CFP Special Issue On: SURGE, Physics Games, and the Role of Design

Submission Due Date

5/15/2017

Guest Editors

Douglas Clark, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA

Introduction

The purpose of this special issue is to investigate the role of design in the efficacy of physics games in terms of what is learned, by whom, and how. Importantly, studies should move beyond basic media comparisons (e.g., game versus non-game) to instead focus on the role of design and specifics about players’ learning processes. Thus, invoking the terminology proposed by Richard Mayer (2011), the focus should be on value-added and cognitive consequences approaches rather than media comparison approaches. Note that a broad range of research methodologies including a full gamut of qualitative, ethnographic, and microgenetic methodologies are encouraged as well as quantitative and data-mining perspectives. Furthermore, the focal outcomes and design qualities analyzed can span the range of functional, emotional, transformational, and social value elements outlined by Almquist, Senior, and Bloch (2016).

Recommended Topics

Authors are invited to submit manuscripts that

- Focus on the role of design beyond simple medium (i.e., move beyond simple of tests of whether physics games can support learning to instead focus on how the design of the game, learning environment, and social setting influence what is learned, by whom, and how).

- Explore learning in games from the SURGE constellation of physics games and other physics games using qualitative, mixed, design-based research, quantitative, data-mining, or other methodologies.

- Focus on formal, recreational, and/or informal learning settings.

- Focus on any combination of player, student, teacher, designer, and/or any of other participants.

- Answer specific questions such as:

- How do specific approaches to integrating learning constructs from educational psychology (e.g., work examples, signaling, self-explanation) impact the efficacy of these approaches within digital physics games for learning?

- How do elements of design impact the value experienced by players in terms of the elements of functional, emotional, transformational, and social value outlined by Almquist, Senior, and Bloch (2016)?

- What is the role of the teacher in interaction with students and the design of a game in terms of learning outcomes?

- How does game design interact with gender in terms of what is learned, by whom, and how?

- How can designers balance learning goals and game-play goals to best support a diverse range of players and learners?

- How do specific sets of design features interact with players’ learning processes and game-play goals?

Submission Procedure

Potential authors are encouraged to contact Douglas Clark (clark@vanderbilt.edu) to ask about the appropriateness of their topic.

Authors should submit their manuscripts to the submission system using the link at the bottom of the call (Please note authors will need to create a member profile in order to upload a manuscript.).

Manuscripts should be submitted in APA format.

They will typically be 5000-12000 words in length.

Full submission guidelines can be found at: http://www.igi-global.com/publish/contributor-resources/before-you-write/

All submissions and inquiries should be directed to the attention of:

Douglas Clark

Guest Editor

International Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations (IJGCMS)

Email: clark@vanderbilt.edu

Play has been removed from schools by non-educators

Brock Dubbels, Ph.D.

Dept. Psychology, Neuroscience, & Behaviour

McMaster University

It was not psychologists, educators, or child development researchers that removed play from schools. According to McCombs & Miller (2007), the emphasis on performance testing and standardization was led by a campaign of politicians and corporate interests to influence what happened in the classroom. With government reports such as Nation At Risk (1983), the National Governors Association (1989) worked to create Goals 2000 (1994) and called for greater levels of accountability for student achievement and rigorous academic standards. They called for more focus on standardized content, standardized content delivery, and standardized tests. This campaign to standardize schools worked to change classroom curriculum, but it contradicted and ignored 100 years of psychological research about human learning (McCombs & Miller, 2007).

The new standards and assessments became mandated performance indicators on how schools were evaluated. For a school to be rated as competent, their students had to meet federal and state performance guidelines, and school funding was tied to student performance on standardized assessments. This situation became so desperate for some schools, that entire school districts (superintendents, principals, and teachers) committed fraud by falsifying assessment data (Dayen, 2015).

Political reasons for standardization over play

Elected officials and journalists reported that American students had fallen behind other industrialized nations in math and science, and the proof was in American student performance on international testing tests called PISA and TIMMS. They warned that without improvements in student performance in math and science, the USA would no longer be competitive on the world stage (US Committee on Prospering in the Global Economy of the 21st Century, Science, & (US), 2007).

Reports such as these were political in nature. When American student scores are compared to students of the same income level, students in the United States did significantly better than all other countries:

For every administration of PISA and TIMSS, when controlling for

poverty, U.S. public school students are not only competitive, they

downright lead the world. Even at home nationally, when controlling

for poverty, public school students compete with private school

students in Lutheran, Catholic, and Christian schools when analyzing

NAEP data (Ravitch, 2013).

Poverty plays a central role in student performance. Schools serving lower-income students tend to be organized and operated differently than those serving more affluent students. Poverty is the most significant impact on academic performance. It does not matter if these schools are big or small, private, or religious. Poverty is the most significant predictor of poor academic performance (McNeil & Valenzuela, 2000; Rumberger & Palardy, 2005). Students in poverty often come to school without the social and economic benefits held by many middle-to-high SES students, such as access to books, food, parental support with schoolwork, and financial stability (Sirin, 2005).

In wealthy schools, students are more likely experience playful activities and learner centered pedagogy (Anyon, 1980). Schools that serve children in poverty, not only struggle the most, but are also often the first to get the standardized education, reduction in play, and elimination of electives such as music, arts, and training. We may be compounding the problem, rather than offering a solution by removing these things from children in poverty.

Children in poverty also experience greater exposure to threat and violence, which contributes to play deprivation. Play deprivation has arisen as a medical diagnosis. It means that children do not experience the essential cognitive, social, and affective benefits of learning through play (Milteer, Ginsburg, Health, & Mulligan, 2012). Play is an essential element of learning and development. Removing play in favor of standardization is a mistake.

Standardization is profit-centered, not student-centered

If anything was learned from the standardization campaign, it was that the creation of standards and content has proven to be very financially lucrative to testing companies, and very destructive for school districts (Dayen, 2015). These policies have led to change of control, where classrooms are now legislated through national education standards, and this legislation is often influenced, if not written by, lobbyists that work for the companies that profit from selling tests and curriculum, rather than the people who have experience working with children and child development research (Leistyna, 2007).

The shift to standardized assessment and curriculum has also led to instability. It is very profitable to have standards change. When standards change, schools are required to meet those new standards, and this is often accomplished by paying for new tests and new curriculum. State-based initiatives on Common Core—the standards and assessments—change every 4 years (Porter, McMaken, Hwang, & Yang, 2011). Each shift in standards constitutes a form of educational whack-a-mole, where districts are forced to purchase new curriculum, and states must create new assessments. This is a lucrative market, over $2 billion annually (Strauss, 2015).

To cultivate financial opportunity, educational publishers have been very involved in this process; Pearson Education, ETS (Educational Testing Service), Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, and McGraw-Hill collectively spent more than $20 million lobbying in states and on Capitol Hill from 2009 to 2014 (ibid). In many ways, standardization and accountability initiatives have exacerbated the “problems” they set out to solve, and instead, created a lucrative market for pre-packaged curriculum and tests, the deprofessionalization of teachers, and significant cost to American taxpayers.

Standardized methods of assessment often lack the long view, and do not pass the tests of time, retention, and adaptation. According to Atkinson & Mayo, (2010) focus on subject matter and facts only serve to limit student motivation, learning and choice, and reduce the potential for innovation. Additionally, high stakes tests, and the practice of evaluation during instruction is an unreliable index of whether the long-term changes, which constitute learning, have actually taken place (for review, read Soderstrom & Bjork, 2015).

