Why Video Games Sustain Engagement: A Cage Match between Social Learning Theories

Why Video Games Sustain Engagement: A Cage Match between Social Learning Theories

Brock Dubbels

The Center for Cognitive Sciences

Department of Curriculum & Instruction

The University of Minnesota

Abstract: Although games are seen as high interest activities, many children buy them, play them, and move on to another activity. This represents a challenge in creating instructional interventions to achieve an educational outcome or a training effect. This study was conducted to inform an after school program designed to deliver a training effect on female adolescent health. To investigate this, a small sample of young female experts were recruited and interviewed for rich phenomenological descriptions (van Manen, 2002) to examine the aspects engagement as described by (Chapman 2006) as informed through identity construction (Buckingham, 2007, Van Gennep, 1960; Turner, 1969). Interview transcripts were coded and analyzed using methods from discourse analysis (Gee, 1992, 1996, 1999; Fairclough, 2007) using themes from social learning theories such as Communities of Practice (Wenger, 1996), Affinity Groups (Gee, 2001), Positive Interdependence (Deutsch, 1962, Johnson & Johnson, 1989), and Self-Determination (Ryan and Deci, 2008). Implications of this study include understanding the importance of identity construction to motivate and sustain engagement in learning.

Key terms: Dance Dance Revolution, Phenomenology, Identity Construction, Self-Determination Theory, Affinity Groups, Motivation, Engagement, Social Learning, Instructional Design, Rites of Passage, Play, Games, Initiation, Semiotic Domains, Apprenticeship, Transformation.

Citation:

Dubbels, B.R. (2010) Designing Learning Activities for Sustained Engagement — Four Social Learning Theories Coded and Folded into Principals for Instructional Design through Phenomenological Interview and Discourse Analysis. In Discoveries in Gaming Research. IGI Global Publishers.

Introduction

This article seeks to understand what engages young people in learning, and what sustains their interest to continue. It was intended to explore the elements that inform the lived experience of a chosen play activity and examine the possible social learning theories that might inform it. Five social learning theories were examined to ground the aspects engagement as described by (Chapman 2006) and informed through social learning theories such as Communities of Practice (Wenger, 1996), Affinity Groups (Gee, 2001), Positive Interdependence (Deutsch, 1962, Johnson & Johnson, 1989), and Self-Determination (Ryan and Deci, 2008). Implications of this study include understanding the importance of identity construction to motivate and sustain engagement in learning (Buckingham, 2007, Van Gennep, 1960; Turner, 1969).

All of the theories listed above seek to explain the motivation behind learning as socially constructed and distributed phenomena; all seek to describe the process of identity construction as an impetus for situated learning. The assumption in this study was that it is through the process of identity construction that engagement is sustained and supported through the process of group affiliation and is distributed through apprenticeship, modeling, and group interaction.

| Social Learning Theory | Scale/Application | Author(s) |

| Engagement | Aggregate | Chapman, 2006 |

| Communities of Practice | Structural Social | Wenger, 1996 |

| Positive Interdependence | Structural Social | Deutsch, 1962, Johnson & Johnson, 1989; Johnson and Holubec, 1998), |

| Affinity Groups | Structural Social | Gee, 2001 |

| Self-Determination | Social Psychological | Deci and Ryan, 2008 |

Identity construction may be an organizing principle in understanding motivation and engagement, and yet these social learning theories do not present themselves as descriptions of the identity construction process, but rather focus on structural factors in relationships Community (Wenger, 1998), (Deutsch, 1962, Johnson & Johnson, 1989; Johnson, Johnson and Holubec, 1998), Activity (Gee, 2001), and needs of the individual (Deci and Ryan, 2008) as organizing principles. For the purposes of this study, these theories were operationalized to provide insight for designing instructional environments that will motivate and sustain the engagement of the learner. It was predicted that identity construction would predict motivation and engagement. This prediction was based upon the recurrence of the theme throughout the social learning theories. The act of identity construction is an act of becoming, Not only do individuals construct a unique description of themselves as an identity, but it I also conferred upon them and reinforced through context, including age, personal history, relationships and history, location, and community status.

Identity construction rituals and rites of passage

Traditionally, communities gather to provide ceremony for initiation and status transition for such things as the celebration of status change from child to adult; initiation single people to married couple; and a multitude of culturally mediated roles, acknowledgement, and transitions. Although there may be many more transitions and ritual’s in today’s society because of the great variety of cultural subgroups, i.e. churches, car clubs, self-help groups like Alcoholic Anonymous, and hobby groups like The Peoples’ Revolutionary Knitting Circle, etc.; many of these groups traditionally necessitated face to face interaction, but with the internet and today’s computing power, these relations can be mediated digitally through portals such as Facebook, Xbox Live, Second Life, and other social networking tools.

The Dance Dance Revolution game club might be represented as a ritual rite of passage to understand how and why people build identities around their play, and sustain engagement to ultimately develop expertise. Central to the rite of passage is the initiation ritual (Van Gennep, 1960), where new roles and status are conferred through public performance where play, the subjunctive mood (Turner, 1969), situates the activity, so that rules, roles, and consequences are suspended and participants can explore new identities, associated activities, and their semiotic domains and develop new status.

With this in mind, video games may represent new forms of the rite of passage and initiation ritual; games are structured activities that are valued by certain cultural sub-groups, represent expert systems that resemble apprenticeship activities, involve performance initiation, and with similar emphasis on what Sutton-Smith (1976) called the play ethos. The ethos is the context and purpose of the activity. It is as the expectation of consequence of an activity performed. It is the context where play is the subjunctive mood. The subjunctive mood observed in games and ritual are said to decontextualize the action and provide a suspension of rules, roles, and consequences found in ordinary life to allow for the exploration of new identities, rules, roles, actions, and social affiliations and status in a safe space.

Purpose of study

This interview was to inform design features to develop a program for pre-adolescent exercise with Dance Dance Revolution for the study of obesity reduction and increasing bone density. The study was also intended to get a sense of why a young woman sustained engagement with Dance Dance Revolution over three years to develop expertise, and how educators might replicate that kind of commitment to learning and practice.

Background of the study

Health care professionals have observed an increase in levels of childhood obesity. This increase has been attributed in large part to physical inactivity. Physical inactivity not only leads to obesity and poor cardiovascular health, it also has negative effects on bone health. Bones function to support a mechanical load (a force exerted by body weight, muscle, growth, or activity). Bone is constantly formed and reabsorbed throughout life in a generally balanced way. However, in a three- to four-year window during puberty, bone formation is accelerated. In that period, as much bone material is deposited as will be lost during a person’s entire adult life. During these pivotal years of bone development, physical activity is important for optimizing bone health, as it has been shown to reduce the incidence of fractures later in life.

Because it is difficult to motivate children to participate in the type of cardiovascular activities that adults engage in (running, cycling, aerobics), new strategies must be developed, and these may demand elements that            motivate the learner to sustain engagement over a longer period of time in order to promote and sustain life habits for physical conditioning.

Dance Dance Revolution is not your typical video game.

The video dance game Dance Dance Revolution may be a possible solution to increasing activity and mechanical load because of the amount of jumping activity, but the young person must be motivated to start, and engagement must be sustained for the activity to produce valid and reliable measures of obesity and bone density.

The issue under investigation is how to help young people start an activity and sustain it; the

simple answer to this was, seemingly, to make it fun; to make it a high-interest activity; but many toys, games, and activities are often tried once and then put aside. What came out of the interview was:

- the importance of aligning the outcomes with a desirable activity,

- the importance of group and environment to the construction of status and identity that makes belonging to a group desirable;

- allow for status and relation for reinforcement;

- the centrality of ritual and rites of passage in group performance,

- autonomy supporting environments,

- and again the importance of identity construction for transformation to instantiate sustained engagement conveyed through affiliation, apprenticeship, and expertise.

