identities, rules, roles, actions, and social affiliations and status in a safe space. Games can do this well.

The ritual and process of identity construction may be an organizing principle in understanding motivation and engagement. The four social learning theories presented for discourse analysis seek to provide the impetus for motivation and engagement and how to structure it, and rely upon aspects of identity construction; but these theories do not present themselves as descriptions of the identity construction process. Each theory has a different focus and seeks to describe aspects of identity and focus on an element that informs identity construction: Community (Wenger, 1998), Activity (Gee, 2001), how individuals interact with each other (Deustch, 1962; Johnson and Johnson, 1989), and needs of the individual (Deci and Ryan, 2002). For the purposes of this study, these theories were operationalized to provide insight for designing instructional environments that will motivate and sustain the engagement of the learner.

Purpose of study

This interview was to inform design features to develop a program for pre-adolescent exercise with Dance Dance Revolutionfor the study of ob esity reduction and increasing bone density. The study was also intended to get a sense of why a young woman sustained engagement with Dance Dance Revolution over three years to develop expertise, and how educators might replicate that kind of commitment to learning and practice. This study may be especially pertinent to designing instructional contexts, exergaming, and structuring interaction and professional development.

esity reduction and increasing bone density. The study was also intended to get a sense of why a young woman sustained engagement with Dance Dance Revolution over three years to develop expertise, and how educators might replicate that kind of commitment to learning and practice. This study may be especially pertinent to designing instructional contexts, exergaming, and structuring interaction and professional development.

Background of the study

Health care professionals have observed an increase in levels of childhood obesity. This increase has been attributed in large part to physical inactivity. Physical inactivity can lead to obesity and poor cardiovascular health, and it can also have negative effects on bone health. Bones function to support a mechanical load (a force exerted by body weight, muscle, growth, or activity). Bone is constantly formed and reabsorbed throughout life in a generally balanced way. However, in a three- to four-year window during puberty, bone formation is accelerated. In that period, as much bone material is deposited as will be lost during a person’s entire adult life. During these pivotal years of bone development, physical activity is important for optimizing bone health, as it has been shown to reduce the incidence of fractures later in life.

Because it is difficult to motivate children to participate in the type of cardiovascular activities that adults engage in (running, cycling, aerobics), new strategies must be developed, and these may demand elements that motivate the learner to sustain engagement over a longer period of time in order to promote and sustain life habits for physical conditioning.

Dance Dance Revolution is not your typical video game.

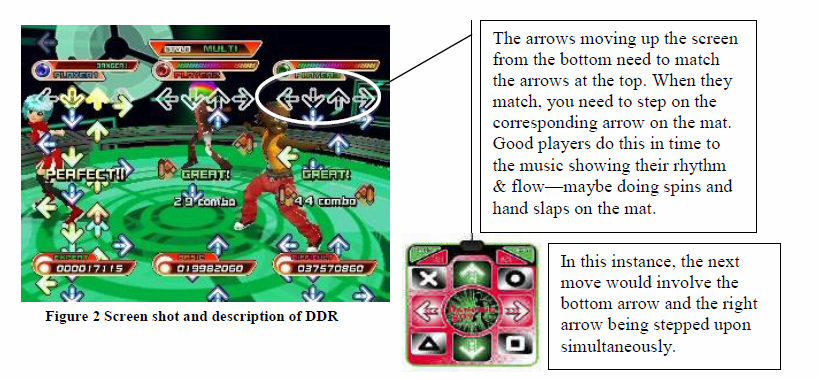

Dance Dance Revolution (DDR) is a game that you set up with mats, a TV, a game console and a game disk, and up to four people can play simultaneously (figure 1). To play DDR, a participant responds to a series of directional arrows, (see figure 2) displayed on a video or TV screen to perform choreographed dance steps or hops synchronized to music. Song tempo and degree of difficulty increase as the player successfully progresses in the game. Because of the game’s popularity and its cardiovascular exercise and jumping (bone-building) components, it could represent an appealing model for reducing physical inactivity in children.