Parents opt-out of standardization

Interestingly, many parents and stakeholders have begun to embrace the long view, and begun to doubt the value of testing; they have begun to “opt-out”, which is now called the “opt-out parents movement” (Layton, 2013). The opt-out movement indicates a trend towards more play-based and learner-centered practices, advocated for by the American Psychological Association (APA) (Alexander & Murphy, 1998; Barbara, 2004; Cornelius-White, 2007; McCombs, 2001; McCombs & Miller, 2007; Weimer, 2013).

The benefits of play

Play is not only an imaginative activity of amusement. Play and games serve important roles in cognitive, social, and affective development (Dubbels, 2014; Fisher, 1992; Frost, 1998; Garvey, 1990). In pre-industrial times, pastoral and foraging societies, children did not learn sequestered away from adult contexts (Thomas, 1964). Instead, children participated in playful variations of adult activities, where they could observe adults at work, and were able to imitate and emulate these activities through play without the danger of failure and consequence (Bock, 2005; Rogoff, 1994).

Play is not only an imaginative activity of amusement. Play and games serve important roles in cognitive, social, and affective development (Dubbels, 2014; Fisher, 1992; Frost, 1998; Garvey, 1990). In pre-industrial times, pastoral and foraging societies, children did not learn sequestered away from adult contexts (Thomas, 1964). Instead, children participated in playful variations of adult activities, where they could observe adults at work, and were able to imitate and emulate these activities through play without the danger of failure and consequence (Bock, 2005; Rogoff, 1994).

Rubin, Fein, and Vandenberg provided a thorough psychological overview of the early role of play in their chapter in volume four of the Manual of Child Psychology (1983). They observed that humans play longer relative to other mammals that play. Lancaster and Lancaster (1987) built upon this position and state that this extended period of play is essential for development. Bjorklund, (2006) expands upon this view, and states that humans play longer because they are adaptive organisms, and, that extended play is essential, allowing humans the skills and knowledge to become independent in complex environments.

When children engage in complex peer play, they exhibit greater gains in levels of symbolic functional and oral language production, as compared to if they are interacting with an adult (Pellegrini, 1983). Additionally, when a learner experiences learning through play, where they can experience and role-play adult work, they report the activities are more meaningful, and that the activity did not feel like learning (Dubbels, 2010). This aligns with Winkielman & Cacioppo, (2001), who found that when learning new information is experienced as easy, processing is experienced as pleasant and effective.

Learning generated in the context of play, especially social play, can lead to greater engagement, improved recall, comprehension, and be more innovative. Juveniles can observe behaviors and strategies performed by adults but then recombine elements of these behaviors in novel routines in play (Bateson, 2005; Bruner, 1972; Fagen, 1981; Sutton-Smith, 1966). For example, the levels of children’s symbolic functional and oral language production are more varied and complex in peer play, relative to when they are interacting with an adult (Pellegrini, 1983). More importantly, play is a low-cost and low-risk way to learn new behaviors and acquire new skills and knowledge (ibid). Conversely, one could suggest that a limitation of direction instruction, observation, and imitating adults is that this kind of instruction will only transmit existing practices.

Offering activities to children in a playful mood can increase a willingness to take direction, and on-task behavior (Moore, Underwood, & Rosenhan, 1973; Rosenhan, Underwood, & Moore, 1974; Underwood, Froming, & Moore, 1977). To create a more playful mood, participants engage in playful communication, with emphasis on reducing or eliminating all commands, questions, and criticisms.

Play acts as an important organizing principle during developmental growth (Brown, 1998). Play is not only an imaginative activity; play also allows children to imitate and emulate adult work activities without the danger of failure. Children role-play activities from the adult world, and learn to use the tools, rules, and language of adult work. Play is an important part of academic learning. When children play, they develop new strategies and behaviors with minimal costs (Bateson, 2005; Burghardt, 2005; Spinka, Newbury, and Bekoff, 2001).

Using a playful approach in the classroom represents a fundamental change in assessment, offering a philosophy of playful and data-informed assessment, as compared to standardized, data-driven assessment. To be data-informed, assessments are used to guide the way, not to indicate that learning is accomplished. In play-based assessment, one can inform and improve student learning, increase motivation and engagement, and improve our school’s programs by learning from our challenges, progress, and performance.

Using a playful approach in the classroom represents a fundamental change in assessment, offering a philosophy of playful and data-informed assessment, as compared to standardized, data-driven assessment. To be data-informed, assessments are used to guide the way, not to indicate that learning is accomplished. In play-based assessment, one can inform and improve student learning, increase motivation and engagement, and improve our school’s programs by learning from our challenges, progress, and performance.

A playful structuring of assessment allows one to integrate play, and utilize assessment as a form of instructional communication, reducing threat, and emphasizing play. The value of such an approach is that it provides support for a range of students, including specialized support to educationally disadvantaged populations, including economically disadvantaged students, English Language Learners, students with disabilities, and students who are at risk of not meeting state academic standards.

References

Alexander, P. A., & Murphy, P. K. (1998). The research base for APA’s learner-centered psychological principles. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/books/10258/001

Anyon, J. (1980). Social class and the hidden curriculum of work. Sociology of Education: Major Themes, 162, 1250.

Atkinson, R. D., & Mayo, M. J. (2010). Refueling the US innovation economy: Fresh approaches to science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) education. The Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, Forthcoming. Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1722822

Banks, J., Carson, J. S., Nelson, B. L., & Nicol, D. M. (2001). Verification and validation of simulation models. Discrete-Event System Simulation, 3rd Edition, Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River (NJ), 367–397.

Barbara, L. (2004). The learner-centered psychological principles: A framework for balancing academic achievement and social-emotional learning outcomes. Building Academic Success on Social and Emotional Learning: What Does the Research Say?, 23.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(1), 5–31.

Brown, S. (1998). Play as an organizing principle: clinical evidence and personal observations. Animal Play: Evolutionary, Comparative, and Ecological Perspectives, 242–251.

Committee, R. A. the G. S. (2010). Rising above the gathering storm, revisited: Rapidly approaching Category 5. National Academies Press, Washington DC.

Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher-student relationships are effective: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 113–143.

Danielson, L. M. (2009). Fostering reflection. Educational Leadership, 66(5).

Dayen, D. (2015, April 3). The Biggest Outrage in Atlanta’s Crazy Teacher Cheating Case. Retrieved April 4, 2015, from http://finance.yahoo.com/news/biggest-outrage-atlanta-crazy-teacher-091500508.html

Deno, S. L., & Marston, D. (2006). Curriculum-based measurement of oral reading: An indicator of growth in fluency. What Research Has to Say about Fluency Instruction, 179–203.

Dubbels. (2014). Play: A Framework for Design, Development, & Gamification. Retrieved from http://www.yorku.ca/intent/issue7/articles/pdfs/brockrdubbelsarticle.pdf

Dubbels, B. (2008). Rhythm & Flow: Putting words to music as performance reading with garage band. In Professionalism in Practice (Vol. 1). The University of Minnesota: Minneapolis Public Schools.

Dubbels, B. (2010). Engineering curriculum and 21st century learning–improving academic performance with play and game design. In Games in Engineering & Computer Science GECS. National Science Foundation, Arlington, VA: NSF Course, Curriculum, and Laboratory Instruction program under Award No. 0938176. Retrieved from http://gecs.tamu.edu/index.php

Dubbels, B. (2013). Gamification, Serious Games, Ludic Simulation, and other Contentious Categories. International Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations (IJGCMS), 5(2).

Dweck, C. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House. Retrieved from http://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=fdjqz0TPL2wC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=Mindset:+The+New+Psychology+of+Success&ots=Bh76YKyGPD&sig=qkBjC2j6J9chNBClclBomJEANwI

Dweck, C. S. (2007). The perils and promises of praise. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=QDwqACGdf0IC&oi=fnd&pg=PA57&dq=dweck+growth+mindset+academic+&ots=9rif4lroXa&sig=eOdyOEMPi3kt7oFFQh-ctyXZ2bA

Easterbrook, J. A. (1959). The effect of emotion on cue utilization and the organization of behavior. Psychological Review, 66(3), 183.

