CFP Special Issue On: SURGE, Physics Games, and the Role of Design

Submission Due Date

5/15/2017

Guest Editors

Douglas Clark, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA

Introduction

The purpose of this special issue is to investigate the role of design in the efficacy of physics games in terms of what is learned, by whom, and how. Importantly, studies should move beyond basic media comparisons (e.g., game versus non-game) to instead focus on the role of design and specifics about players’ learning processes. Thus, invoking the terminology proposed by Richard Mayer (2011), the focus should be on value-added and cognitive consequences approaches rather than media comparison approaches. Note that a broad range of research methodologies including a full gamut of qualitative, ethnographic, and microgenetic methodologies are encouraged as well as quantitative and data-mining perspectives. Furthermore, the focal outcomes and design qualities analyzed can span the range of functional, emotional, transformational, and social value elements outlined by Almquist, Senior, and Bloch (2016).

Recommended Topics

Authors are invited to submit manuscripts that

- Focus on the role of design beyond simple medium (i.e., move beyond simple of tests of whether physics games can support learning to instead focus on how the design of the game, learning environment, and social setting influence what is learned, by whom, and how).

- Explore learning in games from the SURGE constellation of physics games and other physics games using qualitative, mixed, design-based research, quantitative, data-mining, or other methodologies.

- Focus on formal, recreational, and/or informal learning settings.

- Focus on any combination of player, student, teacher, designer, and/or any of other participants.

- Answer specific questions such as:

- How do specific approaches to integrating learning constructs from educational psychology (e.g., work examples, signaling, self-explanation) impact the efficacy of these approaches within digital physics games for learning?

- How do elements of design impact the value experienced by players in terms of the elements of functional, emotional, transformational, and social value outlined by Almquist, Senior, and Bloch (2016)?

- What is the role of the teacher in interaction with students and the design of a game in terms of learning outcomes?

- How does game design interact with gender in terms of what is learned, by whom, and how?

- How can designers balance learning goals and game-play goals to best support a diverse range of players and learners?

- How do specific sets of design features interact with players’ learning processes and game-play goals?

Submission Procedure

Potential authors are encouraged to contact Douglas Clark (clark@vanderbilt.edu) to ask about the appropriateness of their topic.

Authors should submit their manuscripts to the submission system using the link at the bottom of the call (Please note authors will need to create a member profile in order to upload a manuscript.).

Manuscripts should be submitted in APA format.

They will typically be 5000-12000 words in length.

Full submission guidelines can be found at: http://www.igi-global.com/publish/contributor-resources/before-you-write/

All submissions and inquiries should be directed to the attention of:

Douglas Clark

Guest Editor

International Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations (IJGCMS)

Email: clark@vanderbilt.edu

I am concerned that Gamefication obfuscates the real issue in learning:

Transfer.

Is there evidence that game-based learning leads to far transfer?

Without learning transfer, it doesn’t matter how a person learned–whether from a piece of software, watching an expert, rote memorization, or the back of cereal box. What is important is that learning occurred, and how we know that learning occurred.

This leads to issues of assessment and evaluation.

Transfer and Games:Â How do we assess this?

The typical response from gameficators is that assessment does not measure the complex learning from games. I have been there and said that. Â But I have learned that is overly dismissive of assessment and utterly simplistic. As I investigated assessment and psychometrics, I have learned how simplistic were my statements. Games themselves are assessment tools, and I learned that by learning about assessment.

This Gameficator–(yes I am now going to 3rd person)–had to seek knowledge beyond his ludic and narratological powers. He had to learn the mysteries and great lore of psychometrics, instructional design, and educational psychology. It was through this journey into the dark arts, that he has been able to overcome some of the traps of Captain Obvious, and his insidious powers to sidetrack and obfuscate through jargonification,and worse–like taking credit for previously documented phenomena by imposing a new name. . . kind of like my renaming Canada to the now improved, muchmorebetter name: Candyland.

In reality, I had to learn the language and content domain of learning to be an effective instructional designer, just as children learn the language and content domains of science, literature, math, and civics.

What I have learned through my journey, is that if a learner cannot explain a concept, that this inability to explain and demonstrate may be an indicator that the learning from the game experience is not crystallized–that the learner does not have a conceptual understanding that can be explained or expressed by that learner.

Do games deliver this?

Does gamefied learning deliver this?

Gameficators need to address this if this is to be more than a captivating trend.

I am fearful that the good that comes from this trend will not matter if we are only creating  jargonification (even if it is more accessible). It is not enough to redescribe an established instructional design technique if we cannot demonstrate its effectiveness.  We should be asking how learning in game-like contexts enhances learning and how to measure that.

Measurement and testing are important because well-designed tests and measures can deliver an assessment of crystallized knowledge–does the learner have a chunked conceptual understanding of a concept, such as “resistance”, “average”, “setting”?

Measurement and testing are important because well-designed tests and measures can deliver an assessment of crystallized knowledge–does the learner have a chunked conceptual understanding of a concept, such as “resistance”, “average”, “setting”?

