CFP: Gaming, gender, and the female perspective

The purpose of this special issue is to investigate and explore female roles, participation, and representation in video games and the video games industry.

Authors are invited to submit manuscripts that

- Examine the emergence and after effects of gamer gate

- Traditions of games that support professional female players

- Female fan perspectives

- Representation of women in games

- Market analysis

- Meta-analyses of existing research on women in games

- Female experiences of scholarship and industry

- Answer specific questions such as:

- How should feminist theory inform game user research?

- What are the methodologies for conducting feminist games research, and the uses and design of games for gender issues?

- Case studies, worked examples, empirical and phenomenological, application of psychological and humanist approaches?

- Field research

- Face to face interviewing

- Creation of user tests

- Gathering and organizing statistics

- Define Audience

- User scenarios

- Creating Personas

- Product design

- Feature writing

- Requirement writing

- Content surveys

- Graphic Arts

- Interaction design

- Information architecture

- Process flows

- Usability

- Prototype development

- Interface layout and design

- Wire frames

- Visual design

- Taxonomy and terminology creation

- Copywriting

- Working with programmers and SMEs

- Brainstorm and managing scope (requirement) creep

- Design and UX culture

Potential authors are encouraged to contact Brock R. Dubbels (Dubbels@mcmaster.ca) to ask about the appropriateness of their topic.

Deadline for Submission June 15, 2017.

Authors should submit their manuscripts to the submission system using the following link:

http://www.igi-global.com/authorseditors/titlesubmission/newproject.aspx

(Please note authors will need to create a member profile in order to upload a manuscript.)

Manuscripts should be submitted in APA format.

They will typically be 5000-8000 words in length.

Full submission guidelines can be found at: http://www.igi-global.com/journals/guidelines-for-submission.aspx

Mission – IJGCMS is a peer-reviewed, international journal devoted to the theoretical and empirical understanding of electronic games and computer-mediated simulations. IJGCMS publishes research articles, theoretical critiques, and book reviews related to the development and evaluation of games and computer-mediated simulations. One main goal of this peer-reviewed, international journal is to promote a deep conceptual and empirical understanding of the roles of electronic games and computer-mediated simulations across multiple disciplines. A second goal is to help build a significant bridge between research and practice on electronic gaming and simulations, supporting the work of researchers, practitioners, and policymakers.

Post – Test

Puzzles pt 2

Link a (Use Class number 8220)

Abstract Announcement for International Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations (IJGCMS) 7(1)

The contents of the latest issue of:

International Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations (IJGCMS)

Volume 7, Issue 1, January – March 2015

Published: Quarterly in Print and Electronically

ISSN: 1942-3888; EISSN: 1942-3896;

Published by IGI Global Publishing, Hershey, USA

www.igi-global.com/ijgcms

Editor(s)-in-Chief: Brock Dubbels (McMaster University, Canada)

Note: There are no submission or acceptance fees for manuscripts submitted to the International Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations (IJGCMS). All manuscripts are accepted based on a double-blind peer review editorial process.

Brock R. Dubbels PhD., McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

To obtain a copy of the Editorial Preface, click on the link below.

www.igi-global.com/pdf.aspx?tid=125440&ptid=118613&ctid=15&t=And This One Was Just Right: In Search of Goldilocks in Player Experience

ARTICLE 1

Flow Genres: The Varieties of Video Game Experience

Ondrej Hrabec (Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic), Vladimír Chrz (Institute of Psychology, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Prague, Czech Republic)

The goal of this theoretical study is to conceptually revise the flow theory formulated originally by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Concept of flow is one of the most frequently used terms that describe an optimal experience while performing activity and this does not apply only for video game industry. In this article we discuss the varieties of flow experience with respect to video games. Further, the authors emphasize relativity of the original concept of flow, understood as a universal experience of independent nature in terms of activity or personality of the participant. Following detailed analysis of existing literature and our previous empirical study, they define the concept of flow as a genre triad that portrays experience of climax, ilinx, and ludic trance. A further revision and extension of the original concept of flow is deemed necessary in order to map the variety of user experiences while playing video games with sufficient precision.