The video dance game Dance Dance Revolution may be a possible solution to increasing activity and mechanical load because of the amount of jumping activity, but the young person must be motivated to start, and engagement must be sustained for the activity to produce valid and reliable measures of obesity and bone density. The issue under investigation was how to help young people start an activity and sustain it; and the simple answer to this was, seemingly, to make it fun; to make it a high-interest activity; but many toys, games, and activities are often tried once and then put aside. What came out of the interview was:

· the importance of aligning the outcomes with a desirable activity,

· autonomy-supporting environments,

· the importance of group and environment to the construction of status and identity that makes belonging to a group desirable along with the sustenance of a common activity;

· the importance of status and relation for reinforcement;

· the centrality of group performance,

· the role of play as a subjunctive mood and portal to engagement,

· and again, the importance of identity construction for transformation to instantiate sustained engagement conveyed through affiliation, apprenticeship, positive interdependence, and expertise. The big idea here is that perception leads to transformation.

Interview-ee/ informant

To explore this, we recruited Ellen as a DDR expert and possible employee to lead an after-school program at one of our sites at the Minneapolis Public Schools. We posted a hiring description for DDR experts and had a number of responses. One respondent, Charles, shared that he had a lot of friends who were really good at DDR, and Ellen was listed as one of those people. Ellen came into the lab to show us her DDR play, and we were impressed with her expertise.

What was interesting about Ellen was that she was not from a subversive or reactionary sub-culture. Ellen is part of one of the least studied cultural sub-group in schools (Buckingham, 2007)—an urban, middle-class teen that is successful in school, is respectful to teachers, has a part-time job, plays varsity soccer, in traveling band, is part of the International Baccalaureate Program, and, has a satisfying home life. These elements of her identity were surprising. We usually assume that video game players are a disenfranchised fringe group at school who do not engage with the typical academic fare. Ellen was able to balance not only her academics and music instruction, work a part-time job, but also play sports and have friendships. These elements of balance were enticing and we wanted to know how she was doing it so that we might try and replicate not only the physical health benefits in our bone density study, but also some of the psycho-social and affective elements necessary for sustaining engagement (Chapman 2003). She seemed like a great role model for creating a curriculum that would rely heavily on identity development and she was an intriguing informant to help us understand how play identities might lead to work habits that help form healthy minds and bodies.

Methodology and review of literature

The question driving this investigation is, “Why did she sustain engagement in learning?†According to Chapman (2006), engagement is more than behavioral time on task. When looking to measure growth or change, or even to understand whether a learner has truly engaged, an educator should also look for evidence of commitment and positive attitudes related to the activity and subject matter.

• Engagement is not just doing the work, it is a connection and an affinity to an activity supported from the affective domains (Chapman, 2003).

• Skinner & Belmont (1993, p.572) report that engaged learners show sustained behavioral involvement in learning activities accompanied by a positive emotional tone, select tasks at the border of their competencies, initiate action when given the opportunity, and exert intense effort and concentration.

• Pintrich and & De Groot (1990, in Chapman) see engagement as having observable cognitive components that can be seen or elicited through exploring the learner’s use of strategy, metacognition, and self-regulatory behavior to monitor and guide the learning processes.

These attributes do not appear in an activity because a student is told that it is good for them, and that they should commit to their betterment. Least likely is that they do an activity because we threaten, or just because we want them to. A student must make a choice to commit to an activity and have that commitment reaffirmed over time to sustain engagement. True engagement in an activity is in some sense transformative and resembles identity construction, in that it changes who one is through cognitive, affective, and behavioral elements. It seems likely that without positive reinforcement (Skinner, 1938) the behavior may result in extinction and the game becomes another resident on the island of misfit toys. We look at social learning theories to explore issues of sustaining engagement through socially distributed reinforcement.

Dance Dance Revolution is considered a high interest activity for many young people, and it does have a reward system that gives real-time feedback on performance with rewards for successfulplay. But, without aligning those rewards and achievement with social capital, they lack meaning and status, and the reinforcement system remains a token economy (Ferster and Skinner, 1957) whose tokens are unredeemable except as social capital. The work of Buckingham on identity development may provide some insight for connecting identity with purpose, motivation, and sustained engagement. Buckingham (2008, p. 3) states that

Identity is developed by the individual, but it has to be recognized and

confirmed by others. Adolescence is also a period in which young people

negotiate their separation from their family, and develop independent

social competence (for example, through participation in “cliques†and

larger “crowds†of peers, who exert different kinds of influence).

Identity and status were traditionally conferred through rites of passage, and there may have been many culturally-specific instances of these rites for different groups and related activities. Video games may represent a new wrinkle in the way that we enact and view rites of passage. They may offer a form of guided, ritualized behavior for identity construction and group affiliation as an autonomy-supporting environment (Ryan & Deci, 1999), Affinity Group (Gee, 2001), Social Interdependence (Deutsch 1960; Johnsons and Johnson 1989) or Community of Practice (Wenger, 1998).