Sure, students may have a gist understanding of a concept. The teacher may even see this qualitatively, but the student cannot express it in a test. So is that comprehension? I think not. The point of the test is an un-scaffolded demonstration of comprehension.

Maybe the game player has demonstrated the concept of “resistance” in a game by choosing a boat with less resistance to go faster in the game space– but this is not evidence that they understand the term conceptually. This example from a game may be an important aspect of perceptual learning, that may lead to the eventual ability to explain (conceptual learning); but it is not evidence of comprehension of “resistance” as a concept.

So when we look at game based learning, we should be asking what it does best, not whether it is better. Games can become a type of assessment where contextual knowledge is demonstrated. But we need to go beyond perceptual knowledge–reacting correctly in context and across contexts–to conceptual knowledge: the ability to explain and demonstrate a concept.

My feeling is that one should be skeptical of Gameficators that pontificate without pointing to the traditions in educational research. If Gamefication advocates want to influence education and assessment, they should attempt to learn the history, and provide evidential differences from the established terms they seek  to replace.

A darker shadow is cast

Another concern I have is that  perhaps not all gameficators are created equal. Maybe some gameficators are not really advocatingfor the game elements that are really fundamental aspects of games? Maybe there are people with no ludic-narratological powers donning the cape of gamefication! I must ask, is this leaderboard what makes for “gameness”? Or does a completion task-bar make for gamey experience?

Maybe there are people with no ludic-narratological powers donning the cape of gamefication! I must ask, is this leaderboard what makes for “gameness”? Or does a completion task-bar make for gamey experience?

Does this leaderboard for shoe preference tell us anything but shoe preference? Where is the game?

Are there some hidden game mechanics that I am failing to apprehend?

Is this just villainy?

Here are a couple of ideas that echo my own concerns:

It seems to me, that:

- some of the elements of gamefication rely heavily on aspects of games that are not new, just rebranded.

- some of the elements of gamefication aren’t really “gamey”.

What I like about games is that games can provide multimodal experiences, and provide context and prior knowledge without the interference of years of practice-this is new. Games accelerate learning by reducing the some of the gatekeeping issues. Now a person without the strength, dexterity and madness can share in some of the experience of riding skateboard off a ramp.  The benefit of games may be in the increased richness of a virtual interactive experience,  and provide the immediate task competencies without the time required to become competent. Games provide a protocol, expedite, and scalffold players toward a fidelity of conceptual experience.

For example, in RIDE, the player is immediately able to do tricks that require many years of practice because the game exaggerates the fidelity of experience. Â This cuts the time it might take to develop conceptual knowledge but reducing the the necessity of coordination, balance, dexterity and insanity to ride a skateboard up a ramp and do a trick in the air and then land unscathed.

Gameficators might embrace this notion.

Games can enhance learning in a classroom, and enhance what is already called experiential learning.

My point:

words, terms, concepts, and domain praxis matter.

Additionally, we seem to be missing the BIG IDEA:

- that the way we structure problems is likely predictive of a successful solutionHerb Simon expressed the idea in his book The Sciences of the Artificial this way:

“solving a problem simply means representing it so as to make the solution transparent.” (1981: p. 153)

Games can help structure problems.

But do they help learners understand how to structure a problem. Do they deliver conceptualized knowledge? Common vocabulary indicative of a content domain?

The issue is really about What Games are Good at Doing, not whether they are better than some other traditional form of instruction.

Do they help us learn how to learn? Do they lead to crystallized conceptual knowledge that is found in the use of common vocabulary? In physics class, when we mention “resistance”, students should offer more than

“Resistance is futile”

or, a correct but non-applicable answer such as “an unwillingness to comply”.

The key is that the student can express the expected knowledge of the content domain in relation to the word. This is often what we test for. So how do games lead to this outcome?

I am not hear to give gameficators a hard time–I have a gamefication badge (self-created)–but I would like to know that when my learning is gamefied that the gameficator had some knowledge from the last century of instructional design and learning research, just as I want my physics student to know that resistance as an operationalized concept in science, not a popular cultural saying from the BORG.

The concerns expressed here are applicable in most learning contexts. But if we are going to advocate the use games, then perhaps we should look at how good games are effective, as well as how good lessons are structured. Perhaps more importantly,

- we may need to examine our prevalent misunderstandings about learning assessment;

- perhaps explore the big ideas and lessons that come from years educational psychology research, rather than just renaming and creating new platform without realizing or acknowledging, that current ideas in gamefication stand on the established shoulders of giants from a century of educational research.

Jargonification is a big concern. So lets make our words matter and also look back as we look forward. Games are potentially powerful tools for learning, but not all may be effective in every purpose or context. What does the research say?

I am hopeful gamefication delivers a closer look at how game-like instructional design may enhance successful learning.

I don’t think anyone would disagree — fostering creativity should be a goal of classroom learning.

However, the terms creativity and innovation are often misused. When used they typically imply that REAL learning cannot be measured. Fortunately, we know A LOT about learning and how it happens now. It is measurable and we can design learning environments that promote it. It is the same with creativity as with intelligence–we can promote growth in creativity and intelligence through creative approaches to pedagogy and assessment. Because data-driven instruction does not kill creativity, it should promote it.