Elliot, A. J., & Covington, M. V. (2001). Approach and avoidance motivation. Educational Psychology Review, 13(2), 73–92.

Elliot, A. J., Gable, S. L., & Mapes, R. R. (2006). Approach and avoidance motivation in the social domain. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(3), 378–391.

Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2012). Close reading in elementary schools. The Reading Teacher, 66(3), 179–188.

Fisher, E. P. (1992). The impact of play on development: A meta-analysis. Play & Culture, 5(2), 159–181.

Fisher, M. (2013, April 15). Map: How 35 countries compare on child poverty (the U.S. is ranked 34th). The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/worldviews/wp/2013/04/15/map-how-35-countries-compare-on-child-poverty-the-u-s-is-ranked-34th/

Forehand, R., & Scarboro, M. E. (1975). An analysis of children’s oppositional behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 3(1), 27–31.

Forgas, J. P., Burnham, D. K., & Trimboli, C. (1988). Mood, memory, and social judgments in children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(4), 697–703. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.4.697

Forster, M. (2009). Informative Assessment—understanding and guiding learning. Retrieved from http://research.acer.edu.au/research_conference/RC2009/17august/11/

Fox, E. (2008). Emotion Science. Retrieved from http://www.palgrave.com%2Fpage%2Fdetail%2Femotion-science-elaine-fox%2F%3FK%3D9780230005174

Frost, J. L. (1998). Neuroscience, Play, and Child Development. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED427845.pdf

Gabe, T. (2015). Poverty in the United States: 2013 (Congressional Research Service No. RL33069). Retrieved from https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL33069.pdf

Gable, P. A., & Poole, B. D. (2012). Time Flies When You’re Having Approach-Motivated Fun Effects of Motivational Intensity on Time Perception. Psychological Science, 23(8), 879–886.

Garvey, C. (1990). Play. Harvard Univ Pr. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=d711jR0AqvIC&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=garvey+play+1990&ots=YxJSWlZ7_K&sig=xCIVNP5RLJvPG2eGD_hU4esXoaM

Gavenda, V. (2005). GarageBand 2 for Mac OS X (Visual QuickStart Guide). Peachpit Press. Retrieved from http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1197774

Ginsburg, K. R. (2007). The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bonds. Pediatrics, 119(1), 182–191.

Gunnar, M., & Quevedo, K. (2007). The neurobiology of stress and development. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 58, 145–173.

Johnson, S. M., & Lobitz, G. K. (1974). The personal and marital adjustment of parents as related to observed child deviance and parenting behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 2(3), 193–207.

Kindergarten. (2015, December 10). In Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Kindergarten&oldid=694674848

Kohl, H. (1992). I won’t learn from you! Thoughts on the role of assent in learning. Rethinking Schools, 7(1), 16–17.

Kohl, H. (1994). I won’t learn from you. Confronting Student Resistance in Our Classrooms. Teaching for Equity and Social Justice, 134–135.

Lay, K.-L., Waters, E., & Park, K. A. (1989). Maternal Responsiveness and Child Compliance: The Role of Mood as a Mediator. Child Development, 60(6), 1405–1411. http://doi.org/10.2307/1130930

Layton, L. (2013). Bush, Obama focus on standardized testing leads to “opt-out” parents” movement. The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://216.78.200.159/RandD/Washington%20Post/Focus%20on%20Testing%20Leads%20to%20%E2%80%98Opt-Out%E2%80%99%20Movement%20-%20Post.pdf

Leistyna, P. (2007). Corporate testing: Standards, profits, and the demise of the public sphere. Teacher Education Quarterly, 59–84.

Lupien, S. J., McEwen, B. S., Gunnar, M. R., & Heim, C. (2009). Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 434–445.

McCombs, B. L. (2001). What do we know about learners and learning? The learner-centered framework: Bringing the educational system into balance. Educational Horizons, 182–193.

McCombs, B. L., & Miller, L. (2007). Learner-Centered Classroom Practices and Assessments: Maximizing Student Motivation, Learning, and Achievement. Corwin Press.

McNeil, L., & Valenzuela, A. (2000). The harmful impact of the TAAS system of testing in Texas: Beneath the accountability rhetoric. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED443872

Milteer, R. M., Ginsburg, K. R., Health, C. on C. and M. C. on P. A. of C. and F., & Mulligan, D. A. (2012). The Importance of Play in Promoting Healthy Child Development and Maintaining Strong Parent-Child Bond: Focus on Children in Poverty. Pediatrics, 129(1), e204–e213. http://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2953

Moore, B. S., Underwood, B., & Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). Affect and altruism. Developmental Psychology, 8(1), 99.

Papert, S. (1980). Mindstorms: Children, computers, and powerful ideas. Basic Books, Inc. Retrieved from http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1095592

Parpal, M., & Maccoby, E. E. (1985). Maternal responsiveness and subsequent child compliance. Child Development, 1326–1334.

Peed, S., Roberts, M., & Forehand, R. (1977). Evaluation of the Effectiveness of a Standardized Parent Training Program in Altering the Interaction of Mothers and their Noncompliant Children. Behavior Modification, 1(3), 323–350. http://doi.org/10.1177/014544557713003

Porter, A., McMaken, J., Hwang, J., & Yang, R. (2011). Common core standards the new US intended curriculum. Educational Researcher, 40(3), 103–116.

Ravitch, D. (2013, December 5). Daniel Wydo Disaggregates PISA Scores by Income. Retrieved from http://dianeravitch.net/2013/12/05/daniel-wydo-disaggregates-pisa-scores-by-income/

Recess (break). (2015, December 7). In Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Recess_(break)&oldid=694207866

Reddy, L. A., Files-Hall, T. M., & Schaefer, C. E. (2005). Announcing empirically based play interventions for children. Empirically Based Play Interventions for Children, 3–10.

Resnick, M., & Silverman, B. (2005). Some reflections on designing construction kits for kids. In Proceedings of the 2005 conference on Interaction design and children (pp. 117–122). ACM. Retrieved from http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1109556

Rosenhan, D. L., Underwood, B., & Moore, B. (1974). Affect moderates self-gratification and altruism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 30(4), 546.

Rumberger, R., & Palardy, G. (2005). Does segregation still matter? The impact of student composition on academic achievement in high school. The Teachers College Record, 107(9), 1999–2045.

Sackett, A. M., Meyvis, T., Nelson, L. D., Converse, B. A., & Sackett, A. L. (2010). You’re having fun when time flies the hedonic consequences of subjective time progression. Psychological Science, 21(1), 111–117.

Sahlberg, P. (2007). Education policies for raising student learning: The Finnish approach. Journal of Education Policy, 22(2), 147–171.

Shaffer, D. W. (2006). Epistemic frames for epistemic games. Computers & Education, 46(3), 223–234.

Shaffer, D. W. (2006). How computer games help children learn. Macmillan.

Sirin, S. R. (2005). Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 417–453.

Soderstrom, N. C., & Bjork, R. A. (2015). Learning Versus Performance An Integrative Review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 176–199.

Strauss, V. (2015, March 30). Report: Big education firms spend millions lobbying for pro-testing policies. The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/answer-sheet/wp/2015/03/30/report-big-education-firms-spend-millions-lobbying-for-pro-testing-policies/

Sutton-Smith, B. (2001). The ambiguity of play. Harvard Univ Pr. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=AgA8q0TCKeIC&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=sutton-smith&ots=Cna4A0r15X&sig=bjS1AtbvJP8cohAj52Oi2lZB1RE

Tennie, C., Call, J., & Tomasello, M. (2006). Push or pull: Imitation vs. emulation in great apes and human children. Ethology, 112(12), 1159–1169.

