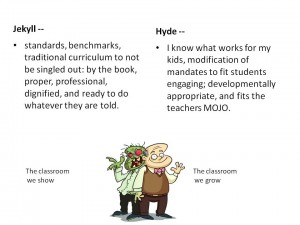

The Jekyll and Hyde Effect calls into question approaches to accountability and implementation of mandated approaches to research-validated techniques and assessment in classroom instruction. Dissonance between teachers core beliefs about student learning and these new mandates, as presented to them, may be creating two different identities, two different classrooms, and two different sets of books to satisfy mandates and continue doing what they know works. This study utilized discourse analysis, coding teacher artifacts as outcomes of genre chains with themes from mandates, policy, and law for classroom changes in curriculum and instructional assessment tools, materials, and professional development. The informants from the studies and findings from analysis of the artifacts reveal that many teachers do not feel that what is good for the spreadsheet is good for kids. This tension in core beliefs about learning and instruction need not lead to conflict– integration of assessment and appropriate implementation could enhance teacher and student experience. The transformation of policy to implementation was seen as problematic and led to misunderstanding and conflict, often based upon an inability to see standards, benchmarks, and assessments integrated into engaging, play-like activities such as games rather than the controlled, direct instruction that might cause resistance and disinterest by students and instructors, but easy to identify by administrators. The presentation makes a case for the importance of play in engagement and comprehension through review of literature on intelligence measures and new research on embodiment theory and the indexical hypothesis. Then it give examples of implementation.

New models of comprehension and memory validate the value of active and playful learning for cognitive enhancement and generative transfer. Data on academic performance and engagement measures from five years of games, play, and virtual space learning in K-20 classrooms will be presented in the context of assessment measures using a model for assessing cognitive growth. This is contrasted with educator beliefs, the efficacy of play, and the limitations of models of teacher professionalism creating a Jekyll and Hyde Effect. Though interviews, artifacts, and surveys, K-20 educators have expressed a willingness to embrace games, but have been reluctant to do so publicly for fear of professional reputation, as well as the ability to implement such pedagogical change.

In this presentation, on overview of research, methodology, outcomes, and descriptions of implementation will be presented on how video games and virtual worlds were used to raise standardized reading scores. This evidence, methodology, and experience is presented with outcomes of surveys, interviews, and discourse analysis of teacher artifacts, and presents the institutional experiences of educators balancing the tension of using games and play, and the fear of being stigmatized as unprofessional at their teaching sites. The result begins to create a picture of creating two different sets of books, and two different teaching identities — Jeckyll and Hyde.

Schools Get in the Game

Ok, it’s time to submit your school reports. Did everyone play Mario Kart at the weekend? Good. Let’s begin with group discussion, what is the games premise and objective?

This may sound a little strange but for one Minneapolis teacher video games have become learning tools for his class of sixth to eighth graders. Brock Dubbels of Seward Montessori in Minneapolis designed his ‘Video Games as Learning Tools’ class to span a three week period. Requiring children to create detailed multimedia presentations from video games played in groups. He explains that the children are not just learning from the games content but also gaining key skills from playing and studying the games. Dubbels, who has a background in cognitive psychology, goes on to say “It connects to their lives, research shows that children want to perform where they have competence.†Brock Dubbels will be spreading the word throughout the summer period with training seminars and online courses designed to show other teachers how his three week course works.

The children split up into groups and play video games. They will take notes whilst playing, with the goal being to explain how the game is played, how a player might win and how the game is designed. It is said to be a modern version of a book report. But is this new take on the rising popularity of video games a healthy and positive attitude? Or will it just teach children that they can just goof around playing video games and call it learning?

This course is an online introduction to Video Games as Learning Tools, a comprehensive course based upon five years of implementation and research. The course builds from three concepts:

- Deep Learning

- Games

- Motivation

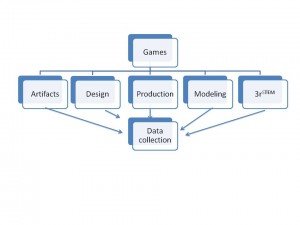

The course offers innovative ways to learn and connect engaging instructional strategies, research, and resources for educators, instructional designers, game makers, and people with an interest in games and learning. The course is built from an instructional framework that lists five ways that games can be used for instruction (figure 1).

The course provides an overview of games, and how they can be used as:

- artifacts and texts for study and instruction

- as guidelines for designing instruction (to utilize game design concepts for classrooms, training, and professional development), as well as curriculum tools for content delivery.

- as a means for producing new media and new narratives such as machinima, modding (modifying of the shelf games into new games.