One of the ways we might look at creativity and innovation is through the much maligned tradition of intelligence testing as described in the Wikipedia:

Fluid intelligence or fluid reasoning is the capacity to think logically and solve problems in novel situations, independent of acquired knowledge. It is the ability to analyze novel problems, identify patterns and relationships that underpin these problems and the extrapolation of these using logic. It is necessary for all logical problem solving, especially scientific, mathematical and technical problem solving. Fluid reasoning includes inductive reasoning and deductive reasoning, and is predictive of creativity and innovation.

Crystallized intelligence is indicated by a person’s depth and breadth of general knowledge, vocabulary, and the ability to reason using words and numbers. It is the product of educational and cultural experience in interaction with fluid intelligence and also predicts creativity and innovation.

The Myth of Opposites

Creativity and intelligence are not opposites. It takes both for innovation.

What we often lack are creative ways of measuring learning growth in assessments. When we choose to measure growth in summative evaluations and worksheets over and over , we nurture boredom and kill creativity.

To foster creativity, we need to adopt and implement pedagogy and curriculum that promotes creative problems solving, and also provides criteria that can measure creative problem solving.

What is needed are ways to help students learn content in creative ways through the use of creative assessments.

We often confuse the idea of  learning creatively with trial and error and play, free of any kind of assessment–that somehow the Mona Lisa was created through just free play and doodling. That somehow assessment kills creativity.  Assessment provide learning goals.

Without learning criteria, students are left to make sense of the problem put before them with questions like “what do I do now?” (ad infinitum).

The role of the educator is to design problems so that the solution becomes transparent. This is done through providing information about process, outcome, and quality criteria . . . assessment, is how it is to be judged. For example, “for your next assignment, I want a boat that is beautiful and  that is really fast. Here are some examples of boats that are really fast.  Look at the hull, the materials they are made with, etc. and design me a boat that goes very fast and tell me why it goes fast. Tell me why it is beautiful.” Now use the terms from the criteria. What is beautiful? Are you going to define it? How about fast? Fast compared to what? These open-ended, interest-driven, free play assignments might be motivating, but they lead to quick frustration and lots of “what do I do now?”

But play and self-interest arte not the problem here. The problem is the way we are approaching assessment.

Although play is described as a range of voluntary, intrinsically motivated activities normally associated with recreational pleasure and enjoyment; Pleasure and enjoyment still come from judgements about one’s work–just like assessment–whether finger painting or creating a differential equation. The key feature here is that play seems to involve self-evaluation and discovery of key concepts and patterns. Assessments can be constructed to scaffold and extend this, and this same process can be structured in classrooms through assessment criteria.

Every kind of creative play activity has evaluation and self-judgement: the individual is making judgements about pleasure, and often why it is pleasurable. This is often because they want to replicate this pleasure in the future, and oddly enough, learning is pleasurable. So when we teach a pleasurable activity, the learning may be pleasurable. This means chunking the learning and concepts into larger meaning units such as complex terms and concepts, which represent ideas, patterns, objects, and qualities. Thus, crystallized intelligence can be constructed through play as long as the play experience is linked and connected to help the learner to define and comprehend the terms (assessment criteria). So when the learner talks about their boat, perhaps they should be asked to sketch it first, and then use specific terms to explain their design:

Bow is the frontmost part of the hull

Stern is the rear-most part of the hull

Port is the left side of the boat when facing the Bow

Starboard is the right side of the boat when facing the Bow

Waterline is an imaginary line circumscribing the hull that matches the surface of the water when the hull is not moving.

Midships is the midpoint of the LWL (see below). It is half-way from the forwardmost point on the waterline to the rear-most point on the waterline.

Baseline an imaginary reference line used to measure vertical distances from. It is usually located at the bottom of the hull

Along with the learning activity and targeted learning criteria and content, the student should be asked a guiding question to help structure their description.

So, how do these parts affect the performance of the whole?

Additionally, the learner should be adopting the language (criteria) from the rubric to build comprehension. Taking perception, experience, similarities and contrasts to understand Bow and Stern, or even Beauty.

Experiential Learning for Fluidity and Crystallization

What the tradition of intelligence offers is an insight as to how an educator might support students. What we know is that intelligence is not innate. It can change through learning opportunities. The goal of the teacher should be to provide experiential learning that extends Fluid Intelligence, through developing problem solving, and link this process to crystallized concepts in vocabulary terms that encapsulate complex process, ideas, and description.

The real technology in a 21st Century Classroom is in the presentation and collection of information. It is the art of designing assessment for data-driven decision making. The role of the teacher should be in grounding crystallized academic concepts in experiential learning with assessments the provide structure for creative problem solving. The teacher creates assessments where the learning is the assessment. The learner is scaffolded through the activity with guidance of assessment criteria.

A rubric, which provides criteria for quality and excellence can scaffold creativity innovation, and content learning simultaneously. A well-conceived assessment guides students to understand descriptions of quality and help students to understand crystallized concepts.