Underwood, B., Froming, W. J., & Moore, B. S. (1977). Mood, attention, and altruism: A search for mediating variables. Developmental Psychology, 13(5), 541.

(US Committee on Prospering in the Global Economy of the 21st Century, Science, & (US), P. P. (2007). Rising above the gathering storm: Energizing and employing America for a brighter economic future. National Academies Press. Retrieved from http://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=KoQf1m-s10UC&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=Rising+Above+the+Gathering+Storm,+Energizing+and+Employing+America+for+a+Brighter+Economic+Future&ots=8otcXacPcm&sig=DepAfNSa-sXWLGNOD0F9nFlVZtQ

Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice (2 edition). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

White, K. R. (1982). The relation between socioeconomic status and academic achievement. Psychological Bulletin, 91(3), 461.

Whiten, A., McGuigan, N., Marshall-Pescini, S., & Hopper, L. M. (2009). Emulation, imitation, over-imitation and the scope of culture for child and chimpanzee. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1528), 2417–2428.

Wiliam, D. (2007). Changing classroom practice. Educational Leadership, 65(4), 36.

Wiliam, D., & Thompson, M. (2007). Integrating assessment with learning: what will it take to make it work? Retrieved from http://eprints.ioe.ac.uk/1162/

Winkielman, P., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2001). Mind at ease puts a smile on the face: psychophysiological evidence that processing facilitation elicits positive affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(6), 989.

Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47(4), 302–314.

CHA P T E R 4

CHA P T E R 4

Pedagogy and Play: Creating a Playful Curriculum for

Academic Achievement and Engaged Learning

Brock R. Dubbels, PhD., Dept. Psychology, Neuroscience, & Behavior, McMaster University, Hamilton,

ON, Canada, Dubbels@McMaster.ca

Key Summary Points

Using instructional techniques based upon play can improve achievement. Standardization has created more problems than it solved. Three case studies are presented as demonstrations of the framework. When children engage in complex peer play, they exhibit greater gains in levels of symbolic functional and oral language production.

Key Terms

Play, Assessment, Learner Centered Practices, Instructional Communication, Curriculum, Cognitive, Affect, Classroom, Instructional Design, Learning

The Benefits of Play

Play is not only an imaginative activity of amusement. Play and games serve important roles in cognitive, social, and affective development (Dubbels, 2014; Fisher, 1992; Frost, 1998; Garvey, 1990). In pre-industrial times, pastoral and foraging societies, children did not learn sequestered away from adult contexts (Thomas, 1964). Instead, children participated in playful variations of adult activities, where they could observe adults at work, and were able to imitate and emulate these activities through play without the danger of failure and consequence (Bock, 2005; Rogoff, 1994). Rubin, Fein, and Vandenberg provided a thorough psychological overview of the early role of play in their chapter in volume four of the Manual of Child Psychology (1983). They observed that humans play longer relative to other mammals that play. Lancaster and Lancaster (1987) built upon this position and state that this extended period of play is essential for development. Bjorklund, (2006) expands upon this view, and states that humans play longer because they are adaptive organisms, and, that extended play is essential, allowing humans the skills and knowledge to become independent in complex environments. When children engage in complex peer play, they exhibit greater gains in levels of symbolic functional and oral language production, as compared to if they are interacting with an adult (Pellegrini, 1983). Additionally, when a learner experiences learning through play, where they can experience and roleplay adult work, they report the activities are more meaningful, and that the activity did not feel like learning (Dubbels, 2010). This aligns with Winkielman & Cacioppo, (2001), who found that when learning new information is experienced as easy, processing is experienced as pleasant and effective.

Read more of this article, download, feel good

CFP: eSports and professional game play

The purpose of this special issue is to investigate the rise of eSports.

Much has happened in the area of professional gaming since the Space Invaders Championship of 1980. We have seen live Internet streaming eclipse televised eSports events, such as on the American show Starcade.

Authors are invited to submit manuscripts that

- Examine the emergence of eSports

- The uses of streaming technology

- Traditions of games that support professional players – chess, go, bridge, poker, league of legends, Dota 2, Starcraft

- Fan perspectives

- Professional player perspectives

- Market analysis

- Meta-analyses of existing research on eSports

- Answer specific questions such as:

- How should game user research examine the emergence of eSports? Should we differentiate pragmatic and hedonic aspects of the game?

- What are the methodologies for conducting research on eSports?

- What is the role of player, the audience, the developer, the venue?

- Case studies, worked examples, empirical and phenomenological, application of psychological and humanist approaches?

- Field research

- Face to face interviewing

- Creation of user tests

- Gathering and organizing statistics

- Define Audience

- User scenarios

- Creating Personas

- Product design

- Feature writing

- Requirement writing

- Content surveys

- Graphic Arts

- Interaction design

- Information architecture

- Process flows

- Usability

- Prototype development

- Interface layout and design

- Wire frames

- Visual design

- Taxonomy and terminology creation

- Copywriting

- Working with programmers and SMEs

- Brainstorm and managing scope (requirement) creep

- Design and UX culture

Potential authors are encouraged to contact Brock R. Dubbels (Dubbels@mcmaster.ca) to ask about the appropriateness of their topic.

Deadline for Submission July 2016.

Authors should submit their manuscripts to the submission system using the following link:

http://www.igi-global.com/authorseditors/titlesubmission/newproject.aspx

(Please note authors will need to create a member profile in order to upload a manuscript.)

Manuscripts should be submitted in APA format.

They will typically be 5000-8000 words in length.

Full submission guidelines can be found at: http://www.igi-global.com/journals/guidelines-for-submission.aspx

Mission – IJGCMS is a peer-reviewed, international journal devoted to the theoretical and empirical understanding of electronic games and computer-mediated simulations. IJGCMS publishes research articles, theoretical critiques, and book reviews related to the development and evaluation of games and computer-mediated simulations. One main goal of this peer-reviewed, international journal is to promote a deep conceptual and empirical understanding of the roles of electronic games and computer-mediated simulations across multiple disciplines. A second goal is to help build a significant bridge between research and practice on electronic gaming and simulations, supporting the work of researchers, practitioners, and policymakers.

The eHealth Seminar Series welcomes

Brock Dubbels, PhD

Department of Computing and Software, McMaster University

Abstract:

Do games and play have a place as medical interventions? How can games and play inform designing instruction and assessment contexts? Can games and similar software design per- suade individuals towards healthier lifestyles and adherence? In this overview, research will be presented from studies and experimentation from laboratory and instructional settings as evidence for using games for accelerating learning outcomes, persuasion, medical inter- ventions, as well as professional development and productivity. Games offer individuals a learning environment rich with choice and feedback . . . not only for gathering information about learning, but scaffolding learners towards competence and mastery in recall, comprehension, and problem solving. The difficulty with games may be our view that games are a form of play, an undirected, frivolous children’s activity. In this presentation research and examples of games and play inspired activities will be presented for motivating learners, designing effective instruction, improving comprehension and problem solving, providing therapeutic interventions, aid- ing in work-place productivity, and professional development.

Brock Dubbels Ph.D.is an experimental psychologist at the G-Scale Game development and testing laboratory at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. His appointment includes work in the Dept. of Computing and Software (G-Scale) and the McMaster Research Libraries. Brock specializes in games and software for knowledge and skill acquisition, eHealth, and clinical interventions.

