This is a very long post.

What do we need to talk about?

- Memory is unreliable and we can and do make it up as we go.

- Because of this we can help people who have been in great trauma . . . We can also worry about how this might otherwise be used.

- When we talk about memory and moral decision making, it is important that we have community that reinforces dialog and other perspectives.

- How this relates to schools and education

- Community takes time, patience, openness, dedicated space, and a willingness to move beyond the superficial– a willingness to understand before one seeks to be understood.

- Popular culture can be easily dismissed, as well as the young people who participate in it, but we are missing out on a chance to broaden and deepen and share our values when we withdraw and demonize.

- These all lead to your task to inductively form a view.

- You will find mine at the end.

So here we go.

What if games, or even a drug can change your memory of a situation?

With games, or virtual reality in this post, they are used with a qualified physician to treat PTSD, but many kids play games and participate in violent media with no oversight.

But first things first, games can be used for relief of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

According to the DSM IV:

“Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (DSM-4) is caused by traumatic events that are outside the range of usual human experiences such as military combat, violent personal assault, being kidnapped or taken hostage, terrorist attack, torture, incarceration as a prisoner of war, natural or man-made disasters, automobile accidents, or being diagnosed with a life-threatening illness.

According to the NIMH (National Institutes on Mental Health), PTSD is an anxiety disorder that can develop after exposure to a terrifying event or ordeal in which grave physical harm occurred or was threatened. Traumatic events that may trigger PTSD include violent personal assaults, natural or human-caused disasters, accidents, or military combat. More about PTSD »

Signs & Symptoms

People with PTSD have persistent frightening thoughts and memories of their ordeal and feel emotionally numb, especially with people they were once close to. They may experience sleep problems, feel detached or numb, or be easily startled. More about Signs & Symptoms »

Oddly, many, and I might say a lot of, video games have violent content where you are directly in the fray–that is if you have suspended disbelief, and really begun to invest cognitive and affective focus into the game and the outcomes.

Maybe it is ironical– yes I did say ironical and spell check said it was a word–that games can be used in this way.

Can games MAKE UP OUR MINDS?

Games have been used for phobias and other psychological treatments like arachnophobia and there are papers on this if you search. Here is one.

Memory is plastic and malleable like silly putty,

and oddly silly putty is the same color as your brain.

The idea that we slowly reacquaint and work through the trauma makes a bit of sense with some of the research that has been going on since Loftus investigated false memories. In a classic 1978 study led by Elizabeth Loftus, a psychologist then at the University of Washington, researchers showed college students a series of color photographs depicting an accident in which a red Datsun car knocks down a pedestrian in a crosswalk. The students answered various questions, some of which were intentionally misleading. For instance, even though the photographs had shown the Datsun at a stop sign, the researchers asked some of the students, “Did another car pass the red Datsun while it was stopped at the yield sign?â€

Later the researchers asked all the students what they had seen—a stop sign or yield sign? Students who’d been asked a misleading question were more likely to give an incorrect answer than the other students.

Later the researchers asked all the students what they had seen—a stop sign or yield sign? Students who’d been asked a misleading question were more likely to give an incorrect answer than the other students.

One of the scientists who has done the most to illuminate the way memory works on the microscopic scale is Eric Kandel, a neuroscientist at Columbia University in New York City. In five decades of research, Kandel has shown how short-term memories—those lasting a few minutes—involve relatively quick and simple chemical changes to the synapse that make it work more efficiently. Kandel, who won a share of the 2000 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, found that to build a memory that lasts hours, days or years, neurons must manufacture new proteins and expand the docks, as it were, to make the neurotransmitter traffic run more efficiently. Long-term memories must literally be built into the brain’s synapses. Kandel and other neuroscientists have generally assumed that once a memory is constructed, it is stable and can’t easily be undone. Or, as they put it, the memory is “consolidated.â€

According to this view, the brain’s memory system works something like a pen and notebook. For a brief time before the ink dries, it’s possible to smudge what’s written. But after the memory is consolidated, it changes very little. Sure, memories may fade over the years like an old letter (or even go up in flames if Alzheimer’s disease strikes), but under ordinary circumstances the content of the memory stays the same, no matter how many times it’s taken out and read. Nader would challenge this idea.

In what turned out to be a defining moment in his early career, Nader attended a lecture that Kandel gave at New York University about how memories are recorded. Nader got to wondering about what happens when a memory is recalled. Work with rodents dating back to the 1960s didn’t jibe with the consolidation theory. Researchers had found that a memory could be weakened if they gave an animal an electric shock or a drug that interferes with a particular neurotransmitter just after they prompted the animal to recall the memory. This suggested that memories were vulnerable to disruption even after they had been consolidated.

To think of it another way, the work suggested that filing an old memory away for long-term storage after it had been recalled was surprisingly similar to creating it the first time. Both building a new memory and tucking away an old one presumably involved building proteins at the synapse. The researchers had named that process “reconsolidation.†But others, including some prominent memory experts, had trouble replicating those findings in their own laboratories, so the idea wasn’t pursued.

To Nader and his colleagues, the experiment supports the idea that a memory is re-formed in the process of calling it up. “From our perspective, this looks a lot like memory reconsolidation,†says Oliver Hardt, a postdoctoral researcher in Nader’s lab.

Hardt and Nader say something similar might happen with flashbulb memories. People tend to have accurate memories for the basic facts of a momentous event—for example, that a total of four planes were hijacked in the September 11 attacks—but often misremember personal details such as where they were and what they were doing at the time. Hardt says this could be because these are two different types of memories that get reactivated in different situations. Television and other media coverage reinforce the central facts. But recalling the experience to other people may allow distortions to creep in. “When you retell it, the memory becomes plastic, and whatever is present around you in the environment can interfere with the original content of the memory,†Hardt says. In the days following September 11, for example, people likely repeatedly rehashed their own personal stories—“where were you when you heard the news?â€â€”in conversations with friends and family, perhaps allowing details of other people’s stories to mix with their own

Of course, there is the even bigger question: why are memories so unreliable?

Perhaps now we have a better understanding of how and why.

So how about talk therapy, and how about exposure in multimodal settings that call up these memories? How about this idea of Virtual Reality for PSTD?

In a way it scares me what technology like this can do now that we may be getting a sense of how memory, even long-term memory, may be more plastic than we want –Fahrenheit 451, A Clockwork Orange, or Bladerunner anybody?

I know, Nader is talking about traumatic situations, but what happens when we water-board confessions and use institutional pressures on kids and families?

Are we MAKING UP PEOPLES MINDS?

Then again, according to the liberally quoted Smithsonian article here, editing might be another way to learn from experience. If fond memories of an early love weren’t tempered by the knowledge of a disastrous breakup, or if recollections of difficult times weren’t offset by knowledge that things worked out in the end, we might not reap the benefits of these hard-earned life lessons. Perhaps it’s better if we can rewrite our memories every time we recall them. Nader suggests that reconsolidation may be the brain’s mechanism for recasting old memories in the light of everything that has happened since. In other words, it just might be what keeps us from living in the past– a survival mechanism.

But what if we can reshape memory and reduce trauma that has symptoms like:

- persistent frightening thoughts and memories of their ordeal

- feel emotionally numb, especially with people they were once close to.

- They may experience sleep problems, feel detached or numb, or be easily startled.

The idea seems appealing, but it scares me to think what may be coming out of Pandora’s X Box here.