- as models, representation, simulations, and the study of virtual worlds

- and as a portal to developing 3rSTEM, an approach for teaching reading, writing, SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, ENGINEERING, and MATHEMATICS

This framework is intended to offer a range of experiences for a variety of learners and familiarity with games, as well as purposes and objectives. The introductory course offers beginners a range of experiences for developing comfort and competence, as well as approaches to using games for instructional purposes, and it offers game enthusiasts and game designers opportunity to gain introduction to research, learning theories, and design techniques.

The course was designed to be self-paced, allow the learner choice and opportunity to choose outcomes and learning purpose, and provide resources and community.

The course has been offered for four years at the University of Minnesota graduate school in the College of Education and Human Development, and embodies accessibility and quality.

Take a look at some comments and recommendations on my Linked in page

The course is available online through the Professional Learning Board in conjunction with Minneapolis Public Schools Alternative Teacher Professional Pay System and the University of Minnesota.

Sign up by clicking the space invader.

Video Games as Learning Tools

Video Games as Learning Tools

Students interested in graduate credits may purchase three 5000 level graduate credits for half the normal price.

If you email the instructor, coupon codes are available for Minneapolis Public School Teachers and the first 10 Non-MPS students

Why is learning and instruction so severe?

Why is learning and instruction so severe?

Why is it that we say ” there is no time for playing here . . . don’t , mess around”.

Should games and play be considered important in designing instructional contexts?

We do know that play is important in the early development of children, but we soon change from the natural learning state of the learner to the convenience of the instructor. This may have come about from a number of factors, but it is likely an issue of convenience for the instructor, not the instructed.

Games and play may offer a more fertile approach for designing instruction, where individuals can be put into a learning environment rich with choice and feedback . . . not only for gathering information about a student’s learning, but that also demand mastery, plenty of do-overs, and where the performance is the assessment (informative assessment — not assessment where the learner is sequestered from learning for the sake of testing in a non-learning situation!). Games and play, by their very nature, assess, measure, and evaluate — and good games and curriculum built upon the principals of play do it in a way that is a seamless and an integrated part of the story arc, and the assessments are the performance ( you do it, or you do it over . . . . and you should wanna do it).

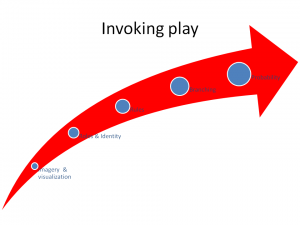

The taxonomy (above) comes from Dubbels (2008), where observations in game play were coded from this model for research on reading comprehension and game play.

The model was developed by looking at games as a structured form of play, where learning was considered as one of the primary purposes of play, and that learning really is our natural state.

We are always learning; sometimes we are learning that we do not like what we are being asked to learn and become– Play is generally though of as intrinsically motivated behavior based upon interest and purpose, as opposed to most formal learning environments.

In this taxonomy, and perhaps it is more a framework than a taxonomy since not all parts need always be present; But each step represents a level of complexity and structure until elements of purposeless free-play has become a structured pursuit in rule-based environments where probability and hypothesis testing are “the play”.

This taxonomy is not all about video games. This taxonomy is an attempt to utilize research on play, as discussed in Play is how we learn.

- The first category: Visualization/ imagination seems primitive, but it can be very sophisticated. It may include driving an imaginary car, or even the basis for proposing a new theory for science much like Einsteins thought experiment about relativity and the speed of light. This can be very effective in getting commitment and motivation in learning and instruction. Use the words imagine and visulaize to start the activity. Games do this well, where we are asked to suspend disbelief and create a situatoin and scenario and our place in it.

- Roles / Identity where the individual may take on the role of a race car driver or a medical doctor. This may include what Williamson Shaeffer calls the epistemic frame, where the semiotic domains (Gee, 2001) identify the individual as part of a group who have an affinity for an activity. In this case the individual may wear a costume, use language, and tools that are particular to this community of practice, where individuals may gather to develop Self-Determination, i.e. skills, relationships, and autonomy.

- Rules are where play becomes more structured, game-like, and more directed, and allows for the semiotic domains to become crystallized as institutionalized discourse, and becomes cultural hegemony, where roles and rules become part of the value system and social hierarchy. An example of this might be, “I am the mommy and you are the baby, so you need to listen to me and do what I say”.

- Branching is where there are a number of possibilities based upon context and situation. Often games have different paths for play where there may be a number of different ways to start the game and move through the game– whether it be through the role of dice, scenarios, and spinners. Think of monopoly and chutes and ladders (snakes and ladders), where there are spaces that are moved through or across that create different situations for success or setbacks.