Brock Dubbels has worked since 1999 as a professional in education and instructional design. His specialties include com- prehension, problem solving, and game design. From these perspectives he designs face-to-face, virtual, and hybrid learn- ing environments, exploring new technologies for assessment, delivering content, creating engagement with learners, and investigating ways people approach learning. He has worked as a Fulbright Scholar at the Norwegian Institute of Science and Technology; at Xerox PARC and Oracle, and as a research associate at the Center for Cognitive Science at the Universi- ty of Minnesota. He teaches course work on games and cognition, and how learning research can improve game design for return on investment (ROI). He is also the founder and principal learning architect at www.vgalt.com for design, production, usability assessment and evaluation of learning systems and games.

And rumour has it, he has a sweet bike!

I want to invite you to a colloquium March 7, at 1430– Department of Psychology, Neuroscience & Behaviour (PNB)

at McMaster University

Video Games as Learning Tools

Brock Dubbels, PhD.,

G-ScalE Game Development and Testing Lab

McMaster University

Dubbels@McMaster.ca

Should games and play be considered important in designing instructional contexts? Should they be used for professional development, or even become a part of our productivity at work? Games offer individuals a learning environment rich with choice and feedback . . . not only for gathering information about a student’s learning, but that also demand mastery in recall, comprehension, and problem solving. The difficulty with games may be our view that games are a form of play, an undirected, frivolous children’s activity . In this presentation research and examples of games and play inspired activities will be presented for motivating learners, designing effective instruction, improving comprehension and problem solving, providing therapeutic interventions, aiding in work-place productivity, and professional development.

Department of Psychology, Neuroscience & Behaviour (PNB)

Psychology Building (PC), Room 102

McMaster University

1280 Main Street West

http://www.science.mcmaster.ca/pnb/news-events/colloquium-series-events/details/274-brock-dubbels-tba.html

What we cannot know or do individually, we may be capable of collectively.

My research examines the transformation of perceptual knowledge into conceptual knowledge. Conceptual knowledge can be viewed as crystallized, which means that it has become abstracted and is often symbolized in ways that do not make the associated meaning obvious. Crystallized knowledge is the outcome of fluid intelligence, or the ability to think logically and solve problems in novel situations, independent of acquired knowledge. I investigate how groups and objects may assist in crystallization of knowledge, or the construction of conceptual understanding.

I am currently approaching this problem from the perspective that cognition is externalized and extended through objects and relationships. Â This view posits that skill, competence, knowledge are learned through interaction aided with objects imbued with collective knowledge.

Groups make specialized information available through objects and relationships so that individual members can coordinate their actions and do things that would be hard or impossible for them to enact individually. To examine this, I use a socio-cognitive approach, which views cognition as distributed, where information processing is imbued in objects and communities and aids learners in problem solving.

This socio-cognitive approach is commonly associated with cognitive ethnography and the study of social networks. In particular, I have special interest in how play, games, modeling, and simulations can be used to enhance comprehension and problem solving through providing interactive learning. In my initial observational studies, I have found that games are structured forms of play, which work on a continuum of complexity:

- Pretense, imagery and visualization of micro worlds

- Tools, rules, and roles

- Branching / probability

Games hold communal knowledge, which can be learned through game play. An example of this comes from the board game Ticket to Ride. In this strategy game players take on the role of a railroad tycoon in the early 1900′s. The goal is to build an empire that spans the United States while making shrewd moves that block your opponents from being able to complete their freight and passenger runs to various cities. Game play scaffolds the learner in the history and implications of early transportation through taking on the role of an entrepreneur and learning the context and process of building up a railroad empire. In the course of the game, concept are introduced, with language, and value systems based upon the problem space created by the game mechanics (artifacts, scoring, rules, and language). The game can be analyzed as a cultural artifact containing historical information; a vehicle for content delivery as a curriculum tool; as well as an intervention for studying player knowledge and decision-making.

I have observed that learners interact with games with growing complexity of the game as a system. As the player gains top sight, a view of the whole system, they play with greater awareness of the economy of resources, and in some cases an aesthetic of play. For beginning players, I have observed the following progression:

- Trial and error – forming a mental representation, or situation model of how the roles, rules, tools, and contexts work for problem solving.

- Tactical trials – a successful tactic is generated to solve problems using the tools, rules, roles, and contexts. This tactic may be modified for use in a variety of ways as goals and context change in the game play.

- Strategies—the range of tactics of resulted in strategies that come from a theory of how the game works. This approach to problem solving indicates a growing awareness of systems knowledge, the purpose or criteria for winning, and is a step towards top sight. They understand that there are decision branches, and each decision branch comes with risk reward they can evaluate in the context of economizing resources.

- Layered strategies—the player is now making choices based upon managing resources because they are now economizing resources and playing for optimal success with a well-developed mental representation of the games criteria for winning, and how to have a high score rather than just finish.

- Aesthetic of play—the player understands the system and has learned to use and exploit ambiguities in the rules and environment to play with an aesthetic that sets the player apart from others. The game play is characterized with surprising solutions to the problem space.

For me, games are a structured form of play. As an example, a game may playfully represent an action with associated knowledge, such as becoming a railroad tycoon, driving a high performance racecar, or even raising a family. Games always involve contingent decision-making, forcing the players to learn and interact with cultural knowledge simulated in the game.

Games currently take a significant investment of time and effort to collectively construct. These objects follow in a history of collective construction by groups and communities. Consider the cartography and the creation of a map as an example of collective distributed knowledge imbued in an object. Â According to Hutchins (1996),

“A navigation chart represents the accumulation of more observations than any one person could make in a lifetime. It is an artifact that embodies generations of experience and measurement. No navigator has ever had,nor will one ever have, all the knowledge that is in the chart.â€

A single individual can use a map to navigate an area with competence, if not expertise. Observing an individual learning to use a map, or even construct one is instructive for learning about comprehension and decision-making. Interestingly, games provide structure to play, just as maps and media appliances provide structure to data to create information. Objects such as maps and games are examples of collective knowledge, and are what Vygotsky termed a pivot.

The term pivot was initially conceptualized in describing children’s play, particularly as a toy. A toy is a representation used in aiding knowledge construction in early childhood development. This is the transition where children may move from recognitive play to symbolic and imaginative play, i.e. the child may play with a phone the way it is supposed to be used to show they can use it (recognitive), and in symbolic or imaginative play, they may pretend a banana is the phone.

This is an important step since representation and abstraction are essential in learning language, especially print and alphabetical systems for reading and other discourse. In this sense, play provides a transitional stage in this direction whenever an object (for example a stick) becomes a pivot for severing meaning of horse from a real horse. The child cannot yet detach thought from object. (Vygotsky, 1976, p 97). For Vygotsky, play represented a transition in comprehension and problem solving –where the child moved from external processing — imagination in action —to internal processing — imagination as play without action.

In my own work, I have studied the play of school children and adults as learning activities. This research has informed my work in classroom instruction and game design. Learning activities can be structured as a game, extending the opportunity to learn content, and extend the context of the game into other aspects of the learner’s life, providing performance data and allowing for self-improvement with feedback, and data collection that is assessed, measured and evaluated for policy.

My research and publications have been informed by my work as a tenured teacher and software developer. A key feature of my work is the importance of designing for learning transfer and construct validity. When I design a learning environment, I do so with research in mind. Action research allows for reflection and analysis of what I created, what the learners experienced, and an opportunity to build theory. What is unique about what I do is the systems approach and the way I reverse engineer play as a deep and effective learning tool into transformative learning, where pleasurable activities can be counted as learning.

Although I have published using a wide variety of methodologies, cognitive ethnography is a methodology typically associated with distributed cognition, and examines how communities contain varying levels of competence and expertise, and how they may imbue that knowledge in objects. I have used it specifically on game and play analysis (Dubbels 2008, 2011). This involves observation and analysis of Space or Context—specifically conceptual space, physical space, and social space. The cognitive ethnographer transforms observational data and interpretation of space into meaningful representations so that cognitive properties of the system become visible (Hutchins, 2010; 1995). Cognitive ethnography seeks to understand cognitive process and context—examining them together, thus, eliminating the false dichotomy between psychology and anthropology. This can be very effective for building theories of learning while being accessible to educators.