To obtain a copy of the entire article, click on the link below.

www.igi-global.com/article/flow-genres/125443

To read a PDF sample of this article, click on the link below.

www.igi-global.com/viewtitlesample.aspx?id=125443

ARTICLE 2

Investigating Real-time Predictors of Engagement: Implications for Adaptive Videogames and Online Training

David Sharek (North Carolina State Univeristy, Raleigh, NC, USA), Eric Wiebe (North Carolina State Univeristy, Raleigh, NC, USA)

Engagement is a worthwhile psychological construct to examine in the context of video games and online training. In this context, previous research suggests that the more engaged a person is, the more likely they are to experience overall positive affect while performing at a high level. This research builds on theories of engagement, Flow Theory, and Cognitive Load Theory, to operationalize engagement in terms of cognitive load, affect, and performance. An adaptive algorithm was then developed to test the proposed operationalization of engagement. Using a puzzle-based video game, player performance and engagement was compared across three conditions: adaptive gameplay, a traditional linear gameplay, and choice-based gameplay. Results show that those in the adaptive gameplay condition performed higher compared to those in the other two conditions without any degradation of overall affect or self-report of engagement.

To obtain a copy of the entire article, click on the link below.

www.igi-global.com/article/investigating-real-time-predictors-of-engagement/125444

To read a PDF sample of this article, click on the link below.

www.igi-global.com/viewtitlesample.aspx?id=125444

ARTICLE 3

Design and Development of a Simulation for Testing the Effects of Instructional Gaming Characteristics on Learning of Basic Statistical Skills

Elena Novak (School of Teacher Education, Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green, KY, USA), Tristan E. Johnson (Graduate School of Engineering, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA)

Considerable resources have been invested in examining the game design principles that best foster learning. One way to understand what constitutes a well-designed instructional game is to examine the relationship between gaming characteristics and actual learning. This report discusses the lessons learned from the design and development process of instructional simulations that are enhanced by competition and storyline gaming characteristics and developed as instructional interventions for a study on the effects of gaming characteristics on learning effectiveness and engagement. The goal of the instructional simulations was to engage college students in learning the statistics concepts of standard deviation and the empirical rule. A pilot study followed by a small-scale experimental study were conducted to improve the value and effectiveness of these designed simulations. Based on these findings, specific practical implications are offered for designing actual learning environments that are enhanced by competition and storyline gaming elements.

To obtain a copy of the entire article, click on the link below.

www.igi-global.com/article/design-and-development-of-a-simulation-for-testing-the-effects-of-instructional-gaming-characteristics-on-learning-of-basic-statistical-skills/125445

To read a PDF sample of this article, click on the link below.

www.igi-global.com/viewtitlesample.aspx?id=125445

ARTICLE 4

Personality Impressions of World of Warcraft Players Based on Their Avatars and Usernames: Consensus but No Accuracy

Gabriella M. Harari (The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA), Lindsay T. Graham (The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA), Samuel D. Gosling (The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA & School of Psychological Sciences, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia)

Every week an estimated 20 million people collectively spend hundreds of millions of hours playing massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs). Here the authors investigate whether avatars in one such game, the World of Warcraft (WoW), convey accurate information about their players’ personalities. They assessed consensus and accuracy of avatar-based impressions for 299 WoW players. The authors examined impressions based on avatars alone, and images of avatars presented along with usernames. The personality impressions yielded moderate consensus (avatar-only mean ICC = .32; avatar plus username mean ICC = .66), but no accuracy (avatar only mean r = .03; avatar plus username mean r = .01). A lens-model analysis suggests that observers made use of avatar features when forming impressions, but the features had little validity. Discussion focuses on what factors might explain the pattern of consensus but no accuracy, and on why the results might differ from those based on other virtual domains and virtual worlds.

To obtain a copy of the entire article, click on the link below.

www.igi-global.com/article/personality-impressions-of-world-of-warcraft-players-based-on-their-avatars-and-usernames/125446

To read a PDF sample of this article, click on the link below.

www.igi-global.com/viewtitlesample.aspx?id=125446

BOOK REVIEW

Reality is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World

Anna Baralt (University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA), Albert D. Ritzhaupt (University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA)

To obtain a copy of the Book Review, click on the link below.

www.igi-global.com/pdf.aspx?tid=125447&ptid=118613&ctid=17&t=Reality is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World

For full copies of the above articles, check for this issue of the International Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations (IJGCMS) in your institution’s library. This journal is also included in the IGI Global aggregated “InfoSci-Journals” database: www.igi-global.com/isj.