Interviewee/ informant

To explore this, we recruited Ellen as a DDR expert and possible employee to lead an after school program at one of our sites at the Minneapolis Public Schools. We had posted a hiring description for DDR experts and we had a number of responses; one respondent, Charles, shared that he had a lot of friends who were really good at DDR, and Ellen was listed as one of those people. Ellen came into the lab to show us her DDR play, and we were impressed with her expertise.

What was interesting about Ellen was that she was not from a subversive or reactionary sub-culture. Ellen is part of one of the least studied cultural sub-group in schools (Buckingham, 2007)—an urban, middle class teen that is successful in school, is respectful to teachers, has a part-time job, plays varsity soccer, traveling band, is part of the International Baccalaureate Program, and has a satisfying home life.

These elements of her identity were surprising. We usually assume that video game players are a disenfranchised fringe group at school who do not engage with the typical academic fare. But Ellen was able to balance not only her academics and music instruction, work a part-time job, but also play sports and have friendships. These elements of balance were enticing and we wanted to know how she was doing it so that we might try and replicate not only the physical health benefits in our bone density study, but also some of the psycho-social and affective elements necessary for sustaining engagement (Chapman 2006) —she seemed like a great role model for creating a curriculum that would rely heavily on identity development and she was an intriguing informant to help us understand how play identities might lead to work habits to form healthy minds and bodies.

Methodology and review of literature

The question driving this investigation is “why did she sustain engagement in learning?â€

According to Chapman (2006), engagement is more than behavioral time on task. When looking to measure growth or change, or even to understand whether a learner has truly engaged, an educator should also look for evidence of commitment and positive attitudes related to the activity and subject matter.

- Engagement is not just doing the work, it is a connection and an affinity to an activity supported from the affective domains (Chapman, 2003).

- Skinner & Belmont (1993, p.572) report that engaged learners show sustained behavioral involvement in learning activities accompanied by a positive emotional tone and select tasks at the border of their competencies, initiate action when given the opportunity, and exert intense effort and concentration.

- Pintrich and & De Groot (1990, in Chapman) see engagement as having observable cognitive components that can be seen or elicited through exploring the learner’s use of strategy, metacognition, and self-regulatory behavior to monitor and guide the learning processes.

These attributes do not magically appear in an activity because a student is told that it is good for them, and that they should commit to their betterment; Least likely is that they do it because we threaten, or because just because we want them to. A student must make a choice to commit to an activity and have that commitment reaffirmed over time to sustain engagement. True engagement in an activity is in some sense transformative and resembles identity construction, in that it changes who we are through cognitive, affective, and behavioral elements; but it seems likely that without positive reinforcement (Skinner, 1938) the behavior may result in extinction and the game becomes another resident on the island of misfit toys.

Dance Dance Revolution is considered a high interest activity for many young people, and it does have a reward system that gives real time feedback on performance with rewards for successful play; but without aligning those rewards and achievement with social capital, they lack meaning and status, and the reinforcement system remains a token economy (Ferster and Skinner, 1957) whose tokens are unredeemable. Since these flashing lights and high scores do not buy cars, cell phones and other tokens of esteem for young teens, it seems reasonable that gaining status and respect in a desirable community may provide the value that accompanies success and sustains engagement.

The work of Buckingham on identity development may provide some insight for connecting identity with purpose, motivation, and sustained engagement. Buckingham (2008, p. 3) states that:

Identity is developed by the individual, but it has to be recognized and

confirmed by others. Adolescence is also a period in which young people

negotiate their separation from their family, and develop independent

social competence (for example through participation in “cliquesâ€Â and

larger “crowds†of peers, who exert different kinds of influence).

Identity and status were traditionally conferred through rites of passage, and there may have been many culturally specific instances of these rites for different groups and related activities. Video games may represent a new wrinkle in the way that we enact and view rites of passage–games may offer a form of guided, ritualized behavior for identity construction and group affiliation as an autonomy supporting environment (Ryan & Deci, 1999), Affinity Group (Gee, 2001), or Community of Practice (Wenger, 1998).

A rite of passage does not need to resemble the tribal practices that led to vision quests, ritual markings, or exodus. A rite of passage may be organized in three forms: the process of separation, transition, and integration, (Van Gennep, 1960), but all three of these rites may also be presented as single rite (Barnard and Spencer, 1996). What is important for Van Gennep is the idea of Liminality, or the threshold. In the context of Liminality, the activity space may be far removed from reality, and roles, rules, tools, values, and status may be situated in the flux of play as if a hybrid or interstitial space (Turner, 1969). This concept of the threshold and liminality seems to validate Geertz (1972) and his description of the “Center Bet” in describing the ritual of Balinese Cockfighting and Benthams’ concept of Deep Play. According to Turner (1969), there may be many rites of passage in a person’s life through sub-cultural affiliation (Cock Fighting, DDR, First Job) where identity and entitlement are inculcated through desire to become a respected an acknowledged group member, where they can share in and contribute to group activity, participate in group spaces, and publicly perform renewing and furthering status.

Since identity is conferred from others, there are factors that can identify a person as a group member and as having identity markings. For Gee (2001), the activity is primary and provides the motivation, the source of group membership and markings; and this membership comes about from engagement in active communal practice that centers on the activity; the ancillary relationships stem from the interaction related to the activity. He states that these communities and spaces are hard to identify without knowing the person’s intentions — exactly why people are there. Whether a person actually claims group membership or is acknowledged can be difficult. For Gee, group membership may not be acknowledged or claimed, but attributes can still be observed. The role of Gee’s work is central to operationalizing identity and group membership through offering observable sociocultural markers that come from the semiotic domains as evidence of group membership.

A semiotic domain recruits one or more modalities (e.g., oral or written language,

images, equations, symbols, sounds, gestures, graphs, artifacts, and so forth) to

communicate distinctive types of messages. By the word “fluent†I mean that the

learner achieves some degree of mastery, not just rote knowledge. . . Semiotic

domains are, of course, human creations. As such, each and every one of them is

associated with a group of people who have differentially mastered the domain, but

who share norms, values, and knowledge about what constitutes degrees of mastery

in the domain and what sorts of people are, more or less, “insiders†or “outsidersâ€.

Such a group of people share a set of practices, a set of common goals or endeavors,

and a set of values and norms, however much each of the individuals in the group may

also have their own individual styles and goals, as well as other affiliations.

Gee (2001, pg. 2).

This work allows for certain attributes of group membership to be observable rather than subjective. A young person may have grown up participating in an activity with parents and young friends, but during the puberty years, may reject that affiliation based upon new goals for group membership. A new group may be more desirable than a current group, and the young person may cast of markings that identify them with the old group such as a hat from a uniform, ways of speaking, values, etc. This does not mean that markings of prior group membership with parents, family, and childhood affiliations are not still observable. For Gee it is the activities and the group practices that provide evidence of social learning and group membership from semiotic domains, and it is activity that is central to identity construction.

For Wenger, (1998) identity is central to human learning; identity construction and learning are distributed through community and relations; learning is socially constructed; and motivation is based on a desire for sharing and participatory culture. The work of Wenger shares many attributes with Gee’s work, but the focus for Wenger was on socially distributed cognition and learning as social participation. Earlier work explored the role of learning in apprenticeship, where newcomers would enter into a space where learning was situated and contextualized, and goals and purpose were evident due to entering the space. One entered the space to gain apprenticeship and attempt to acquire and learn the sociocultural practices of the community. Thus the individual is drawn to the group and begins to engage and learn by finding their role in a distributed, networked, cultural-cognitive process with the purpose of the individual as an active participant in the practices of a social community. This participation leads to the construction of his/her identity through these communities. From this understanding develops the concept of the community of practice: a group of individuals participating in communal activity– creating their shared identity through engaging in and contributing to the practices of their communities.

The difficulty with this theory is that group membership is hard to define. A person may want to be part of group and claim group membership, but not have the identifiable characteristics that define the membership, but it did lay the groundwork for many of the same features of Gee’s construct.

For Deci and Ryan (2008) these same attributes are also shared, but the focus of Self-Determination Theory comes from work on motivation with a focus on Autonomy — possibly built from early work by White (1959) where organisms have an innate need to experience competence, and experience joy and pleasure with the new behaviors when they assert competence over the environment.—what he called effectance motivation.

