The work I have done surrounding games has led to improvement in reading scores. In 2006-2007, I took over the Language Arts Instruction for an entire middle school in Minneapolis, MN. The students were primarily drawn from North Minneapolis, qualified for free and reduced lunch, and were very bright, but were not scoring well on the standardized assessments. I implemented a curriculum that studied video games as new forms of narrative. Games tell stories, just like the anthologies stacked on my shelves. The difference was that when I pulled out the anthologies, classroom management became more challenging, as most of the kids were willing to get a behavioral referral than sit through a reading of “The Treasure of Lemon Brown” from the anthology.

The work I have done surrounding games has led to improvement in reading scores. In 2006-2007, I took over the Language Arts Instruction for an entire middle school in Minneapolis, MN. The students were primarily drawn from North Minneapolis, qualified for free and reduced lunch, and were very bright, but were not scoring well on the standardized assessments. I implemented a curriculum that studied video games as new forms of narrative. Games tell stories, just like the anthologies stacked on my shelves. The difference was that when I pulled out the anthologies, classroom management became more challenging, as most of the kids were willing to get a behavioral referral than sit through a reading of “The Treasure of Lemon Brown” from the anthology.

These referrals were a lot of work, and there is no academic learning happening during that process.

I decided that instead of pushing stories at them, I should ask them what kind of media they liked. Most of them told me that they played video games and liked television, but few if any had any idea that there was anything of value in games besides entertainment. My role was to get them to understand literary elements, genre patterns, and critical thinking–the things being tested in the new standardized tests! The games provided an easy entry into narrative fiction, with the opportunity to also discuss genre and film techniques, as well as interaction and games studies.

Often people assume that kids are naturally good at games. That because they are young, that children are digital natives, and can comprehend and problem solves like secret genius in the wilds away from the classroom. Surprisingly, most kids are not fluent in how games work, they struggle with in-game problem solving, and they are often limited in discussing how games work. Surprised? One would have thought there would be an easy transfer of learning from games to books. But it was just not so.

There was no hidden genius here–many of the kids knew all about games, but few actually played them. Is this a digital native? When we use that term, we assume that these kids have great knowledge and critical thinking skills because of video games and television, and if we could only tap into them, they would show us the expertise we hoped was there with digital media, where they lacked with printed text. This was also found in a previous study.

Disappointing as that can be, games do offer a high interest, and more accessible narrative. I decided to use this opportunity to use their interest in games to develop their potential genius in books. Games provide interaction, social capital, and complex situations that kids can describe when taught to compose walkthroughs and multimedia book reports. The video games are actually were more accessible to kids: they have the same literary patterns, but the kids don’t have to take the step of decoding the words. This means we can practice literary elements with more accessible text. And I don’t mean infantilized “readability” accessible. I mean that the students were interacting with age appropriate, high interest, complex stories, and getting feedback as part of the game play. They could play and discuss, and build their awareness of the story, just like we do with reading circles.

The intent was to study games like we would study a printed text. Many of the students were game players, but few were very successful game players. This 9 week unit was well-received, as many of the students were interested in learning more about games, getting better at them, and doing something we did not ordinarily get to do in a classroom.

The difficulty that I was facing came from cultural beliefs about games. Many believe that games are devoid of learning and academic uses. This was especially true for many of my colleagues. They had the feeling that kids were just participating with weapons of mass distraction, and there would be a debt to pay on the upcoming state MCA2 reading test. For this reason, I made sure I educated my administrators, Milken TAP observers, and parents after I had done my planning. I made sue to invite stakeholders in to my room to observe, evaluate my instruction, and to interview kids and make them justify the unit by asking them direct questions about the value of studying games at school.

The kids did defend the unit, and made sure to back up what they were saying with examples. One student, Tony, when asked what value there was in studying Sonic the Hedghog replied, “you don’t understand, Sonic is just like the Odyssey story, he just wants to get home.”