CALL FOR PAPERS

Mission of IJGCMS:

The International Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations (IJGCMS) publishes research articles, theoretical critiques, and book reviews related to the development and evaluation of games and computer-mediated simulations. One main goal of this peer-reviewed, international journal is to promote a deep conceptual and empirical understanding of the roles of electronic games and computer-mediated simulations across multiple disciplines. A second goal is to help build a significant bridge between research and practice on electronic gaming and simulations, supporting the work of researchers, practitioners, and policymakers.

Indices of IJGCMS:

- ACM Digital Library

- Bacon’s Media Directory

- Cabell’s Directories

- Compendex (Elsevier Engineering Index)

- DBLP

- GetCited

- Google Scholar

- INSPEC

- JournalTOCs

- MediaFinder

- PsycINFO®

- SCOPUS

- The Standard Periodical Directory

- Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory

Coverage of IJGCMS:

Recommended topics include (but are not limited to) the following:

- Cognitive, social, and emotional impact of games and simulations

- Critical reviews and meta-analyses of existing game and simulation literature

- Current and future trends, technologies, and strategies related to game, simulation development, and implementation

- Electronic games and simulations in government, business, and the workforce

- Electronic games and simulations in teaching and learning

- Frameworks to understand the societal and cultural impacts of games and simulations

- Impact of game and simulation development use on race and gender game and simulation design

- Innovative and current research methods and methodologies to study electronic games and simulations

- Psychological aspects of gaming

- Teaching of games and simulations at multiple age and grade levels

Interested authors should consult the journal’s manuscript submission guidelines www.igi-global.com/calls-for-papers/international-journal-gaming-computer-mediated/1125

Interested authors should consult the journal’s manuscript submission guidelines www.igi-global.com/calls-for-papers/international-journal-gaming-computer-mediated/1125

Join us at the Terryberry Library for an afternoon of fun and game development.

In the following few sessions we will be learning about Blockly for coding, and then building our own version of Pong, and making our own little AI.

First Step: Create a new account at http://code.org when you have done so, add the code BYQYAP to be in my section.

Programming Puzzles — 20 minutes

Second Step: Create new account at http://scratch.mit.edu/

Work on our version of Pong

For this activity, we will be playing a game to learn about programming.

We would like to know, what is a process.

Can you tell us?

The recent tragedies of gun violence have resulted in a renewed interest into the role of violent video games and aggressive, anti-social, and violent behavior. The current view is that many young people who commit violent crimes do so because they play violent video games.

In some ways, this is like saying that the use of suntan lotion increases the likelihood of drowning. In research, this is called a spurious correlation. A spurious correlation consists of two events or variables that have no direct causal connection–such as suntan lotion and drowning.

A spurious correlation is often supported by coincidence, or happens over and over, but is actually caused by an unidentified, third factor. There may be a relationship in a correlation:

- A (violent video game play) causes B (aggression and violence),

- B (aggression and violence) causes A (violent video game play),

- OR

- C (a third factor such as antisocial traits and depression) cause both A and B.

There are three explanations for games and violence:

- The causal view: video game violence exposure has a learning-based causal influence on subsequent serious aggression–A causes B;

- A priori view: individuals with high levels of a priori aggression are subsequently drawn to video game violence–B causes A:

- No relation view: that any correlation between the video game playing and aggression is due to underlying third variables such as depression and anti-social traits–C causes both A and B.

Ferguson (2010) controlled for these three views.

The Causal View: Social-Learning – A (video games) causes B (aggression):

For children with low antisocial traits, media violence exposure was associated with less criminal behavior.

The A Priori View – B (antisocial traits) causes A (choice of violent games and acts):

Antisocial children who are most inclined toward criminal behavior may also be those most likely to select violent media. Additionally, it may be that only the most antisocial children will be affected by media violence exposure leading to aggressive behavior and violent crimes. This is the explanation favored by Ferguson et al. (2008) based on similar findings as well as by Kutner and Olson (2007). This should not be underestimated. More research is needed to understand this, but as Giumetti and Markey (2007) alternatively suggest that, although violent video games are harmless for the vast majority of children, for those with preexisting high antisocial traits, video game violence may exacerbate these traits. More research on this is definitely needed.

The No-Relation View: third variables that predicted serious aggression and violence – C (depression anti-social traits) causes both A (violent aggressive behavior) and B (choosing violent games).