I am all for relieving people of PTSD, but I am fascinated, and maybe a bit disturbed, by the potential other uses of this technology and science.

The research on memory just described begins to explain to some degree how a virtual environment can be used to MAKE UP SOMEONES MIND.

The following bit of text describes a treatment for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder using a virtual environment.

Developed by Virtually Better, with funding from the Naval Research Office, “Virtual Iraq†VR environment suitable for therapy of anxiety disorders resulting from the high-stress environment. The treatment involves exposing the patient to a virtual environment containing the feared situation rather than taking the patient into the actual environment or having the patient imagine the stimulus. The virtual environment is controlled by the therapist through a computer keyboard ensuring full control of the exposure to the programmed situations.

The system designed to treat military veterans suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Using components from the popular game Full Spectrum Warrior, psychologist Skip Rizzo and his colleagues introduce the patient to a virtual world simulating the sources of combat stress. The treatment objective is to help veterans come to terms with what they’ve experienced in places like Iraq and Afghanistan by immersing vets in the sights and sounds of those theaters of battle, including visual and sound effects of of gunshots. Virtual reality exposure treatment allows the therapist to manipulate situations to best suit the individual patient during a standard therapy hour (usually 45-50 minutes) and within the confines of the therapist’s office. By gradually re-introducing the patients to the experiences that triggered the trauma, the memory becomes tolerable. Early results from trials suggest virtual reality therapy is uniquely suited to a generation raised on video games.

According to Veterans Today:

During testimony on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other personality disorders affecting U.S. military veterans before the House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs way back on July 25, 2007, Dr. Sally Satel of the conservative think tank American Enterprise Institute (AEI) noted that VA disability determinations for PTSD needed to be tightened up to a take the emphasis off monetary compensation, in the same breath, she promoted ‘virtual reality war simulations’ mentioning Virtual Iraq, as state of the art treatment for PTSD. That was 2007 during the Bush administration, and in just three years during the Obama administration the Pentagon is now promoting it as state of the art treatment for PTSD!

Her intent was commendable, for she promotes catching PTSD in its early stages while still on active duty could prevent Veterans from a lifetime of dependency on VA compensation for PTSD. She also noted that, “A point worth raising here is the importance of qualified staffing at VA mental health facilities. Anecdotal reports suggest that many [VA] facilities do not have adequate numbers of clinicians who can perform cognitive-behavioral therapies. This is a deficit that must be addressed.â€

further,

Footnote 12 in her testimony to Congress on the treatment of PTSD was that “A specific form of exposure-desensitization therapy under development is called “Virtual Iraq.†Studies are in progress. The therapy was developed with funding from the Naval Research Office and is considered promising. The veteran [really active duty Soldier or Marine] wears a virtual-reality helmet and goggles and headphones. A therapist manipulates virtual situations via a keyboard to best  suit the individual patient during 45-50 minute sessions. By gradually re-introducing the patients to the experiences that triggered the trauma, the memory becomes tolerable and feelings of panic no longer accompany once-feared situations (such a driving on city streets, being in crowds). http://www.defense-update.com/products/v/VR-PTSD.htm, accessed July 21, 2007.

suit the individual patient during 45-50 minute sessions. By gradually re-introducing the patients to the experiences that triggered the trauma, the memory becomes tolerable and feelings of panic no longer accompany once-feared situations (such a driving on city streets, being in crowds). http://www.defense-update.com/products/v/VR-PTSD.htm, accessed July 21, 2007.

Veterans Today expressed concern about this method because of the implied cost savings that might be inherent in having soldiers participate in a virtual world rather than have a qualified, interested person to help. Having the new tool should not replace human interaction, but rather provide a medium that extends and facilitates. For those for whom talk therapy is not as effective because they have difficulty visualizing or using imagination, this virtual environment can be tremendously useful and alleviate suffering.

But the technology should not be a prescription without human community. It is evidently very effective.

Veterans Today Editorial Revision: Of note I have spoken to a young Air Force Mental Health Clinician who has told me that at least for him the treatment has had a positive impact. He was a ground troop in the Army in Iraq prior to getting his commission as a Psychologist in the Air Force. We have discussed his situation as being traumatized when he returned by feelings of panic as he drove the streets back home fearing IEDs. He once avoided being in a crowd for fear of suicide bombers. His experience with Virtual Iraq took away some of his feelings of anxiety and panic. Thus, we are not totally ignoring the positive effect virtual reality may be for a few of our troops coming forth to admit PTSD. This approach does have the positive aspect of trying to break down the stigma associated with going to the Mental Health clinics on Army and Marine base.

According to USC’s Dr. Albert “Skip†Rizzo, the founder of ‘Virtual Iraq’ presented his study on psychotherapy and stroke rehabilitation using video games and related technologies, such as virtual reality (VR). Dr. Rizzo presented three therapeutic areas he was working in at the time as part of the Games For Health day held at the University of Southern California [USC] on May 9th, Serious Games Sources.com promoting an entertainment video game convention called Games For Health 2006: Addressing PTSD, Psychotherapy & Stroke Rehabilitation with Games & Game Technologies.

Expose, Distract, and Motivate

The three main strategies Dr. Rizzo was using, he abbreviated as Expose, Distract and Motivate. To develop the therapeutic Virtual Reality (VR) systems he talked about, Dr. Rizzo worked with a host of other collaborators from different departments at USC, including among others Computer Science, Neuroscience, Annenberg School of Communication and Journalism, Department of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy, Department of Occupational Sciences, USC Keck School of Medicine, Department of Psychology, School of Gerontology & Neurology, Department of Cell and Neurobiology and also the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles.

According to Veteran’s Today;

The therapeutic approach Dr. Rizzo’s project took used gradual exposure to trauma in a manageable way, which eventually led to habituation and extinction of the PTSD syndrome. Does this mean that Dr. Rizzo has stumbled upon a cure for PTSD?

Normally, about 75% of soldiers will begin to display PTSD symptoms within about six months. With traditional [VIETNAM ERA] therapy, this is reduced to about 67%. But with exposure therapy, this can be reduced to only 27%.

“We normally rely on a patient’s imagination – what is called ‘imaginal therapy’, but we know we can provide the exposure to them through game environments,†said Rizzo. Problems with imaginal therapy include patients being unwilling or unable to visualize effectively or avoidance of the reminders of the trauma. When a patient can’t emotionally engage through imagination, it is unlikely that imaginal therapy will be effective.

Dr. Rizzo then mentioned several virtual tools, such as Virtual Vietnam from Emory University, as well as several others including a World Trade Center simulation from Cornell. Showing images from the Virtual Vietnam simulation, which depicts realistic scenes typical of that conflict; Dr. Rizzo cited a 1998 study that found, even 20 years after the events, that symptoms of sufferers of PTSD were reduced by 34 percent, while patients engaged in self-assessment though their symptoms saw reductions of 45 percent.

These are powerful outcomes, and also speak to concerns that I have as a parent, educator, and cognitive researcher — with the huge numbers of people playing games and having this gradual and in-depth exposure, who is there to model, guide, and share the experience with young people as they play games that are not meant for them. This does provide some leverage to those who say that games can lead to desensitization. There are groups, and have been, like the defunct Media and the Family, who believe that violent games need to be banned.

According to http://www.bullies2buddies.com/The-Virginia-Tech-Massacre, Anti-violent-video-game activists believe the Virginia Tech massacre is proof that we need to ban violent video games.