A rite of passage does not need to resemble the tribal practices that led to vision quests, ritual markings, or exodus. A rite of passage may be organized in three forms: the process of separation, transition, and integration, (Van Gennep, 1960), but all three of these rites may also be presented as single rite (Barnard and Spencer, 1996). What was important for Van Gennep was the idea of Liminality, or the threshold. The threshold in an initiation represents a portal – a representative movement from the status of one social space to another, where ritualistically, the individual or group makes a transition by passing through a metaphorical or literal portal to represent a change in social status and position.

In the context of Liminality, the activity space may be far removed from reality, and roles, rules, tools, values, and status may be situated in the flux of play as if a hybrid or interstitial space (Turner, 1969). This concept of the threshold and liminality seems to validate Geertz (1972) and his description of the “Center Bet” in describing the ritual of Balinese Cockfighting and Benthams’ concept of Deep Play. According to Turner (1969), there may be many rites of passage in a person’s life through sub-cultural affiliation (Cock Fighting, DDR, First Job) where identity and entitlement are inculcated through desire to become a respected and acknowledged group member, where the individual can share in and contribute to group activity, participate in group spaces, and publicly renew and further their status.

For Wenger, (1998) identity is central to human learning; identity construction and learning are distributed through community and relations; learning is socially constructed; and motivation is based on a desire for sharing and participatory culture. The work of Wenger shares many attributes with Gee’s work, but the focus for Wenger was on socially distributed cognition and learning as social participation. Earlier work (Lave & Wenger, 1991) explored the role of learning in apprenticeship, where newcomers would enter into a space where learning was situated and contextualized, and goals and purpose were evident due to entering the space. One entered the space to gain apprenticeship and attempt to acquire and learn the sociocultural practices of the community. Thus, the individual is drawn to the group and begins to engage and learn by finding their role in a distributed, networked, cultural-cognitive process with the purpose of the individual as an active participant in the practices of a social community and become an acknowledged member with skills, knowledge, and the requisite values. This participation leads to the construction of his/her identity through these communities. From this understanding develops the concept of the Community of Practice: a group of individuals participating in communal activity– creating their shared identity through engaging in and contributing to the practices of their communities.

The difficulty with this theory is that group membership is hard to define. A person may want to be part of group and claim group membership, but not have the identifiable characteristics that define the membership. Since identity is conferred from others, there are factors that can identify a person as a group member and as having identity markings. For Gee (2001), the activity is primary and provides the motivation and engagement, the source of group membership and the identity markings; for Gee the community and relations are ancillary and stem from the interaction related to the activity. He states that these communities and spaces are hard to identify without knowing exactly why people are there. Whether a person actually claims group membership or is acknowledged can be difficult.

For Gee, whether group membership is acknowledged — claimed or not — attributes can still be observed. The role of Gee’s work is central to operationalizing identity and group membership through offering observable sociocultural markers that come from semiotic domains central to the activity as evidence of group membership.

A semiotic domain recruits one or more modalities (e.g., oral or written language,

images, equations, symbols, sounds, gestures, graphs, artifacts, and so forth) to

communicate distinctive types of messages. By the word “fluent†I mean that the

learner achieves some degree of mastery, not just rote knowledge. . . Semiotic

domains are, of course, human creations. As such, each and every one of them is

associated with a group of people who have differentially mastered the domain, but

who share norms, values, and knowledge about what constitutes degrees of mastery

in the domain and what sorts of people are, more or less, “insiders†or “outsidersâ€.

Such a group of people share a set of practices, a set of common goals or endeavors,

and a set of values and norms, however much each of the individuals in the group may

also have their own individual styles and goals, as well as other affiliations.

Gee (2001, pg. 2).

This work allows for certain attributes of group membership to be observable rather than subjective. A young person may have grown up participating in an activity with parents and young friends, but during the puberty years, may reject that affiliation based upon new goals for group membership and status. A new group may be more desirable than a current group, and the young person may cast off markings that identify them with the old group such as a hat from a uniform, ways of speaking, values, etc. This does not mean that markings of prior group membership with parents, family, and childhood affiliations are not still observable—an accent or mannerism may indicate origins or influence. For Gee (2001) it is the activities and the group practices that provide evidence of social learning and group membership from semiotic domains, and it is activity that is central to identity construction.