For Ryan and Deci motivation is based on the degree that an activity or value has been internalized, and this is based upon the degree to which the behavior has meaning within the context of the arena of performance. In this sense, the feelings of relatedness and belonging in a social, or group setting, play a part in the internalization process along with an inherent desire for competence and autonomy. In order to feel belonging and relatedness, an individual develops autonomy through competence and creates the identity for relatedness and belonging. This process can happen from belonging to competence to autonomy, or other sequences. The key motivating factor for Deci and Ryan is autonomy.

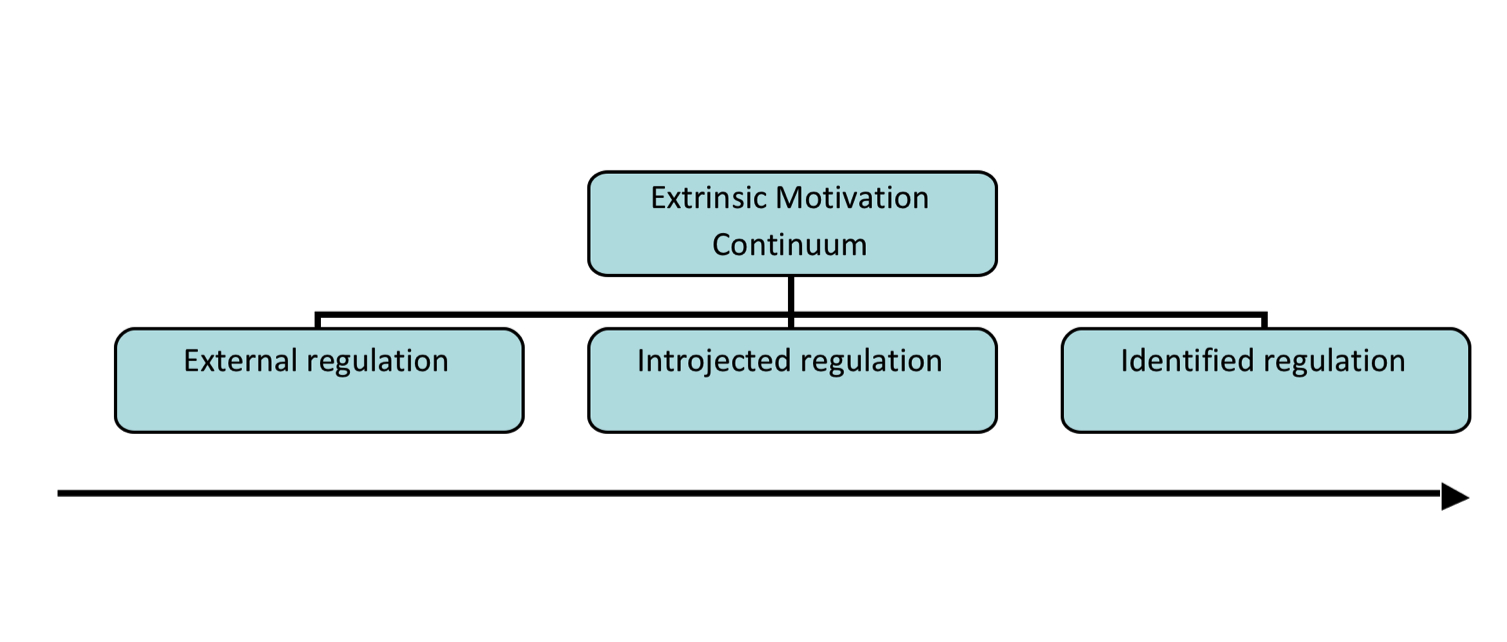

In order to sustain engagement for Deci and Ryan, motivation must be internalized . . . the external contingency must be “swallowed wholeâ€. By swallowed whole, the learner identifies the value of the new behavior with other values that are part of the self. This process of engagement is the transformation of an extrinsic motive, one that is reinforced from outside the learners’ values, into an activity that is assimilated and internalized by the learner as an intrinsic value that is part of their personal identity. This process involves constructing values aligned with the group and environment, and thus assimilates behavioral norms that were originally external as part of a new identity. Based on the degree of control exerted by external factors, levels of extrinsic motivation can be aligned along a continuum (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

- External regulation: doing something for the sake of achieving a reward or avoiding a punishment.

- Introjected regulation: partial internalization of extrinsic motives.

- Identified regulation: doing an activity because the individual identifies with the values and accepts it as his own.

Identified regulation is autonomous and not merely controlled by external factors. It is motivation for an activity that has been integrated as part of the learner’s values, and refers to identification with thvalues and meanings of the activity to the extent that it becomes fully internalized and autonomous (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Themes for coding

| Play

Subjunctive Mood |

Activity Space | Desirable social grouping |

| Ritual Rites of Passage | Belonging/ Relatedness | |

| Desirable Activity | Identified regulation | Apprenticeship |

| Affective commitment | Autonomy/ Competence | Cognitive theories of action |

Eleven themes from these theories of identity construction, ritual/ rites of passage, engagement, motivation, and social learning were taken in order to code the interview transcript to inform analysis and make decisions on what factors might be important for the construction our afterschool program so that we can track design efficacy and measure performance.

Data collection

The phenomenological interview methodology (van Manon, 200*) was used to try and elicit responses beyond descriptions of rationale to gather “thick descriptions” (Geertz, 1973) of affective, social, corporeal, and cognitive behaviors (which the researcher hoped for but did not expect) behind the activity and experience of playing Dance Dance Revolution (DDR), but also to encourage descriptions that were thick enough that the researcher might be able to identify instances of engagement situated and distributed learning across networks of time and space, mediated through shared activity, Â and perhaps to see if there were evidence indicating whether identity construction and choice did inform motivation and engagement.

Data Analysis

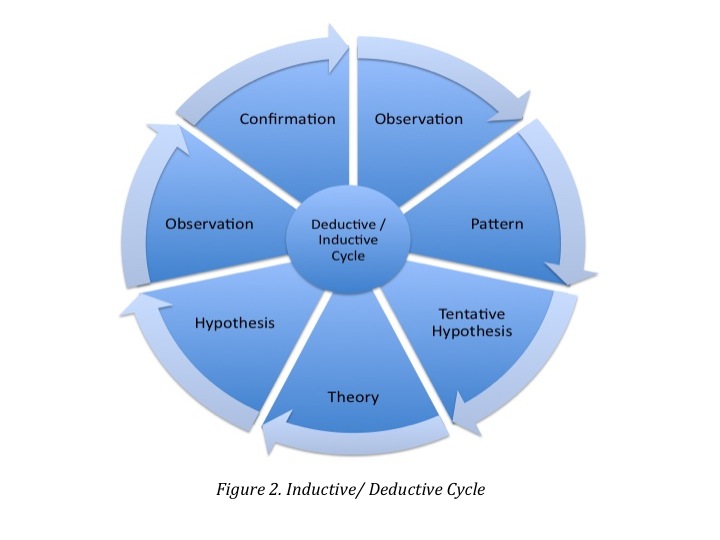

The critical discourse methods as espoused by Gee (1999) and Fairclough (2003) not only provide methodologies that are fundamental to qualitative analysis, but are also fundamental to the study of “the scaffolding of human affiliation within cultures and social groups and institutions,†Gee (1999, pg 1) and “how do existing societies provide people with the possibilities and resources for rich and fulfilling lives,†Fairclough (2003, pg 202). It was for this reason that these methods were used to explore and code the phenomenological interview transcript. Although a sample of one participant is not very robust for generalization, it provided a starting point for more focused theory testing, as well as to provide insights for ourselves as designers, and education practitioners.