The evidence provided by Ferguson (2010) indicates that playing violent games does not lead to violent aggressive behavior.Instead, there was more evidence for the “No Relation” Hypothesis. That Games did not lead to the aggressive/violent behavior.

Instead, it was evidence suggested that antisocial traits and depression predict violent and aggressive behavior.

When outcomes from the Child Behavior Check List were calculated for effect size, (the strength of the phenomenon), depression and symptoms of pathological aggression were seen as strong effects(.5, .62) as well as for bullying (.32).

- So why do studies of violent video game play show increased aggression?

- Why do we see behaviors such as frustration, anger, anxiety after our children play games?

There may be a other factors at play: competitiveness.

Isolationism and exclusion

- Although games can provide a sort of coping mechanism, but they can also present a distraction for not dealing directly with an issue.

- Conversely, having an enjoyable activity may support the individual in a time of challenge and provide an effective coping mechanism that supports them in conjunction with dealing directly with an issue.

If a child, adult, or young adult already has symptoms of depression, anti-social traits, and are further isolated, this is a recipe for danger. For the individual and perhaps the community. In the words of E.M. Forester, we need to “Only connect!”

Just as evolutionary theories suggest that laughter is a survival mechanism for newborns to assure attachment and bonding so that they are cared for, there are also evolutionary reasons for play (Sutton-Smith, 1997).

Play is typically defined as having intrinsic goals that serve no other objective; play is freely chosen, spontaneous and voluntary; and in utilitarian terms it is inherently unproductive (Garvey, 1990). This intrinsic motivation is ideally what we would like to see more of in work. Often we view work as extrinsically motivated, where the activity is externally regulated based upon receiving a reward or avoiding punishment (Deci & Ryan, 2004).

Whereas work emphasizes certainty in outcomes, and is often not intrinsically motivated. “Biologically, its function is to reinforce the organism’s variability in the face of rigidifications of successful adaptation” (Sutton-Smith, 1997, 231).

Lev Vygotsky (1977) claimed that children begin to develop the ability to dissociate, or create imaginative microworlds in play. Objects used in play may assume some of the cognitive load, and transition the child from play as imagination in action, to the ability visualize and create mental representation from memory as imagination as play without action.

This is powerful, especially when used purposefully for instruction. The reframing of context though play can strengthen societies by uniting individuals through ritual activity and helping them achieve common goals (Huizinga, 1950). Toys, jokes, and games allow groups to face collective fears about cultural issues that might otherwise overwhelm the individual: bigotry, racism, rejection, terrorism, addiction, and poverty.

Games can structure play so that equity is created through rules, tools, roles, methods, and language, which gives everyone the opportunity to share spontaneous authentic experience and build connections (Corsaro, 1985) without having to experience the stress or tension of the outside world. In many ways it can be a time out. It can be respite from the world . . . A stepping into a magic circle (Huizinga, 1949).

But not all games facilitate play.

And not all activities are games. . . even when they are intended to be.

Play is in the eye of the player.

There are activities that we create for fun and competition, but these are not necessarily games.

Callois (1961) has a number of categories that help us to look at rules and experience, but without the reduction of consequence in the activity (punitive outcomes), many folks would be hesitant to place them in the genre we call games.

This seems to be the major drawback of the gamification movement — a leader board, or a competition, does not a game make.

Maybe games can be made up on the spot.

Some might call a discussion such as this academic gamesmanship.

I think it is important to point out that play is what creates games (Dubbels, 2010).

Not games creating play.

Games may attract people who want to be playful (Dubbels, 2009), but the context and way in which they are approached is what differentiates play from work.

Play is a mode of, or approach to, an activity.

Play places a social moratorium on consequence. When we do or say something that can get us in trouble, we will often claim that “I was just playing”.

Play works along a spectrum, from imaginative and discovery play to work.

It is all dependent upon the subjunctive mood, or ethos (see Ambiguity of Play by Sutton-Smith, and Play Groups, Corsaro, in Dubbels, 2009)

Games are a structured form of play (Dubbels, 2008).

But games do not necessarily facilitate play.

If we play monopoly with real money, are we still playing when it becomes high stakes?

I would not call that play. I don’t think that Geertz, Sutton-Smith, and others would call that play either.

What is important is our approach to an activity. At some point, play becomes work

We tend to develop identities around play, and want the reputation as being playful (Dubbels, 2009).