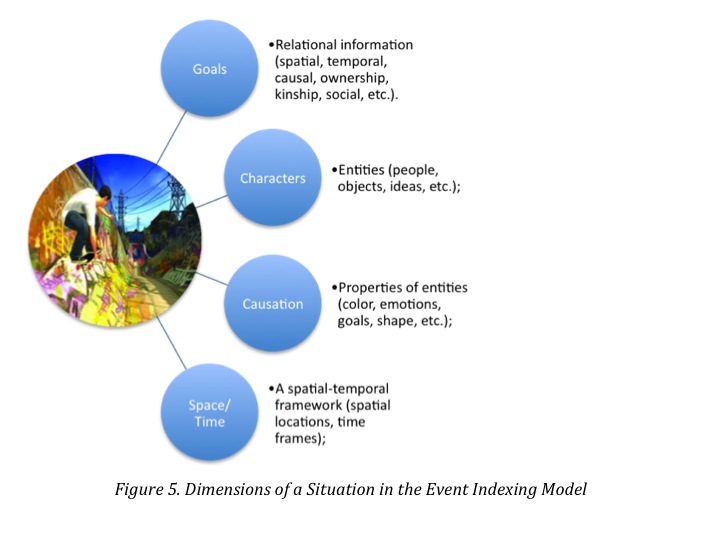

My current interest is in the use of cognitive ethnographic methodology with traditional form serves as an opportunity to move between inductive and deductive inquiry and observation to build a Nomological network (Cronbach & Meehl, 1955) using measures and quantified observations with the Multiple Trait and Multiple Method Matrix Analysis (Campbell & Fiske, 1959) for construct validity (Cook & Campbell, 1979; Campbell & Stanley, 1966) especially in relation to comprehension and problem solving based upon the Event Indexing Model (Zwaan & Radvansky, 1998).

We distribute knowledge because it is impossible for a single human being, or even a group to have mastery of all knowledge and all skills (Levy, 1997). For this reason I study access and quality of collective group relations and objects and the resulting comprehension and problem solving. The use of these objects and relations can scaffold learners and inform our understanding of how perceptual knowledge is internalized and transformed into conceptual knowledge through learning and experience.

Specialties

Educational research in cognitive psychology, social learning. identity, curriculum and instruction, game design, theories of play and learning, assessment, instructional design, and technology innovation.

Additionally:

The convergence of media technologies now allow for collection, display, creation, and broadcast of information as narrative, image, and data. This convergence of function makes two ideas important in the study of learning:

- The ability to create of media communication through narrative, image, and data analysis and information graphics is becoming more accessible to non-experts through media appliances such as phones, tablets, game consoles and personal computers.

- These media appliances have taken very complex behaviors such as film production, which in the past required teams of people with special skill and knowledge, and have imbued these skills and knowledge in hand-held devices that are easy to use, and are available to the general population.

- This accessibility allows novices to learn complex media production, analysis, and broadcast, and allows for the study of these devices as object that has been imbued with the knowledge and skill, as externalized cognitionThrough the use of these devices, the general population may learn complex skills and knowledge that may have required years of specialized training in the past. Study of the interaction between of individuals learning to use these appliances and devices can be studied as a progression of internalizing knowledge and skill imbued in objects.

- The convergence of media technologies into small, single–even handheld—devices emphasizes that technology for producing media may change, but the narrative has remained relatively consistent.

- This consistency of media as narrative, imagery, and data analysis emphasizes the importance of the continued study of narrative comprehension and problem solving through the use of these media appliances.

I don’t think anyone would disagree — fostering creativity should be a goal of classroom learning.

However, the terms creativity and innovation are often misused. When used they typically imply that REAL learning cannot be measured. Fortunately, we know A LOT about learning and how it happens now. It is measurable and we can design learning environments that promote it. It is the same with creativity as with intelligence–we can promote growth in creativity and intelligence through creative approaches to pedagogy and assessment. Because data-driven instruction does not kill creativity, it should promote it.

One of the ways we might look at creativity and innovation is through the much maligned tradition of intelligence testing as described in the Wikipedia:

Fluid intelligence or fluid reasoning is the capacity to think logically and solve problems in novel situations, independent of acquired knowledge. It is the ability to analyze novel problems, identify patterns and relationships that underpin these problems and the extrapolation of these using logic. It is necessary for all logical problem solving, especially scientific, mathematical and technical problem solving. Fluid reasoning includes inductive reasoning and deductive reasoning, and is predictive of creativity and innovation.

Crystallized intelligence is indicated by a person’s depth and breadth of general knowledge, vocabulary, and the ability to reason using words and numbers. It is the product of educational and cultural experience in interaction with fluid intelligence and also predicts creativity and innovation.

The Myth of Opposites

Creativity and intelligence are not opposites. It takes both for innovation.

What we often lack are creative ways of measuring learning growth in assessments. When we choose to measure growth in summative evaluations and worksheets over and over , we nurture boredom and kill creativity.

To foster creativity, we need to adopt and implement pedagogy and curriculum that promotes creative problems solving, and also provides criteria that can measure creative problem solving.

What is needed are ways to help students learn content in creative ways through the use of creative assessments.

We often confuse the idea of  learning creatively with trial and error and play, free of any kind of assessment–that somehow the Mona Lisa was created through just free play and doodling. That somehow assessment kills creativity.  Assessment provide learning goals.

Without learning criteria, students are left to make sense of the problem put before them with questions like “what do I do now?” (ad infinitum).

The role of the educator is to design problems so that the solution becomes transparent. This is done through providing information about process, outcome, and quality criteria . . . assessment, is how it is to be judged. For example, “for your next assignment, I want a boat that is beautiful and  that is really fast. Here are some examples of boats that are really fast.  Look at the hull, the materials they are made with, etc. and design me a boat that goes very fast and tell me why it goes fast. Tell me why it is beautiful.” Now use the terms from the criteria. What is beautiful? Are you going to define it? How about fast? Fast compared to what? These open-ended, interest-driven, free play assignments might be motivating, but they lead to quick frustration and lots of “what do I do now?”

But play and self-interest arte not the problem here. The problem is the way we are approaching assessment.

Although play is described as a range of voluntary, intrinsically motivated activities normally associated with recreational pleasure and enjoyment; Pleasure and enjoyment still come from judgements about one’s work–just like assessment–whether finger painting or creating a differential equation. The key feature here is that play seems to involve self-evaluation and discovery of key concepts and patterns. Assessments can be constructed to scaffold and extend this, and this same process can be structured in classrooms through assessment criteria.

Every kind of creative play activity has evaluation and self-judgement: the individual is making judgements about pleasure, and often why it is pleasurable. This is often because they want to replicate this pleasure in the future, and oddly enough, learning is pleasurable. So when we teach a pleasurable activity, the learning may be pleasurable. This means chunking the learning and concepts into larger meaning units such as complex terms and concepts, which represent ideas, patterns, objects, and qualities. Thus, crystallized intelligence can be constructed through play as long as the play experience is linked and connected to help the learner to define and comprehend the terms (assessment criteria). So when the learner talks about their boat, perhaps they should be asked to sketch it first, and then use specific terms to explain their design:

Bow is the frontmost part of the hull

Stern is the rear-most part of the hull

Port is the left side of the boat when facing the Bow

Starboard is the right side of the boat when facing the Bow

Waterline is an imaginary line circumscribing the hull that matches the surface of the water when the hull is not moving.

Midships is the midpoint of the LWL (see below). It is half-way from the forwardmost point on the waterline to the rear-most point on the waterline.