Interview

This first excerpt from the interview begins to describe the motivation to learn to play Dance Dance Revolution. Ellen and I met on a nice spring day in the Whittier neighborhood near the Minneapolis Institute of Arts at a coffee shop called Spy House. When I had asked her what was the experience of playing DDR, she said:

The first time I ever played Dance Dance Revolution was with my

friends Tyler and Ben. They had it at Devon’s house and everyone

was playing this game. Really, I wanted to hang out with them, I

wanted to participate and so that’s when I started learning. Then it

was after playing with those guys for so long that I really started to

enjoy the game. I actually didn’t have a play station before that, so

I went out and bought a play station just so I could play DDR, yeah. . .

yeah, I didn’t want to be left out of it. Games are fun and I just wanted

to spend time with my friends and this is something that they were

all doing.

The basis for Ellen’s learning was to Belong to a Desirable Group. This idea of relatedness and Belonging were fundamental in her development of skills and collection of resources to develop as a player. However, she did not have the feeling of connectedness until she was really able to engage in the activity as a participating member —Autonomy/Competence. Also of interest was that the activity was not initially a Desirable Activity, “I wanted to participate and so that’s when I started learning”. After some time participating, she found enjoyment along with her sense of Belonging to a Desirable Group. This phenomenon suggests precedence of Belonging to a Desirable Group over Desirable Activity, and also suggests that an individual can develop interest in activity that might not have been initially motivating. Speculatively, there may be some indication for the importance of play as a subjunctive for developing affinity for an activity. It was clear that she had already identified with the people, but, based on the next excerpt, she had not identified or been identified with the activity.

I was excited because this was something I could participate in. I’ve played Halo and I’m not that good at it and everyone was starting out on this for the first time, so I thought I could be one of those good people at it and get respect from people. I was really excited. They have this huge TV at Devon’s house and everyone’s around you. I was kind of nervous too because you have to do this in front of people. Well, we were all kind of sitting on the couch watching the men and I was like I want to try it. I mean, some of them were interested in seeing me probably because they knew I never played before and they made me where I was probably going to fail, but then I actually really wanted to do it, so I was like I want to do it next! I thought I was going to be better at the game than I thought I was because I’m thinking oh these guys they don’t have any coordination. This’ll be easy for me. I’m kind of in shape, so I was thinking it would be pretty easy and then I do some of these songs and I was like oh, I need to go down a level! I thought I caught on fairly quickly.

What was clear from this passage was the importance of the activity and her feeling that she could be successful participating and “be one of those good people at it and get respect from people.” There are several parts to this that are especially interesting:

- Belief in her ability to succeed was essential in her willingness to perform publicly. Research on adolescents’ engagement in literacy for example has found that adolescent perceptions of their competence and ability to succeed may be a more important predictor of whether they will engage than their past performance. (Alvermann, 2001; Anderman et al., 2001; Bean, 2000; Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000). Studies of adolescents have also found that they prefer to perform where they know they will have success (Csikzhentmihaly, 200*).

- The fear of performing in front of the group with Autonomy/ Competence but that since people were just starting out, she might have a chance to be good at it and to be respected. Thismay have played an even larger role because she was one of the girls who watch, not one of “the men†who play the games and perform.

- The importance of the Activity Space and its affordances as well as the possible change in atmosphere with this new game, where there may have been more emphasis on Play as the Subjunctive Mood.

This makes a case for the importance of Affective Commitment, Competence as well as a Cognitive Theory of Action. Although these seem to be sublevels of Desirable Activity and Belong to a Desirable Group, that inform and reinforce action. She had created a Cognitive Theory of Action and knew that it was essential for her to perform to be acknowledged and claim membership — another indication of Chapman’s (2006) description of engagement and evidence of Identifiable Regulation. To claim Belonging to this Desirable Social Group, she realized whether implicitly or not, that she needed to participate through performance (Autonomy/Competence) to Belong. This supports Deci and Ryan’s position that Autonomy, Belonging, and Competence are basic needs that underlie motivation and engagement and satisfy Skinner and Belmont’s assertion of affective involvement.

In addition, Ellen had already aligned her values internally as Identifiable Regulation— but she had not found an opportunity with a Desirable Activity where she might have success in the Activity Space where she could feel confident that she would succeed and enjoy the activity,

“I could be one of those good people at it and get respect from people”

Halo and Counterstrike she described as work (Sutton-Smith, 1996), which has consequences for failure — the desirable group may have been much more advanced in their performance in Halo and Counterstrike, and perhaps took playing the game much more seriously and raised the stakes of the performance.

Games and play are often about choices without life-threatening consequences, but that does not mean that games are not taken seriously. They can be performance tests (Autonomy/ Competence) and Ritual/Rites of Passage that allow for the development and affirmation of a place within a group, establishment of pecking orders, and through this, community status and entitlement . . . and it is possible that the experience of being positioned to perform and possibly fail was some sort of initiation, a form of deep play (Bentham in Geertz, 1975).

This act of bettering oneself in public is a tricky situation—but it really must occur in public for a person to be seen as Competent/Autonomous and an acknowledged group member (Belonging). This Ritualistic phenomenon was described by Geertz as the “Center Bet†in “Deep Playâ€, (1975) and based upon Ellen’s description, it may be that as play in an activity advances, the play gets more serious and the stakes and status of the Ritual change, and the work ethos takes precedence over Play as Subjunctive Mood.

In the DDR trial, Ellen was tested to see how she would respond to public failure: she could have quit and gone home, or she could laugh it off and find the fun in learning and work towards acceptance. As will be shown in the next excerpt, Ellen found that there were others who were beginners that she could get better with, and more experienced players were actually helpful and willing (Apprenticeship) to teach — she also found that there is no substitute for experience, and that in order to become a part of the group, she had to go through the rites of practice and public initiation–according to Van Gennep (1960) this ritualized process is common to many societies where an individual passes from one stage of life to another, and it can involve separation from childhood environment, transition, and incorporation with new status. For Turner (1969), this game may not be as monumental as rites celebrating marriage or death, but still represents a moment of social transition and eventual change in status. The importance of this is the public acknowledgement of Competence, and this seems to be essential to identity construction and acceptance as a member of a group (Buckingham, 2007).

The performance/ initiation

Previously, Ellen may have wanted to be part of the group, but Ellen stated that the games they were playing did not provide her with much interest to play, even though she wanted to belong with the group and participate in their space. Because of this, she may not have been considered as part of the group, but maybe more of a tourist or poser; because belonging seemed contingent on being able to “doâ€.

I have a lot of friends who play Counterstrike and a lot of . . . almost every guy I know plays Halo. You can enjoy watching those games. I don’t enjoy it as much. Like I said, it’s just way more serious. They get more serious. Well, it’s like everyone is more quiet and focused, like they really get into trying to hunt these people down and kill them before they are hunted down and killed. DDR, you are playing against someone but then with Halo and Counterstrike you’re against all these people and you have to be like watching your back all the time. Even the people watching, they zone out and just watch it. For me it’s not as fun. As for DDR, it’s more like people jumping around and are less serious but it’s still a lot of fun.

Prior to Ellen’s embrace of the game, she was a groupie. She could talk about how Devon did, but not about her own experience. This came in part as being recognized as a player by her community, but it was also a confidence that came of public performance (Autonomy/ Competence) and embrace of public performance; sustaining engagement with the practice; working hard to develop status and identity related to the group and the activity and the freedoms and responsibilities that accompany them.

So what followed was me just trying to find where I could go to play. Then I kind

of got eventually frustrated with it—well, not frustrated but I wanted to play more,

so I decided to buy it for myself.

Yeah.

You play by yourself to get better to play with other people. I mean, it’s always fun to play by yourself and unlock new songs and things like that.

I got it for Christmas from my parents, so I didn’t have to buy it but I had to persuade them and make sure they got me what I wanted. They didn’t really understand but they felt okay about it because it wasn’t something violent or anything like that.

Then I was like look what I can do! They watched me. They thought it was kind of interesting. This was with my family on Christmas. Then my uncles and my little cousin who was maybe like seven, they all got really interested by it. So my fifty-year-old uncles are trying it and they’re getting really excited. My little cousin, she’s getting excited too. She doesn’t even really understand what’s happening on the screen but she’s like jumping around on the pad.