In the article they say,

But let’s not forget that most of the horrific events in world history were committed before there ever were video games. Millions of kids play violent video games every day, but random school shootings are extremely rare. If anything, Cho killed not because he played fantasy video games, but because he was inspired by the real-life Columbine shooting. Real life events are far more influential motivators of human behavior than imaginary ones. Cho obviously knew an awful lot about Columbine and felt justified committing a similar action. He probably planned the attack for the Columbine anniversary, April 20, but for whatever reasons, couldn’t wait another few days. Eric Harris and Dylan Klebald, the Columbine killers, killed because they knew about Hitler, whose birthday – April 20 – was the day they staged their massacre. Similarly, Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols, the Oklahoma City bombers, killed because they knew about the actions of Hitler. Their bombing took place one day shy of Hitler’s birthday. If we are to get rid of violent video games as a way of reducing violence, we should get rid of all violent news and history as well. Or perhaps we should delete the month of April from the calendar.

I agree with this take, but I am not so free and breezy.

With media and life experience, people need fellowship to talk about and make sense of their experience, and maybe even bounce ideas off of each other. That is part of the virtual reality intervention.

Where is the community and fellowship?

The folks involved in many violent actions against unsuspecting victims have often saturated their experience with inundations of bad behavior and justification for the violent act they are about to commit. The young men who directed the attack on the World Trade Center had evidently immersed themselves in the kind of lifestyles, pornography etc., that might have made their actions seem justified; as a moral act ridding the world of degenerative American liberties. The MYTH of America as Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah and Zeboim. These cities names have become synonymous with impenitent sin, and their fall with a proverbial manifestation of God’s wrath. Cf.Jude 1:7, Qur’an(S15)Al-Hijr:72-73. were destroyed by “brimstone and fire from the Lord out of heaven.”[Gen 19:24-25]. With the available choice for immorality, we allow for immorality, but hope that no one get’s hurt even if we don’t approve. That is the paradox of liberty–maybe?

The folks involved in many violent actions against unsuspecting victims have often saturated their experience with inundations of bad behavior and justification for the violent act they are about to commit. The young men who directed the attack on the World Trade Center had evidently immersed themselves in the kind of lifestyles, pornography etc., that might have made their actions seem justified; as a moral act ridding the world of degenerative American liberties. The MYTH of America as Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah and Zeboim. These cities names have become synonymous with impenitent sin, and their fall with a proverbial manifestation of God’s wrath. Cf.Jude 1:7, Qur’an(S15)Al-Hijr:72-73. were destroyed by “brimstone and fire from the Lord out of heaven.”[Gen 19:24-25]. With the available choice for immorality, we allow for immorality, but hope that no one get’s hurt even if we don’t approve. That is the paradox of liberty–maybe?

But also, these terrorists, let’s not call them misunderstood, were also told that their acts would forgive them for their debauchery and actions–but again, was there any community to question these, their acts of debauchery leading up to their demise? Did their act lead to ascension and the fulfillment of receiving 72 virgins–although, nothing in the Koran specifically states that the faithful are allotted 72 virgins apiece. For this elaboration we turn to the hadith, traditional sayings traced with varying degrees of credibility to Muhammad. Hadith number 2,562 in the collection known as the Sunan al-Tirmidhi says, “The least [reward] for the people of Heaven is 80,000 servants and 72 wives, over which stands a dome of pearls, aquamarine and ruby.”

Now more than ever, community is important.

In a recent post by blogger, the Shifted Librarian, Jaron Lanier’s book You Are Not a GadÂget was reviewed and a few key issues about how technology is locking us down. One of Lanier’s conÂcerns is how deciÂsions made in the design of our digÂiÂtal tools lock us in to behavÂiors that reduce — and even remove — our humanÂity.

The context of the blog post I am drawing from was not meant to support the argument that floats as a sub-text in this post–that we may be getting closer to understanding the way we make moral decisions and judgment from prior experience, memory, and my own concern:

that somehow science and technology are going to somehow fill the gap for parenting, friendship, guidance in human relations, health care, business management decisions, and education.

Isn’t this kind of the same promise Hadith number 2,562 makes to the terrorist?

When we remove ourselves from humanity, it makes it easier to generate stereotype, assign blame, and be less troubled with really understanding that there might be a real problem we could address and solve.

It seems the further away the decision maker is from the point of implementation, the less likely they are to understand the real implications of the reduction of one-to-one, or one-to-many, face-to-face, interactions that are not locked down by the constraints of the medium through which those people are attempting to experience.

I am an advocate for games, and I am also an advocate for spending more time with your children and friends who play them –that is spending time away from the game system to talk about the values they hold, the experiences they had in the game, and the realities and importance of life in community where people gather in public spaces.

To do that, the adults in our community must be willing to spend that time with children and neighbors and talk about the experience.

TIME folks, shared time.

In one example, I was speaking in front of group of over 300 people (at a university) on how games would make the University Obsolete (provocative on purpose).

A hand went up and a professor I personally knew told me with disgust,

“I will not expose my son to this shit!” referring to video games.

I asked her, do you tell your son he is not allowed to play video games?

She said yes.

I asked if his friends played games.

She said yes.

I asked if he ever went to their houses.

She said yes.

I asked her, do you want to give up your opportunity to share experience with your son with media he is interested in, and share values?

She sat down.

By making this completely forbidden, she had taken herself out of the conversation about values and the content in the games.

We cannot do that as community members, because as the research is showing, reconsolidating experience as memory changes memory.

Who do you want “making up your kids minds?”

I think this is also what we call parenting and raising young–talking and sharing values through shared experience.

This does not show up on a test score by the way.

I understand the need to protect young people from inappropriate media and content — I did not let M-rated games in my classroom–but I was familiar with many of them and could talk about them with the students.

I want to know what they are doing and who they are–and good teachers, friends, and parents do this.

In the first games project we engaged with in 2004, I had placed 3 young women in a randomized cooperative group in my classroom with a young man who had brought Mortal Combat.

This game, one of the reasons the ESRB was established:

The girls were really turned off, even though this was a Teen game for 13+, and I had High School Seniors at the time (seventeen-eighteen).

But what was interesting was the report they gave on how women were portrayed in the game when I encouraged them to do a Feminist analysis:

- Few women

- Not dressed for battle, but for the libido of young men

- smaller weapons

- could not hit as hard for damage

- could hit more and had greater dexterity

Great you say? So what. . .

But this led into a constructed controversy activity where we questioned whether representation of women in this form influences the way we see women in society, and the way young women see themselves and come to build perceptions of self-worth.

Half the class believed that media representation of women did actually influence how young women see themselves, and the other half said that it was just a game.

I asked them to prepare 10 talking-points to support their positions for debate, when they were done, I asked them to project and list 10 talking-points for what they thought the opposing side would list as their positions.

Then I flung them a twist, I made them argue for the opposite side.

Kids said that this was one of the best activities that they had been part of during all their years at Roosevelt– I took that as a great compliment because there were some really great teachers there.

We can structure engagement, and young people really do want to talk about these things and they really are interested in education — relevant education and issues.

(you can read this to get principles for designing a classroom to do what I did, and this to understand how I used games for language arts curriculum)

Public Engagement in Digital Spaces

I am not sure that we can have a real public engagement in a digital space. We can try through communities like WoW etc., but what makes that whole argument silly has been my own experience watching groups who have played WoW for extended periods of time make an effort to actually meet other players in their guilds and interact person to person. I make sure to introduce myself to Facebook friends at conferences even though we may have an online history, I find it more satisfying to shake hands and share a moment.