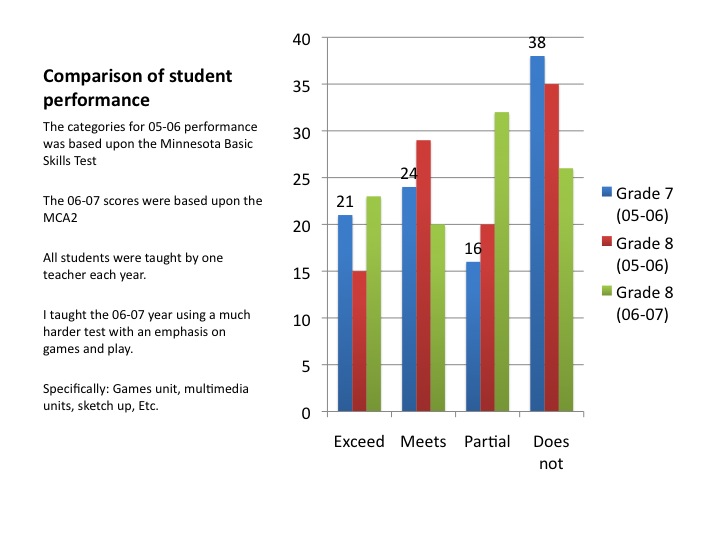

Because a large percentage (38%) of my students were not even close to passing the Minnesota Basic Skills Test, I was questioned about the usefulness of this unit when I should be doing reading drill and practice. However, my administrators thought I had an innovative idea, and parents supported this unit.

So 38% of my eighth-graders had a cut score of 1 on the Minnesota Basic Skills Test (MBST) — a test based upon recall– and we were about to face the Minnesota Comprehension Assessment 2 (MCA2), which is a comprehension assessment based upon genre patterns and literary elements. The standards for reading and literature asked for the students to understand plot, setting, theme, etc. This is not a recall test.

My kids were all bright, but they had disengaged from the testing process, and the preparation for it. Saying something would be on the test was not motivating, but comparing a game title they looked to other texts we read was motivating. Now we were getting the practice necessary for identifying the kind of conceptual information necessary to do well on the MCA2: they began learning literary elements and genre patterns.

I created this curriculum of game study. The organizing principle was that games are new forms of narrative, and that by studying game narratives, I could teach them literary elements and genre patterns. I created rubrics and assignments from the literary elements from the Minnesota state standards and integrated ideas from traditional Language Arts curriculum.

This is what happened:

You will notice that between Seventh grade (Blue) and the Eighth grade the following year (Green) there was significant improvement. During that eighth grade year, we had better scores on a harder test. In a year when we switched from the Minnesota Basic Skills Test to the Minnesota Comprehension Assessment to the MCA2, we had significant improvement across the cut scores.

What you see in comparing my eighth-graders (GREEN–took the harder MCA2) with the eighth-graders the year before (RED — took the MBS) was that there was a significant difference in achievement differences in the bottom performers. There were significantly fewer in the bottom cut score: a 9% movement out of “Does Not Meet”.

When comparing tmy students 05-06 seventh-grade students their scores as eighth-graders, there was a 12% improvement.

Not only was there improved test performance, but I was seeing my students return to school, and showing improved performance in the classroom, and on the test. The return of these kids was very satisfying and I had fun teaching the unit. What was great was the change in the learning culture. The kids really valued the time we spent and professed that they were learning. But it was also satisfying to see an increase in the amount of students who met or exceeded the higher standard.

The unit was not easy, but the students had something interesting and more concrete to apply the concepts I want them to learn. Remember, I built my games unit on the standards. Games are another narrative. They have all the same literary elements and genre patterns. My students were basically doing a technical writing assignment in the form of a multimedia book report.

The bottom line, they surpassed expectations on the more difficult MCA2 test. We were expected to go down 12%. We went completely the other way.