- Probability/ Estimation involves the likelihood that if this is done, this will happen. By nature, we are calculating and estimate possibility based upon our actions and the actions of others.In a computer game or a live action role play like Dungeons and Dragons, where characteristics may have a quantitative value in proportion to a discrete category, i.e. someone may have an Intelligence of 16 out of 20, and the player must role a 20 sided dice to see if their solution solves the problem they face in the problem/play space of the game–if they roll a 17, 18, 19, or 20, their solution fails. This demands the player to build situation models of the action and propose solutions based upon their understanding of the game space scenario and the possible solution paths based upon game character skills and resources. In a computer mediated game like Elder Scrolls Oblivion or Assassins Creed the computer processes likelihoods of success based upon skills accumulated (these are developed withe each in-game success.

Central for consideration here is that learning occurs in play, and play is very engaging and may provide a portal to sustaining activities and developing an approach to activities that are often classified as work. And for many, being told to work inspires resistance, reluctance, and avoidance tactics in mandatory performances and learning environments such as school, employment, and other conscriptive activities.

Play orientation, and play identities may offer a high interest and high motivation approach to learning that may have a greater probability in sustaining and improving practice, and thus play may act as a portal to engagement.

Games are a structured form of play (Dubbels, 2008), and play represents a portal to deeper learning, where play is an inquiry state and affective approach to activity. Brian Sutton-Smith, in the Ambiguity of Play described work and play as ethos that are dependent upon purpose and context–where an activity may be a play activity for some and arduous work for others–it depends upon personal attribution. The key factor seems to be the expectations of pleasure or dread associated with the activity, and tapping into play when designing learning environments may offer significantly greater likelihood for sustained engagement.

Taxonomy from:

Dubbels, B.R. (2008) Video games, reading, and transmedial comprehension. In R. E. Ferdig (Ed.),Reference. Information ScienceHandbook of research on effective electronic gaming in education.

Play as precursor to comprehension

The process of pretense in play can be very powerful, and it may be the factory of our analogical mind. Vygotsky claimed that it is play that begins to offer liberation from constraint– that we dissociate from teh “real world” into the imaginary world of our play.

In a review of studies by Lewin, it was posited that things dictate to a child what they must do: that we are shaped by tools, rules, relations, context and language; it may be situational constraint that creates direction and action based upon motives and perception; and these can be created through environment.

“but in play, things lose their determining force†and the child may understand the constraints of a condition but gain the ability to act independently of what they see—creating new choices. The act of creating the imaginary and otherness may be an early example of creating mental models of the world that will later be used for inference and reasoning in hypothesis testing—decontextualization and abstraction, allowing not only perception of the context, but perception of the situation and the relevance of that situation in a larger context, creating useful action with the act of perception, and also the act of making meaning.

This is such a reversal of the child’s relation to the real, immediate concrete

This is such a reversal of the child’s relation to the real, immediate concrete

situation that it is hard to underestimate the full significance. The child does

not do this all at once because it is terribly difficult for a child to sever a kids-play-as-doctor

thought (the meaning of a word) from an object. . . Play provides a transitional

stage in this direction whenever an object (for example a stick) becomes a

pivot for severing meaning of horse from a real horse. The child cannot yet

detach thought from object. (Vygotsky, 1976, p 97).

Thus play seems essential to development, and the role of the pivot ( a toy, representation, or even a game) is important in aiding that early childhood development, where children may move from recognitive play to symbolic and imaginative play, i.e. the child may play with a phone the way it is supposed to be used to show they can use it (recognitive), and in symbolic or imaginative play, they may pretend a banana is the phone. This is an important step since representation and abstraction are essential in learning language, especially print and alphabetical systems for reading and other discourse. There are as many types of play as there are people and cultures. A few types to consider are:

• Recognitive, or Mastery play – learning how to use objects

• Creative play – playing with aesthetics

• Deep play – learning about risk and danger

• Recapitulative play – den building, hiding, climbing

• Dressing up – experimenting with identity

• Rough and tumble play – testing your own strength

For this reason play and gaming, structured forms of play, may be reasonable predictors for comprehension and problem solving. In play, we create models; try on roles; and experience the world in the safety of play. Play may also expand comprehension in surprising ways, but often activities involving play are seen as non-academic—therefore non-educational, lacking rigor and thus, not really learning (Dubbels, submitted).

This presentation was recently offered at Educational Testing Service to share current research on how games can be used for instructional design, content delivery, and as a means for producing media. Emphasis was placed upon games as new narratives that were used as a means to improving problem solving and comprehension. Central to this approach is the use of the Event Indexing Model, Causal Network analysis for measuring comprehension of the digital narrative, and the important role of play in learning. Subtopics included an instructional design model for uses of games for instruction, the integration of play, and a taxonomy of problem solving. Also mentioned is the role of assessment, especially informative assessment, and examples of how games were used in formal and informal instructional settings