An example of a criteria-driven assessment looks like this:

| Purpose & Plan | Isometric Sketch | Vocabulary | Explanation | |

| Level up | Has identified event and hull design with reasoning for appropriateness. | Has drawn a sketch where length, width, and height are represented by lines 120 degrees apart, with all measurements in the same scale. | Understanding is clear from the use of five key terms from the word wall to describe how and why the boat hull design will be successful for the chosen event. | Clear connection between the hull design, event, sketch, and important terms from word wall and next steps for building a prototype and testing. |

| Approaching | Has chosen a hull that is appropriate for event but cannot connect the two. | Has drawn Has drawn a sketch where length, width, and height are represented. | Uses five key terms but struggles to demonstrate understanding of the terms in usage. | Describes design elements, but cannot make the connection of how they work together. |

| Do it again | Has chosen a hull design but it may not be appropriate for the event. | Has drawn a sketch but it does not have length, width, and height represented. | Does not use five terms from word wall. | Struggles to make a clear connection between design conceptual design stage elements. |

What is important about this rubric is that it guides the learner in understanding quality and assessment. It also familiarizes the learner with key crystallized concepts as part of the assessment descriptions. In order to be successful in this playful, experiential activity (boat building),  the learner must learn to comprehend and demonstrate knowledge of the vocabulary scattered throughout the rubric such as: isometric, reasoning, etc. This connection to complex terminology grounded with experience is what builds knowledge and competence. When an educator can coach a student connecting their experiential learning with the assessment criteria, they construct crystallized intelligence through grounding the concept in experiential learning, and potentially expand fluid intelligence through awareness of new patterns in form and structure.

Play is Learning, Learning is Measurable

Just because someone plays, or explores does not mean this learning is immeasurable. The truth is, research on creative breakthroughs demonstrate that authors of great innovation learned through years of dedicated practice and were often judged, assessed, and evaluated.  This feedback from their teachers led them to new understanding and new heights. Great innovators often developed crystallized concepts that resulted from experience in developing fluid intelligence. This can come from copying the genius of others by replicating their breakthroughs; it comes from repetition and making basic skills automatic, so that they could explore the larger patterns resulting from their actions. It was the result of repetition and exploration, where they could reason, experiment, and experience without thinking about the mechanics of their actions.  This meant learning the content and skills from the knowledge domain and developing some level of automaticity. What sets an innovator apart it seems, is tenacity and being playful in their work, and working hard at their play.

According to Thomas Edison:

During all those years of experimentation and research, I never once made a discovery. All my work was deductive, and the results I achieved were those of invention, pure and simple. I would construct a theory and work on its lines until I found it was untenable. Then it would be discarded at once and another theory evolved. This was the only possible way for me to work out the problem. … I speak without exaggeration when I say that I have constructed 3,000 different theories in connection with the electric light, each one of them reasonable and apparently likely to be true. Yet only in two cases did my experiments prove the truth of my theory. My chief difficulty was in constructing the carbon filament. . . . Every quarter of the globe was ransacked by my agents, and all sorts of the queerest materials used, until finally the shred of bamboo, now utilized by us, was settled upon.

On his years of research in developing the electric light bulb, as quoted in “Talks with Edison” by George Parsons Lathrop in Harpers magazine, Vol. 80 (February 1890), p. 425

So when we encourage kids to be creative, we must also understand the importance of all the content and practice necessary to creatively breakthrough. Edison was taught how to be methodical, critical, and observant. He understood the known patterns and made variations. It is important to know the known forms to know the importance of breaking forms. This may inv0lve copying someone else’s design or ideas. Thomas Edison also speaks to this when he said:

Everyone steals in commerce and industry. I have stolen a lot myself. But at least I know how to steal.

Edison stole ideas from others, (just as Watson and Crick were accused of doing). The point Watson seems to be making here is that he knew how to steal, meaning, he saw how the parts fit together. He may have taken ideas from a variety of places, but he had the knowledge, skill, and vision to put them together. This synthesis of ideas took awareness of the problem, the outcome, and how things might work. Lots and lots of experience and practice.

To attain this level of knowledge and experience, perhaps stealing ideas, or copying and imitation are not a bad idea for classroom learning? However copying someone else in school is viewed as cheating rather than a starting point. Perhaps instead, we can take the criteria of examples and design classroom problems in ways that allow discovery and the replication of prior findings (the basis of scientific laws). It is often said that imitation is the greatest form of flattery. Imitation is also one of the ways we learn. In the tradition of play research, mimesis is imitation–Aristotle held that it was “simulated representation”.

The Role of Play and Games

In close, my hope is that we not use the terms “creativity” and “innovation” as suitcase words to diminish such things as minimum standards. We need minimum standards.

But when we talk about teaching for creativity and innovation, where we need to start is the way that we gather data for assessment. Often assessments are unimaginative in themselves. They are applied in ways that distract from learning, because they have become the learning. One of the worst outcomes of this practice is that students believe that they are knowledgeable after passing a minimum standards test. This is the soft-bigotry of low expectation. Assessment should be adaptive, criteria driven, and modeled as a continuous improvement cycle.