Baseline an imaginary reference line used to measure vertical distances from. It is usually located at the bottom of the hull

Along with the learning activity and targeted learning criteria and content, the student should be asked a guiding question to help structure their description.

So, how do these parts affect the performance of the whole?

Additionally, the learner should be adopting the language (criteria) from the rubric to build comprehension. Taking perception, experience, similarities and contrasts to understand Bow and Stern, or even Beauty.

Experiential Learning for Fluidity and Crystallization

What the tradition of intelligence offers is an insight as to how an educator might support students. What we know is that intelligence is not innate. It can change through learning opportunities. The goal of the teacher should be to provide experiential learning that extends Fluid Intelligence, through developing problem solving, and link this process to crystallized concepts in vocabulary terms that encapsulate complex process, ideas, and description.

The real technology in a 21st Century Classroom is in the presentation and collection of information. It is the art of designing assessment for data-driven decision making. The role of the teacher should be in grounding crystallized academic concepts in experiential learning with assessments the provide structure for creative problem solving. The teacher creates assessments where the learning is the assessment. The learner is scaffolded through the activity with guidance of assessment criteria.

A rubric, which provides criteria for quality and excellence can scaffold creativity innovation, and content learning simultaneously. A well-conceived assessment guides students to understand descriptions of quality and help students to understand crystallized concepts.

An example of a criteria-driven assessment looks like this:

| Purpose & Plan | Isometric Sketch | Vocabulary | Explanation | |

| Level up | Has identified event and hull design with reasoning for appropriateness. | Has drawn a sketch where length, width, and height are represented by lines 120 degrees apart, with all measurements in the same scale. | Understanding is clear from the use of five key terms from the word wall to describe how and why the boat hull design will be successful for the chosen event. | Clear connection between the hull design, event, sketch, and important terms from word wall and next steps for building a prototype and testing. |

| Approaching | Has chosen a hull that is appropriate for event but cannot connect the two. | Has drawn Has drawn a sketch where length, width, and height are represented. | Uses five key terms but struggles to demonstrate understanding of the terms in usage. | Describes design elements, but cannot make the connection of how they work together. |

| Do it again | Has chosen a hull design but it may not be appropriate for the event. | Has drawn a sketch but it does not have length, width, and height represented. | Does not use five terms from word wall. | Struggles to make a clear connection between design conceptual design stage elements. |

What is important about this rubric is that it guides the learner in understanding quality and assessment. It also familiarizes the learner with key crystallized concepts as part of the assessment descriptions. In order to be successful in this playful, experiential activity (boat building),  the learner must learn to comprehend and demonstrate knowledge of the vocabulary scattered throughout the rubric such as: isometric, reasoning, etc. This connection to complex terminology grounded with experience is what builds knowledge and competence. When an educator can coach a student connecting their experiential learning with the assessment criteria, they construct crystallized intelligence through grounding the concept in experiential learning, and potentially expand fluid intelligence through awareness of new patterns in form and structure.

Play is Learning, Learning is Measurable

Just because someone plays, or explores does not mean this learning is immeasurable. The truth is, research on creative breakthroughs demonstrate that authors of great innovation learned through years of dedicated practice and were often judged, assessed, and evaluated.  This feedback from their teachers led them to new understanding and new heights. Great innovators often developed crystallized concepts that resulted from experience in developing fluid intelligence. This can come from copying the genius of others by replicating their breakthroughs; it comes from repetition and making basic skills automatic, so that they could explore the larger patterns resulting from their actions. It was the result of repetition and exploration, where they could reason, experiment, and experience without thinking about the mechanics of their actions.  This meant learning the content and skills from the knowledge domain and developing some level of automaticity. What sets an innovator apart it seems, is tenacity and being playful in their work, and working hard at their play.

According to Thomas Edison:

During all those years of experimentation and research, I never once made a discovery. All my work was deductive, and the results I achieved were those of invention, pure and simple. I would construct a theory and work on its lines until I found it was untenable. Then it would be discarded at once and another theory evolved. This was the only possible way for me to work out the problem. … I speak without exaggeration when I say that I have constructed 3,000 different theories in connection with the electric light, each one of them reasonable and apparently likely to be true. Yet only in two cases did my experiments prove the truth of my theory. My chief difficulty was in constructing the carbon filament. . . . Every quarter of the globe was ransacked by my agents, and all sorts of the queerest materials used, until finally the shred of bamboo, now utilized by us, was settled upon.

On his years of research in developing the electric light bulb, as quoted in “Talks with Edison” by George Parsons Lathrop in Harpers magazine, Vol. 80 (February 1890), p. 425

So when we encourage kids to be creative, we must also understand the importance of all the content and practice necessary to creatively breakthrough. Edison was taught how to be methodical, critical, and observant. He understood the known patterns and made variations. It is important to know the known forms to know the importance of breaking forms. This may inv0lve copying someone else’s design or ideas. Thomas Edison also speaks to this when he said:

Everyone steals in commerce and industry. I have stolen a lot myself. But at least I know how to steal.

Edison stole ideas from others, (just as Watson and Crick were accused of doing). The point Watson seems to be making here is that he knew how to steal, meaning, he saw how the parts fit together. He may have taken ideas from a variety of places, but he had the knowledge, skill, and vision to put them together. This synthesis of ideas took awareness of the problem, the outcome, and how things might work. Lots and lots of experience and practice.

To attain this level of knowledge and experience, perhaps stealing ideas, or copying and imitation are not a bad idea for classroom learning? However copying someone else in school is viewed as cheating rather than a starting point. Perhaps instead, we can take the criteria of examples and design classroom problems in ways that allow discovery and the replication of prior findings (the basis of scientific laws). It is often said that imitation is the greatest form of flattery. Imitation is also one of the ways we learn. In the tradition of play research, mimesis is imitation–Aristotle held that it was “simulated representation”.

The Role of Play and Games

In close, my hope is that we not use the terms “creativity” and “innovation” as suitcase words to diminish such things as minimum standards. We need minimum standards.

But when we talk about teaching for creativity and innovation, where we need to start is the way that we gather data for assessment. Often assessments are unimaginative in themselves. They are applied in ways that distract from learning, because they have become the learning. One of the worst outcomes of this practice is that students believe that they are knowledgeable after passing a minimum standards test. This is the soft-bigotry of low expectation. Assessment should be adaptive, criteria driven, and modeled as a continuous improvement cycle.

This does not mean that we must  drill and kill kids in grinding mindless repetition. Kids will grind towards a larger goal where they are offered feedback on their progress. They do it in games.

Games are structured forms of play. They are criteria driven, and by their very nature, games assess, measure, and evaluate. But they are only as good as their assessment criteria.

These concepts should be embedded in creative active inquiry that will allow the student to embody their learning and memory. However, many of the creative, inquiry-based lessons I have observed tend to ignore the focus of academic language–the crystallized concepts. Such as, “what is fast?”, “what is beauty”, Â “what is balance?”, or “what is conflict?” The focus seems to be on interacting with content rather than building and chunking the concepts with experience. When Plato describes the world of forms, and wants us to understand the essence of the chair, i.e., “what is chairness?” We may have to look at a lot of chairs to understand chairness. Â Bu this is how we build conceptual knowledge, and should be considered when constructing curriculum and assessment. A guiding curricular question should be:

How does the experience inform the concepts in the lesson?

There is a way to use data-driven instruction in very creative lessons, just like the very unimaginative drill and kill approach. Teachers and assessment coordinators need to take the leap and learn to use data collection in creative ways in constructive assignments that promote experiential learning with crystallized academic concepts.