Last year at the Games in Education Conference, a number of WoW players got together who had hours and hours of time shared in digital space, but they still made a trip to New York from Oregon, Pennsylvania, etc.

It was fun to share with them and participate in the interaction knowing this back-story at dinner.

Only Connect —

E. M. Forrester said:

” Only connect! … Only connect the prose and the passion, and both will be exalted, and human love will be seen at its height. Live in fragments no longer. Only connect, and the beast and the monk, robbed of the isolation that is life to either, will die.”

I think we do connect online, but not in the same way–at least not until computers can distribute pheromones and people post their real pictures at online dating portals!

No, I do not think the digital games offer the degrees of freedom that actual contact and real play (maybe throwing a Frisbee) does.

Plato discusses public spaces in the Republic as the foundation for democracy and meritocracies–but maybe this is not enough.

I say this because Jim Gee makes a case for this with Affinity Groups and games as the ultimate meritocracy are based upon skills and activity, and this is why people gather, and this is easily achieved in these online environments.

But skills aren’t what it is all about. In the words of Napolean Dynamite,

“You know, like nunchuku skills, bow hunting skills, computer hacking skills… Girls only want boyfriends who have great skills.”

People acquire skills to build connections to other people.

I know that Jim (if you are reading this Jim, feel free to straighten me out here) does not believe that WoW is a replacement for actual interpersonal interaction, and that we cannot always be in competition for merit and entitlement.

That approach is contrary to his position especially as it relates to the overemphasis in schools with the ridiculous focus on assessment.

Even Diane Ravitch, who advocated for the emphasis on testing has changed directions based on evidence showing that,

Ravitch advocates for a national curriculum — maybe this is a good idea AS LONG AS WE ARE TALKING ABOUT METHODS, and not content — Hello Texas School Board.

To extricate this whole issue of community and MAKING UP OUR MINDS

Hannah Arendtsays that we must move beyond “the state of appearance” we often share in public.

There are three features of the public sphere and of the sphere of politics in general that are central to Arendt’s conception of citizenship. These are, first, its artificial or constructed quality; second, its spatial quality; and, third, the distinction between public and private interests.

The following is excerpted from Plato online:

As regards the first feature, Arendt always stressed the artificiality of public life and of political activities in general, the fact that they are man-made and constructed rather than natural or given. She regarded this artificiality as something to be celebrated rather than deplored. Politics for her was not the result of some natural predisposition, or the realization of the inherent traits of human nature. Rather, it was a cultural achievement of the first order, enabling individuals to transcend the necessities of life and to fashion a world within which free political action and discourse could flourish.

The stress on the artificiality of politics has a number of important consequences. For example, Arendt emphasized that the principle of political equality does not rest on a theory of natural rights or on some natural condition that precedes the constitution of the political realm. Rather, it is an attribute of citizenship which individuals acquire upon entering the public realm and which can secured only by democratic political institutions.

Another consequence of Arendt’s stress on the artificiality of political life is evident in her rejection of all neo-romantic appeals to the volk and to ethnic identity as the basis for political community. She maintained that one’s ethnic, religious, or racial identity was irrelevant to one’s identity as a citizen, and that it should never be made the basis of membership in a political community.

Arendt’s emphasis on the formal qualities of citizenship made her position rather distant from those advocates of participation in the 1960’s who saw it in terms of recapturing a sense of intimacy, of warmth and authenticity. For Arendt political participation was important because it permitted the establishment of relations of civility and solidarity among citizens. She claimed that the ties of intimacy and warmth can never become political since they represent psychological substitutes for the loss of the common world. The only truly political ties are those of civic friendship and solidarity, since they make political demands and preserve reference to the world. For Arendt, therefore, the danger of trying to recapture the sense of intimacy and warmth, of authenticity and communal feelings is that one loses the public values of impartiality, civic friendship, and solidarity.

The second feature stressed by Arendt has to do with the spatial quality of public life, with the fact that political activities are located in a public space where citizens are able to meet one another, exchange their opinions and debate their differences, and search for some collective solution to their problems. Politics, for Arendt, is a matter of people sharing a common world and a common space of appearance so that public concerns can emerge and be articulated from different perspectives. In her view, it is not enough to have a collection of private individuals voting separately and anonymously according to their private opinions. Rather, these individuals must be able to see and talk to one another in public, to meet in a public-political space, so that their differences as well as their commonalities can emerge and become the subject of democratic debate.

This notion of a common public space helps us to understand how political opinions can be formed which are neither reducible to private, idiosyncratic preferences, on the one hand, nor to a unanimous collective opinion, on the other. Arendt herself distrusted the term “public opinion,†since it suggested the mindless unanimity of mass society. In her view representative opinions could arise only when citizens actually confronted one another in a public space, so that they could examine an issue from a number of different perspectives, modify their views, and enlarge their standpoint to incorporate that of others. Political opinions, she claimed, can never be formed in private; rather, they are formed, tested, and enlarged only within a public context of argumentation and debate.

Another implication of Arendt’s stress on the spatial quality of politics has to do with the question of how a collection of distinct individuals can be united to form a political community. For Arendt the unity that may be achieved in a political community is neither the result of religious or ethnic affinity, not the expression of some common value system. Rather, the unity in question can be attained by sharing a public space and a set of political institutions, and engaging in the practices and activities which are characteristic of that space and those institutions.

A further implication of Arendt’s conception of the spatial quality of politics is that since politics is a public activity, one cannot be part of it without in some sense being present in a public space. To be engaged in politics means actively participating in the various public forums where the decisions affecting one’s community are taken. Arendt’s insistence on the importance of direct participation in politics is thus based on the idea that, since politics is something that needs a worldly location and can only happen in a public space, then if one is not present in such a space one is simply not engaged in politics.

This public or world-centered conception of politics lies also at the basis of the third feature stressed by Arendt, the distinction between public and private interests. According to Arendt, political activity is not a means to an end, but an end in itself; one does not engage in political action to promote one’s welfare, but to realize the principles intrinsic to political life, such as freedom, equality, justice, and solidarity. In a late essay entitled “Public Rights and Private Interests†(PRPI) Arendt discusses the difference between one’s life as an individual and one’s life as a citizen, between the life spent on one’s own and the life spent in common with others. She argues that our public interest as citizens is quite distinct from our private interest as individuals. The public interest is not the sum of private interests, nor their highest common denominator, nor even the total of enlightened self-interests. In fact, it has little to do with our private interests, since it concerns the world that lies beyond the self, that was there before our birth and that will be there after our death, a world that finds embodiment in activities and institutions with their own intrinsic purposes which might often be at odds with our short-term and private interests. The public interest refers, therefore, to the interests of a public world which we share as citizens and which we can pursue and enjoy only by going beyond our private self-interest

I taught with games in public schools beginning in 2004, and found that young people gather together to talk about them and it is a form of social capital.

Kids who don’t have experience with games are often outcast, or hopefully have some other activity that they can socialize around.

Games and media are important to kids, just like guys talk sports, or outboard motors, and women talk shopping–sorry to stereotype–kids talk about the activities they value and build identities and social groups around them.

My fear is that adults, educators, and members of the community will, or have withdrawn from learning and experiencing these games and popular culture dismissing it as lowbrow and simpleton.

But I dare you Dostoevskians to play Bio Shock. These games are not easy, and oddly enough they are in many cases transmedial extensions of classical narratives.