This does not mean that we must  drill and kill kids in grinding mindless repetition. Kids will grind towards a larger goal where they are offered feedback on their progress. They do it in games.

Games are structured forms of play. They are criteria driven, and by their very nature, games assess, measure, and evaluate. But they are only as good as their assessment criteria.

These concepts should be embedded in creative active inquiry that will allow the student to embody their learning and memory. However, many of the creative, inquiry-based lessons I have observed tend to ignore the focus of academic language–the crystallized concepts. Such as, “what is fast?”, “what is beauty”, Â “what is balance?”, or “what is conflict?” The focus seems to be on interacting with content rather than building and chunking the concepts with experience. When Plato describes the world of forms, and wants us to understand the essence of the chair, i.e., “what is chairness?” We may have to look at a lot of chairs to understand chairness. Â Bu this is how we build conceptual knowledge, and should be considered when constructing curriculum and assessment. A guiding curricular question should be:

How does the experience inform the concepts in the lesson?

There is a way to use data-driven instruction in very creative lessons, just like the very unimaginative drill and kill approach. Teachers and assessment coordinators need to take the leap and learn to use data collection in creative ways in constructive assignments that promote experiential learning with crystallized academic concepts.

If you have kids make a diorama of a story, have them use the concepts that are part of the standards and testing: Plot, Character, Theme, Setting, ETC. Make them demonstrate and explain. If you want kids to learn the physics have them make a boat and connect the terms through discovery. Use their inductive learning and guide them to conceptual understanding.This can be done through the use of informative assessments, such as with rubrics and scales for assessment.  Evaluation and creativity are not contradictory or mutually exclusive. These seeming opposites are complementary, and can be achieved through embedding the crystallized, higher order concepts into meaningful work.

The work I have done surrounding games has led to improvement in reading scores. In 2006-2007, I took over the Language Arts Instruction for an entire middle school in Minneapolis, MN. The students were primarily drawn from North Minneapolis, qualified for free and reduced lunch, and were very bright, but were not scoring well on the standardized assessments. I implemented a curriculum that studied video games as new forms of narrative. Games tell stories, just like the anthologies stacked on my shelves. The difference was that when I pulled out the anthologies, classroom management became more challenging, as most of the kids were willing to get a behavioral referral than sit through a reading of “The Treasure of Lemon Brown” from the anthology.

The work I have done surrounding games has led to improvement in reading scores. In 2006-2007, I took over the Language Arts Instruction for an entire middle school in Minneapolis, MN. The students were primarily drawn from North Minneapolis, qualified for free and reduced lunch, and were very bright, but were not scoring well on the standardized assessments. I implemented a curriculum that studied video games as new forms of narrative. Games tell stories, just like the anthologies stacked on my shelves. The difference was that when I pulled out the anthologies, classroom management became more challenging, as most of the kids were willing to get a behavioral referral than sit through a reading of “The Treasure of Lemon Brown” from the anthology.

These referrals were a lot of work, and there is no academic learning happening during that process.

I decided that instead of pushing stories at them, I should ask them what kind of media they liked. Most of them told me that they played video games and liked television, but few if any had any idea that there was anything of value in games besides entertainment. My role was to get them to understand literary elements, genre patterns, and critical thinking–the things being tested in the new standardized tests! The games provided an easy entry into narrative fiction, with the opportunity to also discuss genre and film techniques, as well as interaction and games studies.

Often people assume that kids are naturally good at games. That because they are young, that children are digital natives, and can comprehend and problem solves like secret genius in the wilds away from the classroom. Surprisingly, most kids are not fluent in how games work, they struggle with in-game problem solving, and they are often limited in discussing how games work. Surprised? One would have thought there would be an easy transfer of learning from games to books. But it was just not so.

There was no hidden genius here–many of the kids knew all about games, but few actually played them. Is this a digital native? When we use that term, we assume that these kids have great knowledge and critical thinking skills because of video games and television, and if we could only tap into them, they would show us the expertise we hoped was there with digital media, where they lacked with printed text. This was also found in a previous study.

Disappointing as that can be, games do offer a high interest, and more accessible narrative. I decided to use this opportunity to use their interest in games to develop their potential genius in books. Games provide interaction, social capital, and complex situations that kids can describe when taught to compose walkthroughs and multimedia book reports. The video games are actually were more accessible to kids: they have the same literary patterns, but the kids don’t have to take the step of decoding the words. This means we can practice literary elements with more accessible text. And I don’t mean infantilized “readability” accessible. I mean that the students were interacting with age appropriate, high interest, complex stories, and getting feedback as part of the game play. They could play and discuss, and build their awareness of the story, just like we do with reading circles.

The intent was to study games like we would study a printed text. Many of the students were game players, but few were very successful game players. This 9 week unit was well-received, as many of the students were interested in learning more about games, getting better at them, and doing something we did not ordinarily get to do in a classroom.