When we look at games, we are seeing a movement away from play towards work (Dubbels, 2011).

Play is a special form of learning, and often play evolves into activities with rule structures–these can be viewed as special cases of play, games, or something more serious (see Deep Play, Geertz in Dubbels, 2009).

I think it is really important to have play in mind when thinking about games, if you want gameplay.

Works cited:

Dubbels, B.R. (2008) Video games, reading, and transmedial comprehension. In R. E. Ferdig (Ed.),Reference. Information ScienceHandbook of research on effective electronic gaming in education.

Dubbels, B. R. (2009) Dance Dance Education and Rites of Passage—Lessons learned about the importance of play in sustaining engagement from a high school “girl gamer” based upon socio- and cultural-cognitive analysis for designing instructional environments to elicit and sustain engagement through identity construction. International Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations. 1(4) IGI Publishers.

Dubbels, B.R. (2010) Designing Learning Activities for Sustained Engagement — Four Social Learning Theories Coded and Folded into Principals for Instructional Design through Phenomenological Interview and Discourse Analysis. In Discoveries in Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations: New Interdisciplinary Applications.

Dubbels, B.R. (2012) The Importance of Construct Validity in Designing Serious Games for Return on Investment. Ludica Medica Special Issue. International Journal of Games and Computer Mediated Simulations.

I am concerned that Gamefication obfuscates the real issue in learning:

Transfer.

Is there evidence that game-based learning leads to far transfer?

Without learning transfer, it doesn’t matter how a person learned–whether from a piece of software, watching an expert, rote memorization, or the back of cereal box. What is important is that learning occurred, and how we know that learning occurred.

This leads to issues of assessment and evaluation.

Transfer and Games:Â How do we assess this?

The typical response from gameficators is that assessment does not measure the complex learning from games. I have been there and said that. Â But I have learned that is overly dismissive of assessment and utterly simplistic. As I investigated assessment and psychometrics, I have learned how simplistic were my statements. Games themselves are assessment tools, and I learned that by learning about assessment.

This Gameficator–(yes I am now going to 3rd person)–had to seek knowledge beyond his ludic and narratological powers. He had to learn the mysteries and great lore of psychometrics, instructional design, and educational psychology. It was through this journey into the dark arts, that he has been able to overcome some of the traps of Captain Obvious, and his insidious powers to sidetrack and obfuscate through jargonification,and worse–like taking credit for previously documented phenomena by imposing a new name. . . kind of like my renaming Canada to the now improved, muchmorebetter name: Candyland.

In reality, I had to learn the language and content domain of learning to be an effective instructional designer, just as children learn the language and content domains of science, literature, math, and civics.

What I have learned through my journey, is that if a learner cannot explain a concept, that this inability to explain and demonstrate may be an indicator that the learning from the game experience is not crystallized–that the learner does not have a conceptual understanding that can be explained or expressed by that learner.

Do games deliver this?

Does gamefied learning deliver this?

Gameficators need to address this if this is to be more than a captivating trend.

I am fearful that the good that comes from this trend will not matter if we are only creating  jargonification (even if it is more accessible). It is not enough to redescribe an established instructional design technique if we cannot demonstrate its effectiveness.  We should be asking how learning in game-like contexts enhances learning and how to measure that.

Measurement and testing are important because well-designed tests and measures can deliver an assessment of crystallized knowledge–does the learner have a chunked conceptual understanding of a concept, such as “resistance”, “average”, “setting”?

Measurement and testing are important because well-designed tests and measures can deliver an assessment of crystallized knowledge–does the learner have a chunked conceptual understanding of a concept, such as “resistance”, “average”, “setting”?

Sure, students may have a gist understanding of a concept. The teacher may even see this qualitatively, but the student cannot express it in a test. So is that comprehension? I think not. The point of the test is an un-scaffolded demonstration of comprehension.

Maybe the game player has demonstrated the concept of “resistance” in a game by choosing a boat with less resistance to go faster in the game space– but this is not evidence that they understand the term conceptually. This example from a game may be an important aspect of perceptual learning, that may lead to the eventual ability to explain (conceptual learning); but it is not evidence of comprehension of “resistance” as a concept.

So when we look at game based learning, we should be asking what it does best, not whether it is better. Games can become a type of assessment where contextual knowledge is demonstrated. But we need to go beyond perceptual knowledge–reacting correctly in context and across contexts–to conceptual knowledge: the ability to explain and demonstrate a concept.