I had a student tell me that Sonic the Hedgehog was like Odysseus, ” He was just trying to get home.”

I loved that one!

Through the act of diminishing the role that these games have in people’s lives, we lose the ability to share and transfer our values.

What right do we have in judging the new media and activities, when we ourselves, have withdrawn with disdain and contempt?

The new groups surrounding these media do not know you are gone first off, and we are missing out in stretching our own values.

Back to memory

What if evidence of what we thought we saw, believed to be true, and often fight for, might be a memory that we hoped really happened?

We have always really known this, Lenin once said

A lie told often enough becomes the truth.

What do we keep telling ourselves in isolation?

Perhaps it should be obvious, but the kids who played games with their parents, in my studies, were better at the games, had a greater range of strategy and ability in decision making, had advanced help-seeking behaviors, and had clearly been parented.

They were also what I would call, more grounded. Unflappable, less likely to be set off, and less needy seeming.

These kids also did better in adjusting to conflict, making and keeping friends, and scoring in academics in general.

Those who had game systems, but did not show the characteristics mentioned above tended towards very simple games that were more about aiming, shooting, driving, and timing.

Most did not describe much parental involvement in their lives.

They also had difficulty with reading and decision making, and had been removed from class for disruption, in some cases.

A game system, like a television, radio, or any cultural artifact needs to be talked about and shared–how about a family activity?

Given all of this, the simple message should be ~ we need to talk about this.

What do we need to talk about?

- Memory is unreliable and we can make it up as we go

- Because of this we can help people who have been in great trauma . . . We can also worry about how this might otherwise be used.

- When we talk about memory and moral decision making, it is important that we have community.

- Community takes time, dedicated space, and a willingness to move beyond the superficial.

- Popular culture can be easily dismissed, as well as the young people who participate in it, but we are missing out on a chance to broaden and deepen and share our values when we withdraw and demonize.

The American Heart Association has teamed up with Nintendo of America to promote physically active play as part of a healthy lifestyle. They believe that active-play video games are a great option for the entire family to incorporate more exercise into their day and spend quality time together. I have to agree that active play is great for getting the blood pumping, but let’s get serious about which games are going to get the heart really pumping!

The American Heart Association has teamed up with Nintendo of America to promote physically active play as part of a healthy lifestyle. They believe that active-play video games are a great option for the entire family to incorporate more exercise into their day and spend quality time together. I have to agree that active play is great for getting the blood pumping, but let’s get serious about which games are going to get the heart really pumping!

At least it will get people together, maybe get them to stand up like many of the advertisements show — I am sorry to be so cynical here, but hey, I was part of a research program that gave away 30 X Boxes with DDR pads and software, Â only to find that the kids were happy to play Halo and other games that had nothing to do with the high impact activities like jumping to increase bone density and reduce their teen obesity, in fact exacerbating the problem.

Yes, there are an abundance of obese tweens, ages 8-14 years, and during this time, it is a special period of growth where bone density growth is exponential. Read Dance Dance Education to learn more about this– or just consider 8-10 minutes of jumping a day.

What happened in the bone density study was that many of the kids really wanted to have the reputation of being gamers, but did not follow through.

Most kids say they are gamers, but they are not.

Read the article Reading Comprehension as a Submedial Trait, and you may find like I did, that most kids are not very good at games. They can learn on the fly, like we all can with casual games like the Wii and easy stuff like party games, but most could not figure out a complex game–only one student in 12 was able to get in the airlock in the game Metroid Prime in an after school games club, even though these kids said they were avid gamers (Dubbels, 2008).

That whole idea of kids are natural gamers and digital natives is hooey. Without a support network, interest, and reinforcement, which is pointed out in the Dance Dance Education article, most kids just use the social capital of knowledge to make friendships and cool groups, and hardly ever have to prove anything but a desire and enjoyment of playing– few ever really get their immigration papers to digital nation.

But I digress, the Wii is just the sort of system that allows for the kind of casual video game play that does not place high cognitive demand on decision making or knowledge seeking behaviors. It might get people out of their chairs and at least interacting with a thing like virtual tennis or bowling (which is quite fun) and maybe even Snow Boarding — which is a blast.

This would be a great step forward as compared to flipping and settling on a rerun of Law and Order. I know, I know, cynical again, but after teaching with games in the classroom for 7 years, you might be too. Games just do not do much teaching beyond the simple mechanics that move the player forward in the game unless the individual is playing a great variety of games and is participating in the secondary knowledge market of games like guides, play groups, fan fiction, and franchised narratives and accessories with lots of modeling from more experienced problem solvers. We have always known this about learning, that is why kids learn from what they see us do, not from what we tell them to do.

And please don’t think games don’t have potential. They have lot’s of potential–much more than books in many  respects, but books will not and should not be replaced by games in the classroom, and teachers will not be either (obvious subtext). I know everyone wants to get on the games bandwagon and proclaim them the great potential classroom tools they are, just like they did the radio in the 20’s, the film in the 50’s, etc. (Cuban, 1994).

Challenging complex games create challenge and opportunity for complex thinking.

But without the correct pedagogy, games are just entertainment that may inspire learning, but may not create any meaningful transfer to skills and decision making that improve the quality of life.

I have used many simple games to do this, but the game will not do it alone — parents need to model behavior, just like I had to create inquiry frameworks to create cognitive growth when we studied games at school. It is the same with this endorsement of the Wii by the American Heart Association. Do not expect to get a work out playing Mario Galaxy, as great a game as it is.

The American Heart Association recommends that all adults get at least 150 minutes of moderate physical activity per week. Children and adolescents should do 60 minutes or more per day of aerobic physical activity. Nearly 70 percent of Americans are not reaching these goals. Buying a video game will not change poor lifestyle choices like deep fried pork rinds washed down with a coke for a pre-dinner snack and an evening of couch coma kung fu with a Wii a nun chuk.

I’m just sayin’

www.ampainsoc.org

For immediate release Contact:Â Chuck Weber

(847) 705-1802, cpweber@weberpr.com

News from American Pain Society’s 29th Annual Scientific Conference

Video Games and Virtual Reality Experiences Prove Helpful as Pain Relievers in Children and Adults

BALTIMORE, MD, May 6, 2010 – When children and adults with acute and chronic pain become immersed in video game action, they receive some analgesic benefit, and pain researchers presenting at the American Pain Society’s (www.ampainsoc.org) annual scientific meeting here today reported that virtual reality is proving to be effective in reducing anxiety and acute pain caused by painful medical procedures and could be useful for treating chronic pain.

“Virtual reality produces a modulating effect that is endogenous, so the analgesic influence is not simply a result of distraction but may also impact how the brain responds to painful stimuli,†said Jeffrey I. Gold, Ph.D., associate professor of anesthesiology and pediatrics, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California and director of the Pediatric Pain Management Clinic at Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles. “The focus is drawn to the game not the pain or the medical procedure, while the virtual reality experience engages visual and other senses.â€

While moderating a symposium entitled “Virtual Reality and Pain Management,†Dr. Gold noted that the exact mechanistic/neurobiological basis responsible for the VR analgesic effect of video games is unknown, but a likely explanation is the immersive, attention-grabbing, multi-sensory and gaming nature of VR. These aspects of VR may produce an endogenous modulatory effect, which involves a network of higher cortical (e.g., anterior cingulate cortex) and subcortical (e.g., the amygdale, hypothalamus) regions known to be associated with attention, distraction and emotion. Studies measuring the benefit of virtual reality pain management, therefore, have employed experimental pain stimuli, such as thermal pain and cold pressure tests, to turn pain responses on and off as subjects participate in virtual reality experiences.