The difficulty that I was facing came from cultural beliefs about games. Many believe that games are devoid of learning and academic uses. This was especially true for many of my colleagues. They had the feeling that kids were just participating with weapons of mass distraction, and there would be a debt to pay on the upcoming state MCA2 reading test. For this reason, I made sure I educated my administrators, Milken TAP observers, and parents after I had done my planning. I made sue to invite stakeholders in to my room to observe, evaluate my instruction, and to interview kids and make them justify the unit by asking them direct questions about the value of studying games at school.

The kids did defend the unit, and made sure to back up what they were saying with examples. One student, Tony, when asked what value there was in studying Sonic the Hedghog replied, “you don’t understand, Sonic is just like the Odyssey story, he just wants to get home.”

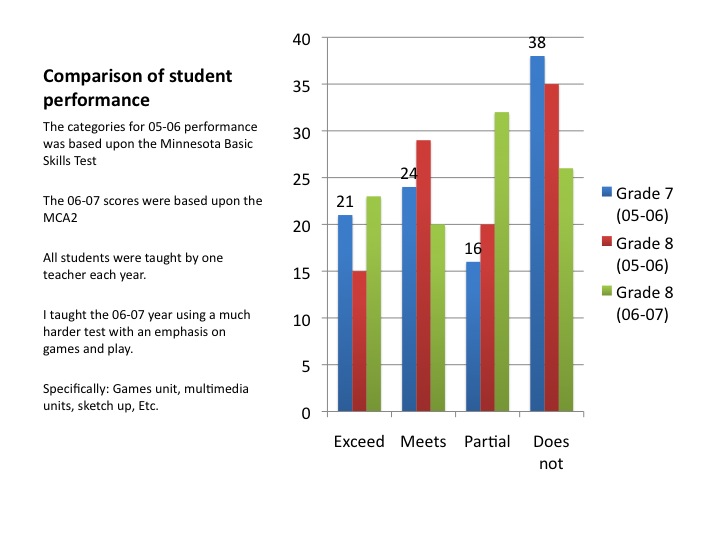

Because a large percentage (38%) of my students were not even close to passing the Minnesota Basic Skills Test, I was questioned about the usefulness of this unit when I should be doing reading drill and practice. However, my administrators thought I had an innovative idea, and parents supported this unit.

So 38% of my eighth-graders had a cut score of 1 on the Minnesota Basic Skills Test (MBST) — a test based upon recall– and we were about to face the Minnesota Comprehension Assessment 2 (MCA2), which is a comprehension assessment based upon genre patterns and literary elements. The standards for reading and literature asked for the students to understand plot, setting, theme, etc. This is not a recall test.

My kids were all bright, but they had disengaged from the testing process, and the preparation for it. Saying something would be on the test was not motivating, but comparing a game title they looked to other texts we read was motivating. Now we were getting the practice necessary for identifying the kind of conceptual information necessary to do well on the MCA2: they began learning literary elements and genre patterns.

I created this curriculum of game study. The organizing principle was that games are new forms of narrative, and that by studying game narratives, I could teach them literary elements and genre patterns. I created rubrics and assignments from the literary elements from the Minnesota state standards and integrated ideas from traditional Language Arts curriculum.

This is what happened:

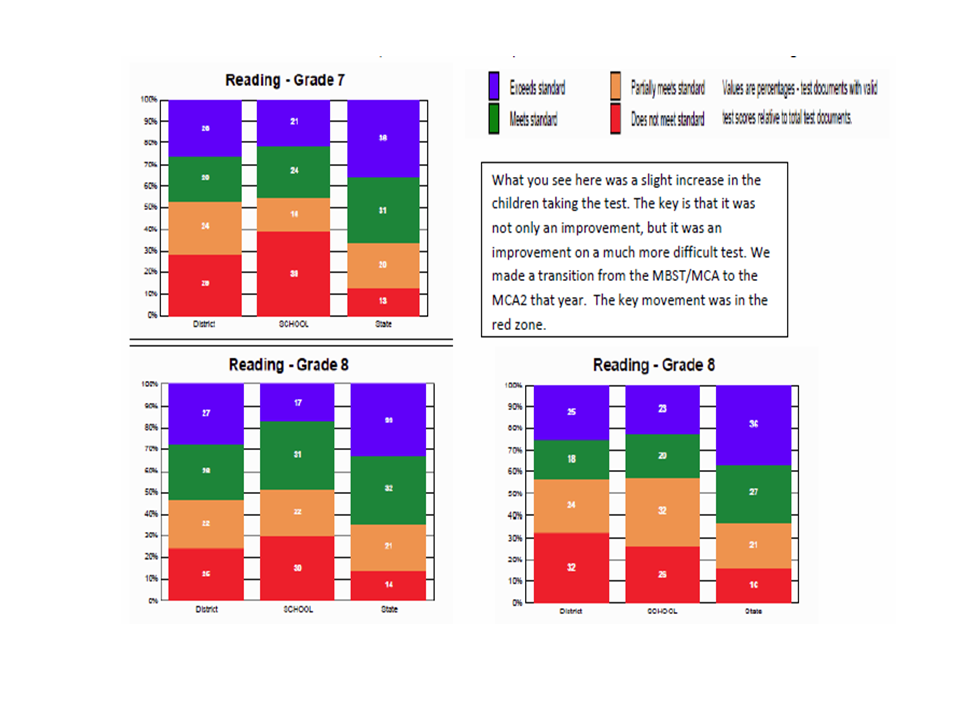

You will notice that between Seventh grade (Blue) and the Eighth grade the following year (Green) there was significant improvement. During that eighth grade year, we had better scores on a harder test. In a year when we switched from the Minnesota Basic Skills Test to the Minnesota Comprehension Assessment to the MCA2, we had significant improvement across the cut scores.