My feeling is that one should be skeptical of Gameficators that pontificate without pointing to the traditions in educational research. If Gamefication advocates want to influence education and assessment, they should attempt to learn the history, and provide evidential differences from the established terms they seek  to replace.

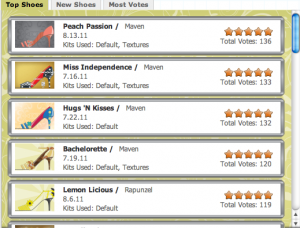

A darker shadow is cast

Another concern I have is that  perhaps not all gameficators are created equal. Maybe some gameficators are not really advocatingfor the game elements that are really fundamental aspects of games? Maybe there are people with no ludic-narratological powers donning the cape of gamefication! I must ask, is this leaderboard what makes for “gameness”? Or does a completion task-bar make for gamey experience?

Maybe there are people with no ludic-narratological powers donning the cape of gamefication! I must ask, is this leaderboard what makes for “gameness”? Or does a completion task-bar make for gamey experience?

Does this leaderboard for shoe preference tell us anything but shoe preference? Where is the game?

Are there some hidden game mechanics that I am failing to apprehend?

Is this just villainy?

Here are a couple of ideas that echo my own concerns:

It seems to me, that:

- some of the elements of gamefication rely heavily on aspects of games that are not new, just rebranded.

- some of the elements of gamefication aren’t really “gamey”.

What I like about games is that games can provide multimodal experiences, and provide context and prior knowledge without the interference of years of practice-this is new. Games accelerate learning by reducing the some of the gatekeeping issues. Now a person without the strength, dexterity and madness can share in some of the experience of riding skateboard off a ramp.  The benefit of games may be in the increased richness of a virtual interactive experience,  and provide the immediate task competencies without the time required to become competent. Games provide a protocol, expedite, and scalffold players toward a fidelity of conceptual experience.

For example, in RIDE, the player is immediately able to do tricks that require many years of practice because the game exaggerates the fidelity of experience. Â This cuts the time it might take to develop conceptual knowledge but reducing the the necessity of coordination, balance, dexterity and insanity to ride a skateboard up a ramp and do a trick in the air and then land unscathed.

Gameficators might embrace this notion.

Games can enhance learning in a classroom, and enhance what is already called experiential learning.

My point:

words, terms, concepts, and domain praxis matter.

Additionally, we seem to be missing the BIG IDEA:

- that the way we structure problems is likely predictive of a successful solutionHerb Simon expressed the idea in his book The Sciences of the Artificial this way:

“solving a problem simply means representing it so as to make the solution transparent.” (1981: p. 153)

Games can help structure problems.

But do they help learners understand how to structure a problem. Do they deliver conceptualized knowledge? Common vocabulary indicative of a content domain?

The issue is really about What Games are Good at Doing, not whether they are better than some other traditional form of instruction.

Do they help us learn how to learn? Do they lead to crystallized conceptual knowledge that is found in the use of common vocabulary? In physics class, when we mention “resistance”, students should offer more than

“Resistance is futile”

or, a correct but non-applicable answer such as “an unwillingness to comply”.

The key is that the student can express the expected knowledge of the content domain in relation to the word. This is often what we test for. So how do games lead to this outcome?

I am not hear to give gameficators a hard time–I have a gamefication badge (self-created)–but I would like to know that when my learning is gamefied that the gameficator had some knowledge from the last century of instructional design and learning research, just as I want my physics student to know that resistance as an operationalized concept in science, not a popular cultural saying from the BORG.

The concerns expressed here are applicable in most learning contexts. But if we are going to advocate the use games, then perhaps we should look at how good games are effective, as well as how good lessons are structured. Perhaps more importantly,

- we may need to examine our prevalent misunderstandings about learning assessment;

- perhaps explore the big ideas and lessons that come from years educational psychology research, rather than just renaming and creating new platform without realizing or acknowledging, that current ideas in gamefication stand on the established shoulders of giants from a century of educational research.

Jargonification is a big concern. So lets make our words matter and also look back as we look forward. Games are potentially powerful tools for learning, but not all may be effective in every purpose or context. What does the research say?

I am hopeful gamefication delivers a closer look at how game-like instructional design may enhance successful learning.