“In my current NIH-funded study, I am using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure the effects of VR on experimental pain,†Dr. Gold explained. “The objective is to measure the cortical regions of interest involved in VR, while exposing the participant to video racing games with and without experimental pain stimuli.â€

Lynnda M. Dahlquist, Ph.D., a clinical child psychologist and professor of psychology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, reviewed her most recent laboratory research studies

examining the use of virtual reality and other computer/videogame technologies to provide distraction-based acute pain management.

The use of video games and virtual reality distraction (VRD) technology for procedural pain management in both pre-schoolers and elementary to middle school children, reported Dr. Dahlquist, yielded promising results in increasing pain tolerance “with potentially significant future clinical applications for more effective pain reduction techniques for youth with chronic and acute pain. However, more research is needed to know for certain if there is real world VRD application in such pain-generating procedures as cleansing wounds, cancer treatment, immunization, injections and burn care.â€

Children interacting with a virtual environment by watching video games demonstrated a small pain tolerance improvement during exposure to ice cold water stimulation, according to Dr. Dahlquist, but she recorded significantly greater pain tolerance for kids wearing specially-equipped video helmets when they actually interacted with the virtual environment.

“Our aim is to know what about VRD makes it effective in pain tolerance lab studies with children and what are the best ways to use it for optimum results,†explained Dr. Dahlquist, noting that any distraction is better than none at all in pain minimization. “Is it just the amazing graphics in the video games or is it because youngsters are truly more distracted through their direct interaction with the virtual environment?â€

VRD’s impact on pain tolerance levels varied by children’s ages, indicating that age may influence how effective video game interaction will be. “We must better understand at what ages VRD provides the greatest benefit in moderating acute pain and at what age, if any, that it can be too much or be limiting.â€

In one study using video helmets for virtual environment interactivity, the special equipment had little positive impact with children ages six to ten, but for those over ten years of age, “there was a much longer tolerance of the pain of the cold water exposure, leading us to further study to determine what aspect or aspects of cognitive development and neurological function account for this difference among youth.

“Having dealt clinically for more than 15 years with children with acute and chronic illness,†Dr. Dahlquist summed up, “my genuine hope is that virtual reality activity can alleviate the anxiety of approaching pain and the pain experience itself.â€

About the American Pain Society

About the American Pain Society

Based in Glenview, Ill., the American Pain Society (APS) is a multidisciplinary community that brings together a diverse group of scientists, clinicians and other professionals to increase the knowledge of pain and transform public policy and clinical practice to reduce pain-related suffering. APS was founded in 1978 with 510 charter members. From the outset, the group was conceived as a multidisciplinary organization. APS has enjoyed solid growth since its early days and today has approximately 3,200 members. The Board of Directors includes physicians, nurses, psychologists, basic scientists, pharmacists, policy analysts and more.

# # #

Technology and Literacy

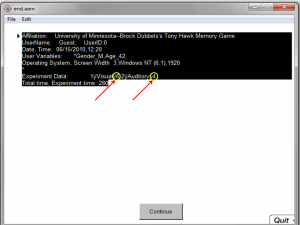

Current and Emerging Practices with Student 2.0 and Beyond

David G. O’Brien Brock Dubbels

Guiding Questions

- What technology tools and Web 2.0 applications are important for literacy learning

- What are the best practices involving technology and literacies

- How can instruction in the classroom and curriculum be enhanced by using new and evolving technologies that support digital literacy practices?

This chapter provides an overview of evolving research and theoretical frameworks on technologies and literacy, particularly digital technologies, with implications for adolescents’ literacy engagement. We suggest future directions for engaging students with technology and provide resources that support sound practices.

Evolving Research on Digital Technologies:

From Frameworks to Best Practice

When Kamil, Intrator, and Kim (2000) tackled a synthesis of research on technologies and literacy, they termed the task a conundrum. Given the rapidly evolving landscape of various technologies, that review, now dated (as this chapter soon will be), is still insightful both in reviewing a diversity of topics and the evolving importance of each. For example, at the turn of the decade, these researchers gave us historical footing in matters such as how computers and software may be used to improve reading and writing (Kamil, 1982), and to motivate learners (Hague & Mason, 1986). They noted the rising significance of hypertext and hypermedia, and foreshadowed the explosion of interest in the intersection of traditional literacies and digital media, which, at the turn of the decade, comprised a new program of inquiry (Reinking, McKenna, Labbo, & Kieffer, 1998). Finally, they also highlighted the social and collaborative importance of students working on stand-alone computers or in collaborative network environments, cited the paucity of research overall

on technologies and literacy, and expressed optimism about the future of computers as instructional tools.

In the same volume that featured the synthesis by as Kamil, Intrator, and Kim, Leu (2000) used the phrase “literacy as technological deixis†(p. 745) to refer to the constantly changing nature of literacy due to rapidly morphing technologies. Leu’s characterization is crucial, because he posits that these literacies are moving targets, evolving too rapidly to be adequately studied. If best practices rest on a solid research foundation, then, in the case of technologies and literacy we haven’t even begun to know what best practices are. Nevertheless, even in the midst of a shallow bed of “empirical†studies—that is, studies of specific effects, over time, with statistical power, or studies of carefully described and documented, contextualized practices—compelling frameworks have emerged, with implications for how technologies enable new literacy practices. Best practices, if based on solid frameworks rather than a carefully focused research program, can be extrapolated from the frameworks and be the basis for sound instruction and curriculum planning. In this chapter we bridge some of these frameworks with instructional practice.

The relatively brief evolution of technologies and literacy has led us from computers and software as self-contained instructional platforms to a networked virtual world that computers enable. In the past 10 years or so, we have moved from viewing the Web as primarily a source of information and as a sort of dynamic hypertext with increasingly sophisticated search engines, to Web 2.0. Albeit a fuzzy term that has accrued definitions ranging from simply a new attitude about the old Web to a host of perspectives about a completely new Web, Web 2.0 presents exciting possibilities for enhancing instruction and learning. This new Web is an open environment with virtual applications; it is more dependent on people than on hardware; it more participatory than a one-sided flow of information (e.g., blogging, wikis, social networks); it is more responsive to our needs (e.g., mapping a route to a previously unknown destination). Perhaps most important, Web 2.0 is more open to sharing of ideas, media, and even computer code (Miller, 2005). The presence of Web 2.0 is about the World Wide Web (WWW) as a platform for production. Software that users would normally purchase and install from a disk or download is now hosted on the Internet. In a sense, Web 2.0 affords anyone access to the largest stage yet conceived. Educationally, it has the potential to diminish the broadcast mode of information transmission that has reduced individual interests and engagement. Instead, learners can now have at their disposal studio-quality tools that enhance production, appreciation, recognition, and performance, and above all, provide access to a worldwide audience.

Whereas research on computers and reading and writing has remained sparse, research on the myriad literacy practices involved in the Web 2.0 phenomenon is sparse but growing rapidly and is informed by many theoretical frames and fields, most of which overlap—for example, multiliteracies (Cope & Kalantzis, 2000; New London Group, 1996), new literacies and new literacy studies (Coiro, Knobel, Lankshear, & Leu, 2008; Kist, 2005; Knobel & Lankshear, 2007), media studies and new media studies (Hobbs, 2007; Kress, 2003), and critical media literacy and popular culture (Alvermann, Moon, & Hagood, 1999; Beach & O’Brien, 2008), to name a few.