For Deci and Ryan (2002) the focus comes from work on motivation with a focus on Autonomy — possibly built from early work by White (1959), where organisms have an innate need to experience competence and agency, and experience joy and pleasure with the new behaviors when they assert competence over the environment . . . what White called effectance motivation. For Deci and Ryan motivation is based on the degree that an activity or value has been internalized, and this is based upon the degree to which the behavior has meaning within the context of the arena of performance.

In order to sustain engagement for Deci and Ryan, motivation must be internalized . . . the external contingency must be “swallowed whole.†The learner identifies the value of the new behavior with other values that are part of the self. This process of engagement is the transformation of an extrinsic motive, one that is reinforced from outside the learner’s values, into an activity that is assimilated and internalized by the learner as an intrinsic value that becomes part of their personal identity. This process involves constructing values aligned with the group and environment, and thus assimilates behavioral norms that were originally external as part of a new identity. Based on the degree of control exerted by external factors, levels of extrinsic motivation can be aligned along a continuum.

Be sure to look for the article when it comes out.

Other sections include:

-

-

-

-

-

Themes for coding

-

Play as Subjunctive Mood, Activity Space, Desirable Social Grouping, and Desirable Activity

-

Data collection

-

Data Analysis

-

Interview

-

The performance/ initiation

- Conclusion

- Relevance of analysis

- Implications / lessons for designing instructional environments

- Principle 1 — Play as a Subjunctive Mode

- Principle 2 — Desirable Activities

-

Principle 3 — Spaces

-

Principal 4 – Desirable Groups

- Appendices

- Works Cited

-

-

-

-

Introduction

This article seeks to understand what engages young people in learning, and what sustains their interest to continue. It was intended to explore the elements that inform the lived experience of a chosen play activity and the possible social learning theories that might inform it. Four theories were chosen and operationalized for coding the transcript of the phenomenological interview because of their focus on motivation, social learning, and identity construction: Communities of Practice (Wenger, 1998), Affinity Groups (Gee, 2001), Social Interdependence (Deustch, 1962; Johnson and Johnson, 1989) and Self-Determination theory (Deci and Ryan, 2002).

All of these theories seek to explain the motivation behind learning as socially constructed and distributed phenomena; all seek to describe the process of identity construction as an impetus for situated learning. The assumption in this study was that it is through the process of identity construction that engagement is sustained and supported through the process of group affiliation and is distributed through apprenticeship, modeling, group interaction, interdependence, and situated in space.

Identity construction rituals and rites of passage

Traditionally, communities gather to provide ceremony for initiation and status transition for such things as the celebration of status change, where a child becomes an adult, and initiation, where single people become married couple. Although there may be many more transitions and rituals in today’s society because of the great variety of cultural subgroups, i.e., churches, car clubs, self-help groups like Alcoholic Anonymous, and hobby groups like The Peoples’ Revolutionary Knitting Circle, etc.; many of these groups traditionally necessitated face-to-face interaction, but with the internet and today’s computing power, these relations can be mediated digitally through portals such as Facebook, Xbox Live, Second Life, and other social networking tools – as well as expert systems that provide feedback based upon performance, such as a video games like Dance Dance Revolution.

The Dance Dance Revolution game club might be represented as a ritual rite of passage to understand how and why people build identities around their play, and sustain engagement to ultimately develop expertise. Central to the rite of passage is the initiation ritual (Van Gennep, 1960), where new roles and status are conferred through public performance where play (Geertz, 1975), the subjunctive mood (Turner, 1969), situates the activity, so that rules, roles, and consequences are suspended and participants can explore new identities, associated activities, and their semiotic domains and thus develop new status.

With this in mind, well-designed video games and their fan bases may represent and express new forms of the rite of passage and initiation ritual. Like a rite of passage, games are structured activities that are valued by certain cultural sub-groups, depend upon play as a subjunctive mood, represent expert systems that resemble apprenticeship activities, and involve performance initiation. The subjunctive mood observed in games and ritual are said to decontextualize the action and provide a suspension of rules, roles, and consequences found in ordinary life to allow for the exploration of new identities, rules, roles, actions, and social affiliations and status in a safe space. Games can do this well.