The need for Activity Spaces should not be underestimated, but it seemed clear that Ellen was ready and willing to share her activity in a space, her parents’ holiday party to get the game system, mats, and software.

Ellen’s playing the game with family coincides with the Ritual of Integration/Aggregation as described by Van Gennep (1960), where Ellen has returned to her family with a new status. This status may not rival her accomplishments in sports, band or academics in her family’s values, but in many ways it was a revealing of how she had become different – how she had created difference and separated and returned, and her family’s embrace of this new part of her identity — “gamer girl”.

Dance Dance Revolution, and other games played in Devon’s basement provided an experience that offered the separation and initiation for obtaining group identity through the ritual of public performance that could be recognized not only by the group, but also by others away from the basement and through this the identity and status are further reinforced through the rite of integration. It was through the activity that Ellen was conferred status and identity as member not only by her new friends, but through her family and the community that had the power to convey her status and acceptance. This conferred new identity and acceptance allowed her to become that gamer beyond her normal relations and to extend her community network and be recognized by others to develop new relations and status:

because we shared this thing, so it would be like oh so who’s house are we going to go to tonight to play DDR? Okay. Well, my friend Devon, his house was the main DDR house just because he had a great room for it and everything and his parents didn’t really care how much noise we made or how late we stayed there, so his house is generally the DDR house. Tyler, who was my friend prior, we would get together                  and practice a lot. Michael, he bought DDR around the time that I did and we were basically kind of on the same level and I got to know him better that way just by spending time with all these people. Nick, all these other guys, I had kind of known beforehand but now we spent all this time together. So it was basically we all met at Devon’s house and that’s what we would do for weekend after weekend after           weekend.

If we can draw from these Activity Spaces and domains and inspire the learner to feel a connection and affinity to traditional academic fare like engineering, literature, mathematics, etc. What is also evident that we can create Desirable Activities that align with academic learning where the learning outcomes are embedded in the activity, that supports committed participation and engagement.

What makes Devon’s house a desirable Activity Space was probably the Autonomy they were given in the basement. Devon’s parents gave them access to a big television, let them come and go, let them choose their hours, and allowed them to express themselves with their music played loud in activities of their choice. This was probably trust earned versus parental apathy judging from Ellen and her friends, but this kind of Autonomy cannot be underestimated. What seems to make an Activity Space desirable is the ability to have Autonomy/ Competence, and perhaps this is one of the factors that make for a Desirable Group and the desire for Belonging/Relatedness as well as in creating a Desirable Activity.

Although there seemed to be many homes the kids could have had their gatherings, none of them seemed very prominent in her description, and the only mention Ellen made in the interview of Activity Spaces other than Devon’s were her parents’ house on holiday, when she was showing new friends how to play that were not part of her DDR group at Devon’s; when she would practice to ready herself for Devon’s; and the hotel room on her band trip to New York City.

As Ellen’s ability with the game progressed, she was being recognized as DDR “gamer girlâ€, and this conferred a new identity and status. She began to find new connections throughout her school experience, as more people knew about her new status as a “gamer girl” beyond her former status as an International Baccalaureate student (Academic), varsity soccer player (Jock/Athlete), Band Member (Musician). It may have been important for Ellen to branch out and change people’s perceptions In the same way that she described the Desirable Group:

“Really, I wanted to hang out with them . . . games are fun.”

and the proposition that might follow as if a syllogism, is that:

gamers are fun, and I want to be fun too.

Perhaps all that work in Academics, Sports, and Band had made her appear too serious, and maybe she felt constrained by all of her commitments and wanted to break out to meet new, fun people? It is only conjecture and anecdotal, and she did not abandon her commitment to band, sports, or academics — she did graduate with an IB diploma — but as can be imagined, all that work in those areas may have made it important to find friends who had interests beyond her everyday world, and that being with them would allow her to step away from conversations about the team, assignments, practicing to perform, and set her apart.

Developing these relations more than fun, but a coping tool. The importance of play, according to Vygotsky (1972), is decontextualization, where an individual can gain gratification and pleasure even in the midst of unresolved issues and larger, time consuming projects. The role of pretense and imagination can bring about pleasure and in the face of uncontrollable circumstances; this can provide some relief. Perhaps the gaming provided an opportunity to decompress and laugh in the midst of all that responsibility and preparation. An example of this may be seen in Ellen’s bringing the game on a band trip.

Yeah, it was a school band trip. So a lot of us went and it turned out that a whole bunch of people knew what DDR was. It was interesting to see them play. Tyler and I, we kind of felt cool because our group that we had played with had progressed better than these other people that we were seeing play. They were like oh man this kid is so good and we play with him all the time. Tyler and I played against these                people— Yeah, we beat them pretty bad.

In this instance, the game activity did extend beyond the familiar Activity Spaces like Devon’s basement; it even seemed to provide an activity that she could share with new groups as a Desirable Activity that would make others see her as part of a Desirable Group that others would seek Belonging/ Relatedness. The game seems to have supplanted the importance of being part of the gamer group in Devon’s basement, and the activity became a means for extending her friend network as Gee (2001) as an Affinity Group, where people affiliate because of an affinity for an activity. The next section demonstrates this. As the activity began to change for the group members, relationships started to change, and the emphasis on the game diminished.

Well, a lot of the guys that I started playing it with, they moved on to other games because that’s what they do. They focus in on something for a really long time and then they’ll find something else will be just released and everybody else will just be playing that, so they’ll jump into that. Then there was always the people who have it, like Tyler and I, who will still play it. We didn’t get bored with it; it’s just then there    were other things. No. I don’t play it as much as I do anymore and my friendships through that have become different. I mean, we’re all still friends. DDR was just like this common thing that we had to like start us talking and then after that we talked about normal things. I became pretty good friends with a lot of people. I dated one of  the guys that I met for awhile. I don’t know, it wasn’t like any different than like you      meet people playing for a sports team. You have something in common and that’s what you’re coming together to do, and then you talk about other stuff because we’re not just focused on DDR. Well, at my work it’s kind of similar too. We’re all stuck working together and so then we get talking. Soccer and sports a lot. Any kind of group that you all come together and you have something to talk about and then we  just eventually expand on that and that’s how we became friends.

The DDR game did facilitate the relationship in ways that other games and activities did not, but in the end, the initial motivation may need to come from purpose only the individual can formulate. But play can facilitate this and may make the entrance to a group, the practice, and eventual mastery of knowledge, activity space, and activity more likely to be enticing and possibly provide for sustained engagement and eventual mastery. This makes a case for Play as a Subjunctive Mood.

Playgroups, and the activities that support them, provide a common ground for interaction. There is definitely a pecking order that comes from demonstrable competence and evidence of knowledge from the semiotic domains from the game. Games are built upon play, pretense, and decontextualization, but once these activities no longer provide pleasure and gratification, the activity may quickly end and the relationships and spaces that contextualize and support them may change in the way that Ellen’s DDR group cooled off: “and my friendships though have become different. I mean, we’re all still friends.

Games are structured forms of play, Dubbels (2008) that provide rules and roles that are defined to help members to decontextualize from the ordinary world where they have responsibility, deadlines, and environments they cannot control. These same rules and roles also help them know their status in the game, share common, spontaneous, and authentic experience without going too deep into personal motives, negative feelings, and Freudian meltdowns. Corsaro (1985) called this play group phenomenon the Actors Dilemma, and according to Corsaro, the Freudian meltdown, or oversharing, is one of the most common causes of playgroup breakup—perhaps play is the coping mechanism that allows for detachment and the ability to constructively work on what can be changed and separating from that which cannot be. Game roles may also allows for exploration of other peoples’ values and experience in a safe space without getting too deep or real, which represents an opportunity to try on and project different emotions, and build comfort and trust through common experience.

In terms of Ritual/ Rites of Passage, a game would be a means for rite of passage, where the Activity Space is no longer like the ordinary world, and rules and roles are different and even changed for the sake of experimentation and normal social and interpersonal boundaries can be tested without endangering status and relationships. With Play as the Subjunctive Mood, different parts of person can emerge and people can try on different personae without recrimination — because they are only playing.