Each of these frameworks has its own dynamics for describing and studying literacy practices, and each is inextricably intertwined with other frameworks. In the rapidly emerging research base, most of the designs are highly contextualized and theoretically tantalizing, but few studies are gauged to identify specific generalizable practices. For example, the studies designed around some of the aforementioned frameworks vary in terms of methodology (spanning the full range of human and cognitive sciences); they vary in terms of which data are collected, which settings (physical and virtual) are studied, and how learners are defined (e.g., as information processors, real selves, virtual selves, identity constructors). Hence, we can present here only a small sampling and complement the descriptions with some “best practice†exemplars, reminding readers of the caveat that “research-based†practices represent glimpses or snapshots taken along the rapidly moving field.

Reader and Writer 2.0: New Literates and New Literacies

What is important about technologies and literacies, especially when considering adolescents? What should we cull from the myriad evolving frameworks and perspectives to be able to present something useful for teachers and learners at this point in time given this rapidly changing texture. First, we want to present the adolescent learner, the person we call Student 2.0, starting with a vignette.

High school students in Eden Prairie, Minnesota, a suburb of Minneapolis,posted photos on Facebook revealing themselves partying with alcohol, in violation of school rules. Following an investigation by school officials, disciplinary action was taken against 13 students. Students who believed that that the administration went too far walked out of school in protest; some of the parents threatened legal action (Xiong & Relerford, 2008). Scholars of digitally mediated popular culture challenged theadults, parents and school officials alike, to evaluate more critically what had happened: High school students felt a compelling need to express themselves as digital authors and document a relatively common practice, partying with alcohol. And issuing sanctions assumes that the practice had not been widespread before it was expressed publicly on Facebook. Prosecution of the rule offenders would only serve to remind the documentors to be more careful. The new media scholars also reminded the youth as authors to consider more carefully their audience in the future. When you post on Facebook, you create for everyone, including school administrators and parents. Some students who were interviewed on television reacted to the disciplinary measures by saying that their rights to free speech were violated, that the school administrators had no jurisdiction, because the activities happened off of school grounds. Others went back to Facebook to start a new group page to defend their actions.The Eden Prairie incident, albeit intriguing as a local interest piece about controversial legal and ethical issues regarding the Web 2.0, illustrates the trend of online content creation among youth. Rather than just use the Web to locate information, students are involved in content creation, that continues to grow, with 64% of online “teenagers†ages 12 to 17 engaging in at least one type of content creation, up from 57% of online teens in 2004 (Lenhart, Madden, Macgill, & Smith, 2007). In this national survey by the Pew Internet and American Life Project, 55% of online teens ages 12–17 say that they have

created a profile on a social networking site, such as Facebook or MySpace, and 47% of online teens claim to have uploaded photos where others can see them. Even though those students posting online photos sometimes restrict access, they expect feedback. Nearly 9 out of 10 teens who post photos online (89%) say that people comment on their postings at least some of the time. The number of teen bloggers nearly doubled from 2004 to 2006, with girls leading boys in blogging, and the younger, upcoming girls more likely to outblog The important issue for teachers is that these student authors are composing in a visual mode and reading comments printed in response; their peer readers (who are also most likely composers) are increasingly “reading†images and composing text responses or print messages in blogs and expecting critical responses. In short, students increasingly seem to engage in the

types of reading and writing they either don’t engage in, or don’t prefer, at school.

Experienced teachers can remember when stand-alone computers were going to revolutionize education; they can recall when the Internet was a cumbersome, text-based environment rather than an engaging graphical environment called the WWW. Those of us who, as literacy educators, have spent our careers studying how young people interact with printed texts are now faced with a new landscape that renders many of our theoretical models, instructional frameworks, and “best†practices based on these print models inadequate or even obsolete. Print text remains important but, as noted, expression is increasingly multimodal (Kress & Van Leeuwen, 2001). Reading and writing youth are increasingly likely to express ideas using different semiotic modes, including print, visual, and audio modes, and to create hybrid texts that defy typical associations between modes and what they traditionally represent.

When David worked with struggling readers in a high school Literacy Lab, the students, many of whom did not choose to read and write using print, wrote complex multimodal texts on a range of topics. They were very articulate about the affordances of various modes, and how those affordances influenced their choices in composition. For example, one group of students working a project exploring the impact of violence in the medion in adolescents, decided when to use images instead of print to communicate their ideas more effectively and passionately. They carefully planned how to juxtapose images and print to convey meaning. What would traditionally have been termed a “report†was instead a mul- timedia project, which they presented to parents and others at the school Open House evening. Brock has created a game studies unit, in which students study the qualities of their video games and create a technical document called a Walk- through using blogs, a wiki, video, and an animated slide show embedded into the blog. Students could read, compare, and evaluate other students’ work. Brock used an RSS feed (really simple syndication, a feed link to syndicated content) and had the blogs collected with bloglines, a way to both aggregate the student work and provide social networking through the WWW-based platforms and the comment sections for students.From these two examples, you can see that the reading and composition enabled by these digital technologies is spatial rather than linear. Linearity has been replaced by reading and writing in virtual textual space—where a hot link lures the reader away from one page and on to the next, and from print to images and video, deeper and deeper into one’s unique textual experience, and writers can post, broadcast, and receive responses. Scholars are already starting to look at the new spatial and temporal dimensions of digital literacies, as well as the compatibilities and incompatibilities of these dimensions

with traditional spatial and temporal dimensions of schools (Leander, 2007). Researchers are also studying new literacy environments such as web pages using research paradigms derived from reading print on paper—for example, Coiro and Dobler’s (2007) work extending traditional comprehension theories to study online reading comprehension. Coiro and Dobler argue that although we know a lot about the reading strategies that skilled readers use to understand print in linear formats, we know little about the proficiencies needed to comprehend text in “electronic†environments. McEneaney (2006) cogently argues that the traditional theoretical frameworks, including so-called “interactive theories†(from cognitive or transactional perspectives) are too strongly based in a traditional notion of print to be useful. With what are the new literates interacting? McEneaney contends that the text can “act on†the environment: The text can create the reader, just as the reader through the dynamics of online environments, can create or change the text.

But the new literates also encounter new challenges. The new textual spatiality lacks the kinesthetic texture of books; readers lose their “places†and even the ability to feel the touch of the page as they do when they flip paper pages back, then reorient themselves on the page (Evans & Po, 2007). The feel of the text is replaced by the feel of a finger on a mouse or a key. The imaging that helps a reader maintain and access the previous page might be replaced by multiple mental images of more rapidly changing texts, or mental images replaced by actual images. What Evans and Po call the fluidity of the digital or electronic texts invites readers to alter the text more readily, more easily. We come full circle with a tension faced by readers of the digital texts. On the one hand, this text fluidity begs readers to alter texts, to pick alternative texts, and to mix and match texts; on the other hand, this new textuality, with texts unfolding at every mouse click, places the text itself more in the control of the reader. The text the reader creates, often unwittingly via a series of clicks or cuts and pastes, may address the reader/writer in unexpected ways. One of the most exciting prospects for educators is the unlimited range of texts, from traditional print modes to various hybrids, including print texts, visual texts, audio texts, and even various types of performance texts that students can now create, as they themselves are “created†or changed by those texts. The new literates can navigate through a collage of print, images, videos, and sounds, choosing and juxtaposing modalities, and bending old spatial and temporal constraints to communicate to peers and to others throughout the world.