What you see in comparing my eighth-graders (GREEN–took the harder MCA2) with the eighth-graders the year before (RED — took the MBS) was that there was a significant difference in achievement differences in the bottom performers. There were significantly fewer in the bottom cut score: a 9% movement out of “Does Not Meet”.

When comparing tmy students 05-06 seventh-grade students their scores as eighth-graders, there was a 12% improvement.

Not only was there improved test performance, but I was seeing my students return to school, and showing improved performance in the classroom, and on the test. The return of these kids was very satisfying and I had fun teaching the unit. What was great was the change in the learning culture. The kids really valued the time we spent and professed that they were learning. But it was also satisfying to see an increase in the amount of students who met or exceeded the higher standard.

The unit was not easy, but the students had something interesting and more concrete to apply the concepts I want them to learn. Remember, I built my games unit on the standards. Games are another narrative. They have all the same literary elements and genre patterns. My students were basically doing a technical writing assignment in the form of a multimedia book report.

The bottom line, they surpassed expectations on the more difficult MCA2 test. We were expected to go down 12%. We went completely the other way.

We did do complementary readings, like The Odyssey, Raisin in the Sun, Sonny’s Blues, Langston Hughes, and more. The key element was that the kids now had a portal into these other areas. The video games unit gave them success, and showed them they could do it. A big part of this was the creation of meaningful rubrics, and my taking a role as facilitator rather than know-it-all. I could ask, I could use the language of the rubrics like roadmaps for assessments.

But the learning did not stop there. The kids opened to the learning,and the became willing to open the books. And I know it worked. We were taken on a field trip to the Guthrie Theater, and on our tour, we were taken under the stage. The docent told us that where we were under the stage was called “the underworld”. The kids ALL looked at me, and said, “is this why you brought us here? Just like in the Odyssey?”

I said, “of course, yeah!” not having any idea, and we laughed.

We had practiced using the abstract concepts like literary elements and genre patterns with more accessible narratives (games), and applied what we learned about game studies to talk about literature. We used game studies to leverage printed text. Stanovich calls this compensation–warming up cognitive cold spots with warm ones.

This unit valorized activities that kids choose and participate in outside of school. It created a situation where kids who were often not high achievers, but were smart and understood the games, could now take leadership, and use their prior knowledge and experience with games, and help classmates. This was a win-win for developing academic skills, and life skills.

Central to the student’s success was that the instruction and assessment were grounded with an empirical model of reading comprehension, which viewed comprehension as the construction of mental representation. The better kids are at creating mental representation, the better they will be at questions and problem solving.

Once students can visualize and create mental representation, the can reflect upon the story and begin to apply the literary concepts and genre patterns. This was easier with games because they did not have to learn from a text, and get to the content through decoding symbols into meaning. When they payed a game, they saw and experienced, and could conceptualize from what Piaget called Image Schemas–mental representations from the senses, and learn the characteristics of the literary terms in the context of the things they were abstracted from.

What many kids who struggle with reading face is not cognitive deficits, but a poverty of experience, and thus experience with the world to attach to the words and concepts we want them to learn. If you don’t know about music, reading about it will not give you a personal, or deep understanding. You may understand in theory, by learning one abstraction by connecting it to another–but this is wholly different than having experience to develop concepts through induction, rather than deduction.

But that is often what we do in the classroom. Present the abstract concept, and ask them to learn in by reading–another abstract process dependent upon decoding and translating symbols into mental images. This seems backwards. Imagine a child who has never seen a peach, or known anything about peaches trying to decode, “he lifted the peach to his mouth and was surprised to be tickled as he took a bite.”

Without prior knowledge and experience, the child cannot know about peach fur. Would you imagine arms and tickling fingers?

Games and objects ground instruction, and provide the basis for experience and mental representation — comprehension. When we have this, we can spend less time decoding and more time discussing printed text. So by writing about accessible narratives such as games, we were more successful when reading related printed text. We had learned process, concepts, and deconstructing problems. This led to huge changes in student academic performance and confidence.

The majority of my curriculum that year was in studying video games as new narratives.

Here is the curriculum

Here is a story about what we were doing

Here is a class you can take I have been offering for the last seven years. You can take it online here at Professional Learning Board.

There is a lot to learn in a game, but there is a whole lot more to learn outside of the game in documenting, listening, presenting ideas, and extending them, than just playing the games themselves.

If you want, there is a whole bunch of games curriculum on my teaching blog for language arts, reading, engineering, computer science, etc.