Conclusion

In answering the original question, “why did she sustain engagement?†it became evident that her motivation to sustain engagement over time changed. She was attracted to the activity because she wanted to be friends with the kids who hung out at Devon’s basement — she wanted to be an acknowledged member of the group, not part of the fan club. To do this she had to perform and risk ridicule and a possible reduction in status. Geertz (1976) described this spatially in that the further away you were from the Center Bet, where the desirable activity takes place, the lower your status and importance to the main event and performers.

In order to be part of this group, she needed to perform, but she might was hesitant to try because of the games they were playing did not mesh with her sense of play and fun—perhaps because the play of these group members with these games (Halo, Counterstrike) was already too far advanced for them to tolerate a “newb” (new player) at the controller; and it might be better not impose oneself and risk ridicule or contempt if one is not contributing to the play, learning, and or status of the group.

The role of Play as a Subjunctive Mood in these Activity Spaces and Desirable Groups may be the organizing principle that makes these groups and activities desirable as part of identity construction, as well as the means for identity construction. The subjunctive mood situates and mediates the discourse around the group desirability, the space and possibilities for interaction, and the perceived activity and likelihood for success and may be the basis for initial motivation to engage and represent the one constant throughout Ellen’s experience with the game, group, and space. For a person to facilitate and construct an identity, they may need to play, just as children play doctors, firefighters, teachers, mothers, and even animals in games. It is through pretense that we are able to imagine and create cognitive theories of action and circumstance and it is through play that we develop this capacity. If we want to sustain engagement, we need to help students develop the capacity for Identified Regulation, where they may turn their play into meaningful performance when asked to perform in activities that begin to resemble rites of initiation and deep play. This process creates a subtle transition where the initial play activity becomes serious and is approached with the focus of work, like what Ellen experienced watching advanced players of Halo and Counterstrike, and eventually what she experienced in practicing between school, homework, and lessons to prepare for DDR at Devon’s.

What was desirable about this Desirable Group? Probably their reputations as gamers and their ability to talk as insiders about what they were doing in an Activity Space where they were given Autonomy and Competence; it may have been their ability to create spontaneous neutral experiences that they could talk about in the grind of school-band-sports-work, and how they could look forward to this Ritual space away from the ordinary, where Play was the Subjunctive Mood and replicate this feeling in difficult circumstances to separate from stress and worry.

This ability to detach and decontextualize can be a very valuable trait when dealing with pressures of studying for exams, working, and other responsibilities that cannot offer immediate gratification. This inability to decontextualize and detach is one of the central behaviors inherent in Play Deprivation (Brown, 1999). The original diagnosis in the 1960’s in describing the incredible violence of Charles Whitmore and his shooting spree from the bell tower at Texas A& M University. It was found that Whitmore was raised in very rigid environment where he was not allowed friends or play. He experienced a life that looked very successful on the surface. But in 1966 he committed what was the largest mass matter in the history of the USA. According to the National Institute for Play website (last visited 4/9/09, http://nifplay.org/whitman.html), Brown, who was a psychiatrist at Baylor College of Medicine at the time, collected behavioral data for a team of expert researchers appointed by the Texas governor to understand what led to Whitmore’s mass murder. What was found through interview, diary, and reconstructing Whitmore

had been under extreme, unrelenting, stress. After many unsuccessful

efforts to resolve the stress, he ultimately succumbed to a sense of

powerlessness;Â he felt no option was left other than the homicidal-suicidal

. . . Whitman had been raised in a tyrannical, abusive household. From

birth through age 18, Whitman’s natural playfulness had been systematically

and dramatically suppressed by an overbearing father. A lifelong lack of play

deprived him of opportunities to view life with optimism, test alternatives, or

learn the social skills that, as part of spontaneous play, prepare individuals to

cope with life stress. The committee concluded that lack of play was a key

factor in Whitman’s homicidal actions – if he had experienced regular moments

of spontaneous play during his life, they believed he would have developed the skill,

flexibility, and strength to cope with the stressful situations without violence.

Brown continued exploring Play Deprivation as a construct and found similar patterns in other violent offenders, and even traffic deaths related to aggression and chemical issues. The role of play cannot be underestimated for its ability to decontextualize and reframe experience. Play therapy currently is a treatment in child psychology for helping children talk about and understand forces beyond their control.

Play may be vital to our well-being. It has been said that the opposite of play is depression, and depression can lead to feelings of powerlessness — the opposite of what we saw in Ellen’s attempt at Autonomy/ Competence and her efforts to connect. In this way, Play as a Subjunctive Mood may perform an important function in the ability to adapt, perform under stress, and create flexibility and adaptation for dealing with seemingly impossible situations — play may offer way out, a way to cope. But play demands time and space– especially spontaneous play – an activity, as was mentioned, where often we see young people working out issues they have no control over (as in play therapy).

It seems that all three of the social learning theories are context dependent based upon the needs of the individual at the time. Ellen, she was attracted to a Desirable Group as in Communities of Practice (Wenger, 1998) because of the activities and space where this group interacted. And there may have been factors that led to her admiration of these boys . . . it may have come from her admiration of how these kids conducted themselves at school and their reputations that they were fun “gamers”; but it was not until there was a Desirable Activity (Gee, 2001) that she could participate; and participation in a public performance was necessary for her to be acknowledged and feel Belonging/Relatedness (Deci & Ryan, 2008). As the group changed their focus on activity, the relationships changed, and new relations were created through the activity; but eventually the activity diminished and new activities and groups presented themselves as desirable.

The utility of this analysis comes from these recalled phenomena as a pattern for planning instruction and understanding why people learn. We learn to become. We create and engage to gain new experience and entitlement and gain status without danger in our social network, as well as to learn from others, whether it is a workplace competency, gaining social skills, or as a means of adapting to stress.

Implications / lessons for designing instructional environments

This transcript from Ellen’s experience makes a case for developing instructional environments that allow for playful, autonomous group interaction structured as a game to allow for play in much the same way that ritual demands play.

This process of making work playful, or working hard at play, is in some ways like finding a vocation or calling . . . in some sense the performance as ritual play, as described by Schechner (1994), is not far off when it comes to identity construction. Identity is bestowed through communal rites of passage, where individuals are sent away, learn, and perform, and then return to be recognized with a new identity and set of responsibilities. They are judged and identified based upon their performance. This idea seems especially appropriate for adolescents, who are in the process of identity construction, and are trying to find out who they are through trying out new activities, people, places, attitudes, identities, and things in society that has so many rituals and groups, but none communally organized that focus new identities and vocations.

There is distrust for activities that resemble rituals, games, and play. Part of this may stem from the independence required of play; the time involved in the rituals and competency development, and our general distrust of play as adult activity. Wohlwend (2007) looked at this notion of work and play through showing teachers video of children in classroom activity centers. Although there were clear examples of what was taken to be off-task behavior (Play), she found that teachers were able to find value in their students play if they were generative in creating connections and transfer to the students’ process and linking it to academic discourse.

The trouble with the perceptions of practitioners and policy makers seems to arise in the misperception between what Sutton-Smith (1997) called the Ethos of Work and Play. Given the opportunity, we may find that Play is a reasonable portal to motivation and sustained engagement through linking to the deeper learning that comes from identity construction and these oddly transformative communities that rise up out of them. In many ways, activities in formal and informal learning environments may not mesh with the intended identity of the learner, and this may indicate the difference between education and socialization along the lines of hegemony. The learner may choose a group affiliation antithetical to the purpose of the classroom.

So how might an educator integrate play, games, and lessons from these social learning theories?

I have used these principles on several occasions to explore games and play as effective methods for aligning content and process with resistant and reluctant learners.

Principle 1 — Play as a Subjunctive Mode

Engineering can be a very fun class, but the curriculum I was supposed to teach was very un-fun. In fact the curriculum was the source of the dysfunction. I was being asked to start class by presenting standards, why the standards were important, and tell the students why they were learning what they were learning. I found that this was much more for the benefit of observers evaluating the quality of my teaching than it was to motivate and engage the students.