Beach and O’Brien (2008), in drawing from both the philosophy of mind and neuroscience (e.g., Clark, 2003; Restak, 2003) propose that the students of the “digital generation†have more digitally adept brains; they read and write differently than youth from even 10 years ago, because their existence

in the mediasphere, the barrage of multimodal information they encounter daily, the constant availability of multiple tech tools at their fingertips, and the convergence enabling immediate use and production of media have changed the way they process multimedially. Prensky (2001) has posited a similar scenario. The Beach and O’Brien proposal (2008), in response to a Kaiser Family Foundation study (Foehr, 2006) of young people ages 8–18 and widely disseminated in the popular press, shows that even though the total amount of time devoted to media use remains about the same as 5 years ago (6.5

hours a day), the amount of time devoted to multitasking, using multiple forms of media concurrently (e.g., surfing the Web while listening to an MPEG-1 Audio Layer 3 (MP3) and checking text messages), is on the rise. Beach and O’Brien (2008) contend that multitasking is not accurate, because it implies the ability to engage in several activities at the same time or, more accurately,to switch attention rapidly among activities to gain efficiency in completing work. They instead characterized this often seamless juggling as multimediating (Lankshear & Knobel, 2003), because it more accurately involves not only multimodal attention shifts but also seems to include a new facility and flexibility in processing and producing multimodal texts. The missing piece in characterizing the new literates is that we continue to appraise them using outdated models of reading, text processing, and learning. Instead, we need

to think of them as more adept at using technologies to read, compose, and “socialize.â€

Texts 2.0: From the Page to the Screen

Let us revisit the question posed in the last section—What is important about technologies and literacies?—and this time consider the evolving kinds of texts that youth are reading and writing. Again, we have to choose among compelling frameworks and perspectives. One salient issue surrounding the

evolving technologies is how the notion of “text†is changing. We are “moving from the page to the screen†(Kress, 2003). Kress notes that the screen privileges images. He also makes a case for the ambiguity of images and the necessity of print text for helping the viewer understand context and make a

directed interpretation of images. As educators, we have to concede that texts are increasingly multimodal (Jewitt & Kress, 2003). In multimodal reading and composing, ideas and concepts are represented with print texts, visual texts (photographs, video, animations), audio texts (music, audio narration, sound effects), and even dramatic or other artistic performances (drama, dance, spoken-word) (O’Brien & Scharber, 2008).

A second change is the increasing popularity of hybrid texts that are unlike most of the longer, connected discourse with which many of us grew up. For example, textoids are on the rise. These texts were originally defined as specially created research texts that lacked the coherence and structure of naturally occurring texts from typical genres (Graesser, Millis, & Zwaan, 1997) or contrived instructional texts (Pearson, 2004). Ironically, these once- contrived texts are ubiquitous in online environments. The term textoids now refers to fleeting texts that are transported from one place to another and are constantly changing (e.g., Wikipedia entries, pasted into a student’s report and edited to fit into the new textual context); they are also textual bursts of information sent to cell phones as text messages. Short textoids or text bursts are displacing longer discourse as readers expect more choices in accessing information and entertainment faster in quick clicks. At the same time, the sheer number and range of genres of these textoids, the juxtaposition of textoids with other media, and the retention of the more traditional, longer discourse, makes reading in online text environments more challenging than reading in traditional print environments.

The typical ways of describing and distinguishing texts from one another, such as using text structure, no longer apply (McEneaney, 2006). Electronic texts defy such classification, because they may be short and contrived to produce a targeted burst to get attention (the textoids); they are not linear but

spatial (hypertexts, hypermedia). Single textoids or pages or articles are linear, but they exist in virtual space, with a multitude of other possible texts. In short, the texts have virtual structure that is much more dynamic than static structures assigned to single print texts.

Present Technology Tools and Web 2.0 Applications

As we noted, Web 2.0 tools are about production, and they are hosted on the Web to enable a range of activities. As the access to bandwidth increases, and computers are equipped with greater image/video processing capacity, these tools will become invaluable in engaging youth. Young people will use these tools not only to develop literacy and numeracy skills but also to continue to hone their technological skills in the production, communication networking, data mining, and problem solving that are increasingly valued in the global economy. In the past, many of the tools now available as Web-based tools were expensive, limited to single machines, and difficult to use. These same tools, such as word processing, multimedia production, and network communications tools are now free, shareable, collaborative, and perceived as both meaningful and enjoyable by young people. Moreover, the tools are

part of young people’s daily lives. In addition, the personal electronics that many young people carry in their pockets, backpacks, and purses are more powerful than the computers that inhabited labs not even 5 years ago. With the advent of new applications and relatively cheap storage on the Web, these portable devices neither perform the bulk of processing nor store the outputs of processing; they are access devices—Web portals, with small screens and keyboards or other ways to input data. For example if you want to work with pictures, you can access a portal such as Flickr to view and manage pictures; if you want to create a document of just about any stripe, you can go to Google Docs and make slide shows; engage in word processing; construct spreadsheets; and store, share, and collaborate with writing partners.

Teachers can use many of these tools to extend and to enhance the learning experience of their students. The tools present challenges in developing best practices because they are neither repositories of content nor self- contained curricula. Rather, they can be used by creative teachers who are

able to draw from existing content domains, themes, and conceptual frameworks as they work within the applications; the tools can provide supportive environments for producing content, sharing and collaborating around content, and hosting public displays of users’ productions. Hence, the tools are not useful without the context of a larger unit or lesson plan, and instructional and learning frameworks that support activities and literate practices enabled by the tools. Teachers must understand clearly their instructional and learning objectives and goals, and students must know how the tools can help them meet those goals. Otherwise, the tools, which students sometimesknow well and can use for entertainment, revert to users’ tools for pleasure and interests, easily circumventing instructional or learning practices desired by teachers. Next, we review some Web 2.0 tools that enable these practices, and describe the features of each, presenting examples of how we have used them with students.

MySpace

We start with the nemesis of most computer classrooms and labs. For example, Brock was observing another teacher’s students during a drafting class. The students were working in a lab with high-end three-dimensional drafting software. During downtime between instructions that were broadcast over the

public address system, students often checked their MySpace pages. Although the site was blocked in the district, many students easily overcame the obstacle by searching for a proxy server that granted them access. A proxy server is a website that has a name accepted by the firewall, so it is allowed—it is kind of like using a fake ID. Although students may not know how it works, they have learned how to do it. And no matter how savvy the information technology (IT) department, the almost infinite supply of new proxy servers and webpages, with directions targeting youth who want to jump the school restrictions, makes sites deemed objectionable by school districts difficult to block.

On the one hand, to the digital immigrants and the inhabitants of the Institution of Old Learning (O’Brien & Bauer, 2005), MySpace represents an uncontrolled virtual space that distracts students from work and enables socializing and forms of expression incompatible with the organization and temporal control of school. On the other hand, for digital natives, “assimilated†digital immigrants, and new literacies advocates, MySpace is a dynamic forum of multimodal expression. It is also a place where young people socialize with peers around the world, put pictures up, write in slang, stream music and video, and engage in instant messaging. They are able to blog, to embed flash animations—in short, to engage in almost limitless expression using a range of multimodal literacies. It is really an example of students expressing themselves in the same way they dress, decorate their rooms, or draw in their notebooks.