The ritual and process of identity construction may be an organizing principle in understanding motivation and engagement. The four social learning theories presented for discourse analysis seek to provide the impetus for motivation and engagement and how to structure it, and rely upon aspects of identity construction; but these theories do not present themselves as descriptions of the identity construction process. Each theory has a different focus and seeks to describe aspects of identity and focus on an element that informs identity construction: Community (Wenger, 1998), Activity (Gee, 2001), how individuals interact with each other (Deustch, 1962; Johnson and Johnson, 1989), and needs of the individual (Deci and Ryan, 2002). For the purposes of this study, these theories were operationalized to provide insight for designing instructional environments that will motivate and sustain the engagement of the learner.

Purpose of study

This interview was to inform design features to develop a program for pre-adolescent exercise with Dance Dance Revolution for the study of obesity reduction and increasing bone density. The study was also intended to get a sense of why a young woman sustained engagement with Dance Dance Revolution over three years to develop expertise, and how educators might replicate that kind of commitment to learning and practice. This study may be especially pertinent to designing instructional contexts, exergaming, and structuring interaction and professional development.

Background of the study

Health care professionals have observed an increase in levels of childhood obesity. This increase has been attributed in large part to physical inactivity. Physical inactivity can lead to obesity and poor cardiovascular health, and it can also have negative effects on bone health. Bones function to support a mechanical load (a force exerted by body weight, muscle, growth, or activity). Bone is constantly formed and reabsorbed throughout life in a generally balanced way. However, in a three- to four-year window during puberty, bone formation is accelerated. In that period, as much bone material is deposited as will be lost during a person’s entire adult life. During these pivotal years of bone development, physical activity is important for optimizing bone health, as it has been shown to reduce the incidence of fractures later in life.

Health care professionals have observed an increase in levels of childhood obesity. This increase has been attributed in large part to physical inactivity. Physical inactivity can lead to obesity and poor cardiovascular health, and it can also have negative effects on bone health. Bones function to support a mechanical load (a force exerted by body weight, muscle, growth, or activity). Bone is constantly formed and reabsorbed throughout life in a generally balanced way. However, in a three- to four-year window during puberty, bone formation is accelerated. In that period, as much bone material is deposited as will be lost during a person’s entire adult life. During these pivotal years of bone development, physical activity is important for optimizing bone health, as it has been shown to reduce the incidence of fractures later in life.

![]() Because it is difficult to motivate children to participate in the type of cardiovascular activities that adults engage in (running, cycling, aerobics), new strategies must be developed, and these may demand elements that motivate the learner to sustain

Because it is difficult to motivate children to participate in the type of cardiovascular activities that adults engage in (running, cycling, aerobics), new strategies must be developed, and these may demand elements that motivate the learner to sustain

engagement over a longer period of time in order to promote and sustain life habits for physical

conditioning.

conditioning.

|

![]()

Dance Dance Revolution is not your typical video game.

Dance Dance Revolution (DDR) is a game that you set up with mats, a TV, a game console and a game disk, and up to four people can play simultaneously (figure 1). To play DDR, a participant responds to a series of directional arrows, (see figure 2) displayed on a video or TV screen to perform choreographed dance steps or hops synchronized to music. Song tempo and degree of difficulty increase as the player successfully progresses in the game. Because of the game’s popularity and its cardiovascular exercise and jumping (bone-building) components, it could represent an appealing model for reducing physical inactivity in children.

![]() The video dance game Dance Dance Revolution may be a possible solution to increasing activity and mechanical load because of the amount of jumping activity, but the young person must be motivated to start, and engagement must be sustained for the activity to produce valid and reliable measures of obesity and bone density.

The video dance game Dance Dance Revolution may be a possible solution to increasing activity and mechanical load because of the amount of jumping activity, but the young person must be motivated to start, and engagement must be sustained for the activity to produce valid and reliable measures of obesity and bone density.

The issue under investigation was how to help young people start an activity and sustain it; and the simple answer to this was, seemingly, to make it fun; to make it a high-interest activity; but many toys, games, and activities are often tried once and then put aside. What came out of the interview was:

· the importance of aligning the outcomes with a desirable activity,

· autonomy-supporting environments,

· the importance of group and environment to the construction of status and identity that makes belonging to a group desirable along with the sustenance of a common activity;

· the importance of status and relation for reinforcement;

· the centrality of group performance,

· the role of play as a subjunctive mood and portal to engagement,

· and again, the importance of identity construction for transformation to instantiate sustained engagement conveyed through affiliation, apprenticeship, positive interdependence, and expertise. The big idea here is that perception leads to transformation.

[…] Go here to read the rest:Â Dance Dance Education | Video Games As Learning Tools […]