I still use standards, and I still feel it is important to share the larger scheme of things behind activities and what they might be preparing for, but I do it with Play as the Subjunctive Mood. The first thing I did was to quit thinking these kids would commit to a curriculum where they were asked to redesign a coffee mug as an activity to learn engineering principles, fulfill standards and a rubric on a power point that came with the packaged curriculum. Fear of failure was not a big deal. Many of them were accustomed to it. They had checked out as an act of integrity and in doing so had found that they could dictate terms to teachers because of their disruptive behavior. Although my departure from redefining coffee mugs and the “do it or fail†curriculum did not sit well with the administrators, it did result in engagement from my students.

I told them that we were going to be having a boat race, and that I would be bringing in my wading pool from home, and that we would be making sail boats out of Styrofoam to race across the pool. I structured all of the engineering principles so that they were embodied in the task, and that through experience, we could discover them. What was essential in this case was not in joining a desirable group, but in participating in a desirable activity where their group could interact in the activity space semi-independently, and that the task was one where they believed that they would have early and instant success.

In addition to this, I also tried an experiment where I used a different approach to creation of subjunctive mood:

Work — I told the kids that we were really behind and that we would have to work hard and be rigorous in our approach to these boats. That it was incumbent upon us to learn terms like resistance, surface area, momentum, and force and apply them into our hull designs. What came from this my disappearance from their radar. I was talking, but they were ignoring me, tuning me out. When I asked them what they were supposed to do, many of them did not know, and many of them defaulted to resistant behavior.

Play — I told the class that we had a fun activity where we were going to be building boats and that we were going to have four kinds of races: speed, weight bearing, stability, and general purpose. I told them that I was going to be showing them examples of boat hulls and that they should play with them a bit to decide what style of boat they were going to make for the races they were going to participate in. I found that kids had listened, knew what to do, and really wanted to start. All of the same principles and terms were still present in the unit, but they now had permission to be playful and perhaps fail. Play implies failure recovery and experimentation. Many of the kids made crazy boats that would never work, but they were fairly successful in using the terms to justify their design for each race. It is not always what you do, or whom you do it with – it is how you do it.

Principle 2 — Desirable Groups

The role of Desirable Groups was primary for Ellen as a motivator for her becoming a DDR expert, but the tricky part about Desirable Groups was that underneath it was the issue of Play as Subjunctive Mood. A person may be attracted to a group for a number of reasons as we noticed from the three social learning theories. The grouping provides basic needs as in Self-Determination Theory; it provides apprenticeship and acknowledgement (Lave, 1998); and it may be ancillary, as in the attraction to participate with others in an activity. A Desirable Group can be a great motivator, but what was found was that eventually the Desirable Activity gets old and people move on and the group affiliation was not all that was necessary for sustaining engagement. This could be because the aspirant group member now understands what is behind Cool Kids Curtain Number One and the mystery of the cool kids is solved; or because the lesson from the apprenticeship has been assimilated. Whatever the motivation, indications were that she did join the group to learn who they were and why they were cool, and that after the fun with the activity wore out, the friendships drifted apart and they moved on to new activities. In addition, that the activity was used to branch out and connect with new groups.

With this in mind, we can situate and structure relations, change communication and status dynamics with Desirable Activities that are well-structured through Activity Spaces that have entitlement and opportunity. In thinking through some of the most well-constructed methods for creating cooperative groups, Cooperative Learning depends heavily on structuring Positive Interdependence (Deutsch, 1962, Johnson & Johnson, 1989) of the sort all three theories seek to describe, as well as construct through what was described from Play Group Literature (Corsaro, 19**) as spontaneous neutral experience, where people could build trust and common purpose.–where to succeed, everyone must succeed.(Johnson and Jonson, 2008, http://www.co-operation.org/pages/cl.html#interdependence).

The key element of groups seems to be status and what a person must do to get it. The danger of the Center Bet and the amount of support that comes with affiliation might be the deciding factor – Perceived Ability to Succeed—but it seems more likely that creating an atmosphere with Play as the Subjunctive Mood may be the best predictor of Group Desirability—which seems to come from status, space, activity, likelihood of success and acknowledgement.

Principle three — Spaces

Spaces are where we offer autonomy, equity, entitlement, objects, atmosphere, interaction, and relationships. By creating spaces where learners can self-govern to an extent, we make them desirable, especially if there are desirable tools and resources as affordances. What I did with the boat unit was to create a rite of passage to get from one learning space to another. An initiation where students had to perform to move to the next room — to make that desirable, I put the tools and materials there and gave the students (trustworthy students always get there first because they listen and finish the work early) and allowed them the autonomy to start and work with autonomy and privilege.

The students were told that in order to use the tools and start on their hull designs, that they had to use the hull examples and sketch a hull design In their engineering notebook, and then explain why and how the hull would perform well in specific race conditions (speed, weight-bearing, stability, general purpose) using the key vocabulary postered on the wall. When they were able to describe why and how their hull would perform well, they could go and begin building. This separation from one room to another was where I was able to coach, counsel, and cajole students into thinking more deeply about their designs, make suggestions, and enter their grades. All roads went through me as the Center Bet.

Principal four — Desirable Activities

One of the key issues in creating sustained engagement and identified regulation is in creating activities that align with the goals and purposes of the learner, or exposing the learner to something they think is really cool and they want to do. Making boats was not what many teens would consider a “cool” activity, but it did hold attraction for them when I showed them the tools, the materials, and gave a brief overview of what they would have to do. Getting kids to engage may just be a matter of creating some fun, and showing that they can have early and instant success; and, that they can make adjustments if they make mistakes. There must be time allowed to go deeply into learning to allow for the student to commit to expression in the work – the work has a part of them in it.

That will allow them to create a cognitive theory of the activity, and also allow for a belief in their future success. Add to this the opportunity to work cooperatively and learn from the work of other class members — some call this copying, I call it modeling and apprenticeship — then they can make a start (often full of errors and mistakes!) and adjust for excellence as they work with others and begin to better understand the project/activity. In this way we enable the spontaneous neutral experience that can be useful for beginning the learning process and also building relationships/ belonging, and autonomy and competence through the activity.

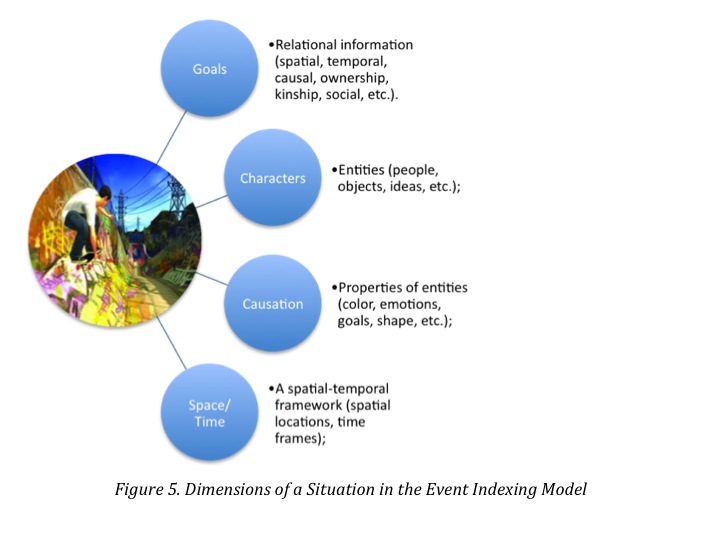

The key to this principle is in embedding the learning in the activity so that learners can discover the learning principles in the process of the activity through performance and reflection, where they compare what they have done with the work of others, and the instructor can provide encouragement to scaffold further development. Oddly, this is how scientific principles often presented in the textbooks were discovered before they were in the textbooks for memorization– they were tripped over by the scientists and then operationalized into methodology that some memorize as students, and others are lucky enough to rediscover in class. This can be done when we think of instruction as games and learning as structured forms of play. Some important elements for designing instruction as play are offered in this taxonomy of play for instructional design:

- Cognitive Theories of Action: we capture the imagination and build cognitive theories of action through imagery/ visualization (mental modeling).