Everything from board games to curriculum for analysis of a time line. You might notice that they are set up to be run like a game.

I am hoping that this article makes a start for teachers embracing a model where they consider Learning by Design.Interestingly, games are also involved in assessment, and kids like to know their scores. The scores are an indication of learning.

And the learning is the fun part, the content and the problems are hard and learning is not always easy, but it can be desirable. Games are hard too, oddly enough, but when enough kids play them, and it creates enough buzz as social capital, there will be interest and some sacrifice to try and persevere in learning.

Tenacity, and metacognition are learned traits. With games and play, we can teach them.

What I like about what Katy did with this article is that she showed games in the classroom that do not have to pivot on the “digital natives” argument.

Kids like games, not all of them, but many kids are interested — it really does take a facilitator to motivate people and to create transfer to academic “work” or formal learning even if there is a high-interest activity available.

Teachers are important to practice and modeling to create a successful habit of learning the process of creating transfer.

That is, the kids need to learn how to learn, and think about learning.

This is called metacognition.

We all need to learn to question quality, question, raise and praise standards, be particular, and really think through the cognitive, social and cultural processes of comparison, combination, contrast, and reduction.

Learning by Design

The curriculum surrounding the games must be designed like a game in many ways:

- the directions are clear;

- everyone knows they can win;

- they can win in different ways;

- there are support and resources;

- there is clear criteria in the signal words for qualities and process.

What is the difference between learning with games and learning with text books?

Play as the learning mood (subjunctive mood) and therefore the social structures surrounding the games.

Also, kids have the ownership, and this puts the teacher in the role of facilitator who must be accepting of guiding the learner though the criteria–so if you have lousy criteria, and are not consistent with what your signal words mean in quality and process, expect lousy work, if not riots.

But if you put forward bad games, no curriculum or bad learning objectives, it is just like reading out of those boring collections of literature texts, without merit, and without no street cred.

The games are not the technology, the curriculum design surrounding the games are the technology. The computers only mediate good instructional design that teachers have always done in cooperative learning– and this exists in board games as well as it has in apprenticeship organizations to learn trades– just like it does in live action role plays, that in some genres, are what evolved into video games.

Good instruction is just good instruction. Hopefully this article takes folks towards that direction.

Because we can take the games and go a little further than merely connect.

Just playing a game may increase some cognitive functioning in low functioning people, but that does not mean that they can take that increase in in-game problem solving to in-life problem solving.

Being good at the game does not mean you will pass a reading test.

Does the reading test really matter?

Maybe not.

Should they be able to pass it?

Yes. They are not that hard.

The work I have done surrounding games has led to improvement in reading scores.

You will notice that between Seventh grade (top-left) and the Eighth grade the following year (bottom-right) there was significant improvement in the school column. During that eighth grade year, I had all of the eighth -graders–but more importantly, we had a significant gain in a year when we switched from the Minnesota Basic Skills Test/ Minnesota Comprehension Assessment to the MCA2, which is a significantly harder test. What you see in comparing my eighth-graders with the year before was the movement from the bottom (who are the hardest to move btw) , the increase in students taking the test (they were all coming to class because of the curriculum), and the amount of students who met or exceeded a higher standard. I must admit, I built my games unit on the standards and my background in reading comprehension made games an easy connection — games are another narrative with all the same literary elements and genre patterns.

You will notice that between Seventh grade (top-left) and the Eighth grade the following year (bottom-right) there was significant improvement in the school column. During that eighth grade year, I had all of the eighth -graders–but more importantly, we had a significant gain in a year when we switched from the Minnesota Basic Skills Test/ Minnesota Comprehension Assessment to the MCA2, which is a significantly harder test. What you see in comparing my eighth-graders with the year before was the movement from the bottom (who are the hardest to move btw) , the increase in students taking the test (they were all coming to class because of the curriculum), and the amount of students who met or exceeded a higher standard. I must admit, I built my games unit on the standards and my background in reading comprehension made games an easy connection — games are another narrative with all the same literary elements and genre patterns.

The bottom line, they surpassed expectations. We were expected to go down 12%.

The majority of my curriculum that year was in studying video games as new narratives.

Here is the curriculum

Here is a story about what we were doing

Here is a class you can take I have been offering for the last seven years

There is a lot to learn in a game, but there is a whole lot more to learn outside of the game in documenting, listening, presenting ideas, and extending them, than just playing the games themselves.

If you want, there is a whole bunch of games curriculum on my teaching blog for language arts, reading, engineering, computer science, etc.

Everything from board games to curriculum for analysis of a time line. You might notice that they are set up to be run like a game.

I am hoping that this article makes a start for teachers embracing a model where they consider Learning by Design.Interestingly, games are also involved in assessment, and kids like to know their scores. The scores are an indication of learning.

And the learning is the fun part, the content and the problems are hard–and learning is not always easy, but it can be desirable. Games are hard too, oddly enough, but when enough kids play them, and it creates enough buzz as social capital, there will be interest and some sacrifice to try and persevere in learning.

Tenacity and metacognition are learned traits. With games and play, we can teach them.