We did do complementary readings, like The Odyssey, Raisin in the Sun, Sonny’s Blues, Langston Hughes, and more. The key element was that the kids now had a portal into these other areas. The video games unit gave them success, and showed them they could do it. A big part of this was the creation of meaningful rubrics, and my taking a role as facilitator rather than know-it-all. I could ask, I could use the language of the rubrics like roadmaps for assessments.

But the learning did not stop there. The kids opened to the learning,and the became willing to open the books. And I know it worked. We were taken on a field trip to the Guthrie Theater, and on our tour, we were taken under the stage. The docent told us that where we were under the stage was called “the underworld”. The kids ALL looked at me, and said, “is this why you brought us here? Just like in the Odyssey?”

I said, “of course, yeah!” not having any idea, and we laughed.

We had practiced using the abstract concepts like literary elements and genre patterns with more accessible narratives (games), and applied what we learned about game studies to talk about literature. We used game studies to leverage printed text. Stanovich calls this compensation–warming up cognitive cold spots with warm ones.

This unit valorized activities that kids choose and participate in outside of school. It created a situation where kids who were often not high achievers, but were smart and understood the games, could now take leadership, and use their prior knowledge and experience with games, and help classmates. This was a win-win for developing academic skills, and life skills.

Central to the student’s success was that the instruction and assessment were grounded with an empirical model of reading comprehension, which viewed comprehension as the construction of mental representation. The better kids are at creating mental representation, the better they will be at questions and problem solving.

Once students can visualize and create mental representation, the can reflect upon the story and begin to apply the literary concepts and genre patterns. This was easier with games because they did not have to learn from a text, and get to the content through decoding symbols into meaning. When they payed a game, they saw and experienced, and could conceptualize from what Piaget called Image Schemas–mental representations from the senses, and learn the characteristics of the literary terms in the context of the things they were abstracted from.

What many kids who struggle with reading face is not cognitive deficits, but a poverty of experience, and thus experience with the world to attach to the words and concepts we want them to learn. If you don’t know about music, reading about it will not give you a personal, or deep understanding. You may understand in theory, by learning one abstraction by connecting it to another–but this is wholly different than having experience to develop concepts through induction, rather than deduction.

But that is often what we do in the classroom. Present the abstract concept, and ask them to learn in by reading–another abstract process dependent upon decoding and translating symbols into mental images. This seems backwards. Imagine a child who has never seen a peach, or known anything about peaches trying to decode, “he lifted the peach to his mouth and was surprised to be tickled as he took a bite.”

Without prior knowledge and experience, the child cannot know about peach fur. Would you imagine arms and tickling fingers?

Games and objects ground instruction, and provide the basis for experience and mental representation — comprehension. When we have this, we can spend less time decoding and more time discussing printed text. So by writing about accessible narratives such as games, we were more successful when reading related printed text. We had learned process, concepts, and deconstructing problems. This led to huge changes in student academic performance and confidence.

The majority of my curriculum that year was in studying video games as new narratives.

Here is the curriculum

Here is a story about what we were doing

Here is a class you can take I have been offering for the last seven years. You can take it online here at Professional Learning Board.

There is a lot to learn in a game, but there is a whole lot more to learn outside of the game in documenting, listening, presenting ideas, and extending them, than just playing the games themselves.

If you want, there is a whole bunch of games curriculum on my teaching blog for language arts, reading, engineering, computer science, etc.

Everything from board games to curriculum for analysis of a time line. You might notice that they are set up to be run like a game.

I am hoping that this article makes a start for teachers embracing a model where they consider Learning by Design.Interestingly, games are also involved in assessment, and kids like to know their scores. The scores are an indication of learning.

And the learning is the fun part, the content and the problems are hard and learning is not always easy, but it can be desirable. Games are hard too, oddly enough, but when enough kids play them, and it creates enough buzz as social capital, there will be interest and some sacrifice to try and persevere in learning.

Tenacity, and metacognition are learned traits. With games and play, we can teach them.