- A key word for the instruction should be “IMAGINEâ€.

This first category in the taxonomy provides a basis for testing comprehension. It is important to be able to create mental model and theory of the action. The key attributes are visualization and imaginatively creating mental models and segmenting process and attributes for indexing in memory. If learners index and visualize well, they will likely have fine grain memory of the experience to draw upon for future use. So creating these mental images is very important for creating the motivation to engage, belief in future success, and a cognitive theory of action.

- Roles: provide roles and identities they can try on and play with, and offer the ability to change roles and play with the identities.

- A key word for instruction should be “IMITATEâ€

Working with others:Â A great draw because it allows for interaction. Many students need to be able to copy other students until they are able to IMAGINE and create a cognitive theory of action. Some learners do not learn well from instructors. They need to watch another learner translate the experience. Trough this, they not only learn how to start the assignment, but also how to create a cognitive theory of action on which they can improvise and express themselves through and commit to the activity. I cannot tell you how many times I have seen resistant learners get into a groove and not want to stop the project once they finally get started!

- Roles: In the case of the boat project, they became Naval Architects and Marine Engineers; just learning about what these folks do as a profession, and, that these professions exist opened a lot of high school eyes and creates schema for the semiotic domains of each role. They also had Learning and Functional roles – see Appendix B.

- Structuring group work: The creation of roles in cooperative learning as Johnson and Johnson suggest (200*) is very powerful and also what we see in early childhood play, as well as more advanced game experience for video games, teaching empathy, and modeling interaction for professional development. In structuring the work through roles, each group member has role specific tasks. Play Return to Castle Wolfenstein or look at game specific roles (character classes) in Appendix A, and imagine how these roles would culminate in teamwork for a mission. Each character class has several unique abilities and these come with different learning roles and functional roles.

- Rules — aka, the Identity Tool Box — Provide rules, values, language, actions, and tools associated with the roles and identities (semiotic domains) that they can work with and act upon that are inherent to the task, where the performance is the assessment. The role of the Naval Architect is to design a marine vessel for specific activities. The elements that define this role are the tools, activities, language, values, and outcomes associated with the role, and ultimately, the boat floats or it doesn’t. This embodiment is informative assessment, where the action provides immediate feedback through complete or partial mastery, or failure and the role provides for measure of progress and schema development based upon knowledge of the semiotic domains.

- Branching — Create choices and branching decision networks — and it is important here that the learners explain their cognitive theories of action and are asked to utilize and explain the identity tool box to support their choices and why they did what they did, and what might be next.

- Contingency/ Probability — this comes about when we consider the possible contingencies that might come from an action through prediction and hypothesis testing. Examples of this are resource management; awareness of likelihood of an action based upon knowledge of the game/ instructional environment, and attempted quantification and probability of failure/ success.

This structure for instructional design is a variation of A Taxonomy for Play from Dubbels (2008) and has been the basis for a number of successful curriculum units as well as digital games and is also available at www.vgalt.com.

A final note ~ Play as Subjunctive Mood

A brief experiment testing this occurred at Games Learning Society in a session called Real Time Research, where groups of participants from the RTR session went into the conference and conducted research on games. The author created a tool for measuring engagement to test whether Play as a Subjunctive Mood, or Work as a Subjunctive Mood would yield the greatest engagement from GLS conference participants. The hypothesis we were seeking to test was whether talk about play would elicit greater engagement on social, affective, and cognitive levels as compared to work.

The hypothesis was that people would engage with their descriptions differently when talking about work and play, and the sock puppet would elicit play behaviors and greater engagement. This would be gauged through analysis of the discourse captured in the video recordings of the interviews and then coded with a framework built from elements of engagement as summarized by Chapman (2003) and codified (see Appendix C).

The interviewees really engaged and took risks with the sock puppets. What is compelling about this experiment was that we were able to elicit more of the person with the sock puppet than we were with simple talk—there was much greater engagement and the participants seemed to enjoy the experience. The changes in treatments through creating different subjunctive mood –play versus work—were really quite dramatic.

What is important about these observations, as well as the finding of the analysis of Ellen’s experience with Dance Dance Revolution seems to be the expectations about interaction and purpose: Play as the Subjunctive Mood seems to represent a portal to engagement and its sustenance.

Appendix A

From the Wikipedia:

Soldier: The soldier is the only class that can use heavy weapons. They are: mortar, portable machine gun (MG42), flamethrower, and bazooka/Panzerfaust. On the No-Quarter mod the Venom machine-gun and the BAR (Allies) or StG44 (Axis) have been added as well. Leveling up gives the Soldier benefits such as the ability to run with heavy weapons (instead of being slowed down).

Medic: The medic has the unique ability to drop health packs, as well as revive fallen players with a syringe. They also regenerate health at a constant rate, and have a higher base health than any other class, which makes them the most common class for close-in combat. When a player has achieved skill level 4 in medic, they get Self Adrenaline, which enables them to sprint for, longer and take less damage for a certain amount of time. Some of the medics act as Rambo Medics. Their emphasis is on killing rather than healing or reviving.

Engineer: The engineer is the only class which comes equipped with pliers, which can be used to repair vehicles, to arm/defuse (dynamite or land mines), or to construct (command posts, machine-gun nests, and barriers). As most missions require some amount of construction and/or blowing up of the enemy’s construction to win the objective, and as defusing dynamite can be very useful, engineers are often invaluable, and one of the most commonly chosen classes. The engineer is also the only class capable of using rifle muzzle grenades.

Field ops: The field ops is a support class which has the ability to drop ammo packs for other players, as well as call air strikes (by throwing a colored smoke-grenade at the target) and artillery strikes (by looking through the binoculars and choosing where they want the artillery support fired). This class has low initial health, but makes up for having an unlimited supply of ammunition.

Covert ops: The covert ops is the only class which can use the scoped FG42 automatic rifle, the silenced Sten submachine gun (or MP-34 on some Mods), and a silenced, scoped rifle (M1 Garand for Allies, K43 Mauser for Axis). The covert ops has the ability to wear a fallen enemy soldier’s clothes to go about disguised, throw smoke-grenades to reduce visibility temporarily, and place and remotely detonate explosive satchels. By looking through a pair of binoculars, the covert ops can spot enemy landmines, bringing them up on their team-map. The covert ops also shows enemy soldiers on the team-map. Medic, Engineer,  This creates a fluid transition to the next category.

Appendix B

Functional Roles – Adopted from http://www.myread.org/organisation.htm (last visited 3/9/09)

ENCOURAGER and COP

- Reads instructions and directs participation

- Read the instructions

- Call for speakers

- Organize turn-taking

- Call for votes

- Count votes

- State agreed position

ENCOURAGER and SPY

- Summarizes findings and trades

ideas with other groups

- Check up on other groups

- Trade ideas with other groups

*Allowed to leave your place when directed by the teacher

ENCOURAGER and SCRIBE

- Writes and reports groups ideas;

is not a gatekeeper.

- Record all ideas

- Don’t block

- Seek clarification

ENCOURAGER and STORE KEEPER

Locates, collects and distributes resources including informational resources like web pages and encyclopedia entries

- Get all the materials for the entire group

- Collect worksheets from the teacher

- Sharpen pencils

- Tidy up

*Allowed to leave your place without teacher permission

LEARNING ROLE for LITERACY–

Freebody (1992) and Freebody and Luke (1990) identify the roles literate people take on.

CODE BREAKER

How do I crack this code?

· What words are interesting, difficult or tricky? How did you work them out?

· What words have unusual spelling?

· What words have the same sound or letter pattern or number of syllables?

· What words have the same base word or prefix or suffix?

· What words mean the same (synonyms)?

· What smaller word can you find in this word to help you work it out?

· What words are tricky to pronounce?

· How is this word used in this context?

· What different reading strategies did you use to decode this text?

· Are the pictures close ups, mid or long shots?