If you have kids make a diorama of a story, have them use the concepts that are part of the standards and testing: Plot, Character, Theme, Setting, ETC. Make them demonstrate and explain. If you want kids to learn the physics have them make a boat and connect the terms through discovery. Use their inductive learning and guide them to conceptual understanding.This can be done through the use of informative assessments, such as with rubrics and scales for assessment.  Evaluation and creativity are not contradictory or mutually exclusive. These seeming opposites are complementary, and can be achieved through embedding the crystallized, higher order concepts into meaningful work.

This monograph describes cognitive ethnography as a method of choice for game studies, multimedia learning, professional development, leisure studies, and activities where context is important. Cognitive ethnography is efficacious for these activities as it  assumes that human cognition adapts to its natural surroundings (Hutchins, 2010; 1995) with emphasis on analysis of activities as they happen in context; how they are represented; and how they are distributed and experienced in space. Along with this, the methodology is described for increasing construct validity (Cook and Campbell, 1979; Campbell & Stanley, 1966) and the creation of a nomological network Cronbach & Meehl (1955). This description of the methodology is contextualized with a study examining the literate practices of reluctant middle school readers playing video games (Dubbels, 2008). The study utilizes variables from empirical laboratory research on discourse processing (Zwann, Langston, & Graesser, 1996) to analyze the narrative discourse of a video game as a socio-cognitive practice (Gee, 2007; Gee, Hull, & Lankshear, 1996).

This monograph describes cognitive ethnography as a method of choice for game studies, multimedia learning, professional development, leisure studies, and activities where context is important. Cognitive ethnography is efficacious for these activities as it  assumes that human cognition adapts to its natural surroundings (Hutchins, 2010; 1995) with emphasis on analysis of activities as they happen in context; how they are represented; and how they are distributed and experienced in space. Along with this, the methodology is described for increasing construct validity (Cook and Campbell, 1979; Campbell & Stanley, 1966) and the creation of a nomological network Cronbach & Meehl (1955). This description of the methodology is contextualized with a study examining the literate practices of reluctant middle school readers playing video games (Dubbels, 2008). The study utilizes variables from empirical laboratory research on discourse processing (Zwann, Langston, & Graesser, 1996) to analyze the narrative discourse of a video game as a socio-cognitive practice (Gee, 2007; Gee, Hull, & Lankshear, 1996).

Keywords:

Cognitive Ethnography, Methodology, Design, Game Studies, Validity, Comprehension, Discourse Processing, Reading, Literacy, Socio-Cognitive.

INTRODUCTION

As a methodological approach, cognitive ethnography assumes that cognition is distributed through rules, roles, language, relationships and coordinated activities, and can be embodied in artifacts and objects (Dubbels, 2008). For this reason, cognitive ethnography is an effective way to study activity systems like games, models, and simulations –whether mediated digitally or not.

BACKGROUND

In its traditional form, ethnography often involves the researcher living in the community of study, learning the language, doing what members of the community do—learning to see the world as it is seen by the natives in their cultural context, Fetterman (1998).

Cognitive ethnography follows the same protocol, but its purpose is to understand cognitive process and context—examining them together, thus, eliminating the false dichotomy between psychology and anthropology.

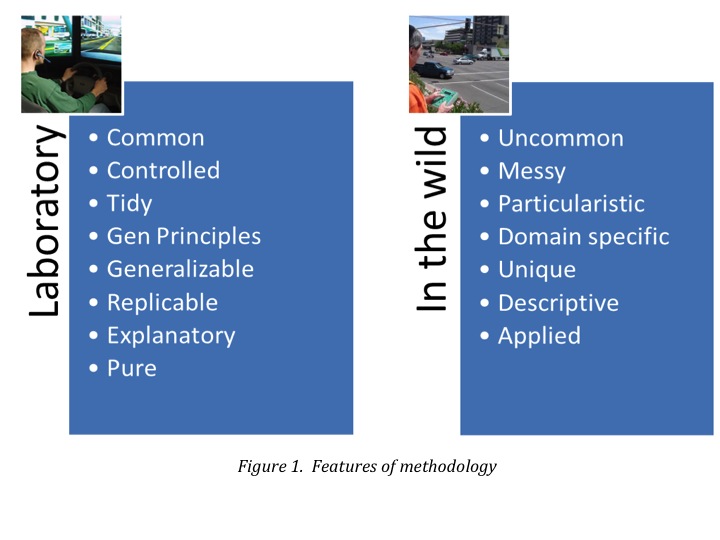

Observational techniques such as ethnography and cognitive ethnography attempt to describe and look at relations and interaction situated in the spaces where they are native. There are a number of advantages to both laboratory observation and in the wild as presented in Figure 1.

NOMOLOGICAL NETWORK

As mentioned, Cognitive Ethnography can be used as an attempt to provide evidence of construct validity. This approach, developed by Cronbach & Meehl (1955), posits that a researcher should provide a theoretical framework for what is being measured, an empirical framework for how it is to be measured, and specification of the linkage between these two frameworks. The idea is to link the conceptual/theoretical with the observable and examine the extent to which a construct, such as comprehension, behaves as it was expected to within a set of related constructs. One should attempt to demonstrate convergent validity by showing that measures that are theoretically supposed to be highly interrelated are, in practice, highly interrelated, and, that measures that shouldn’t be related to each other in fact are not.

This approach, the Nomological network is intended to increase construct validity, and external validity, as will be used in the example, the generalization from one study context, such as the laboratory, to another context, i.e., people, places, times. When we claim construct validity, we are essentially claiming that our observed pattern — how things operate in reality — corresponds with our theoretical pattern — how we think the world works. To do this, it is important to move outside of laboratory settings to observe the complex ways in which individuals and groups adapt to naturally occurring, culturally constituted activities.  By extending theory building with different approaches to research questions, and move from contexts observed in the wild, then refined in the laboratory, and then used as a lens in field observation.

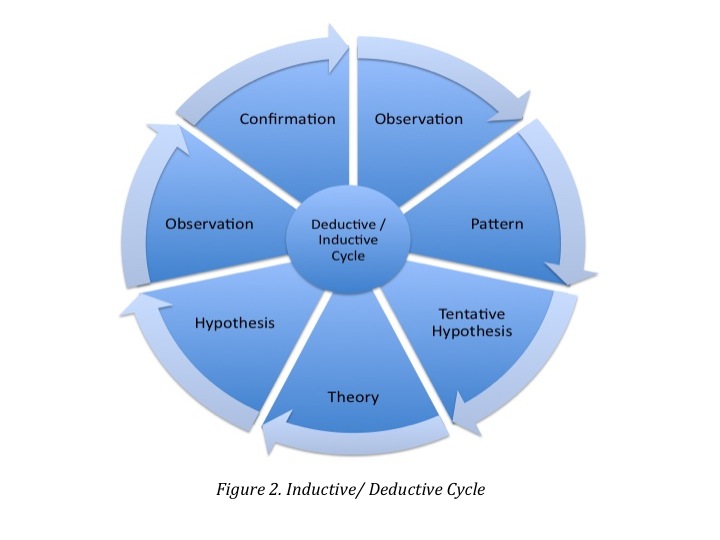

The pattern fits deductive/ inductive framework:

- Deductive: theory, hypothesis, observation, and confirmation

- Inductive: observation, pattern, tentative hypothesis,

These two approaches to research have a different purpose and approach. Most social research involves both inductive and deductive reasoning processes at some time in the project. It may be more reasonable to look at deductive/inductive approaches as a mixed, circular approach. Since cognition can be seen as embodied in cultural artifacts and behavior, cognitive ethnography is an apt methodology for the study of learning with games, in virtual worlds, and the study of activity systems, whether they are mediated digitally or not. By using the deductive/inductive approach, and expanding observation, one can contrast and challenge theoretical arguments by testing in expanded context.

Cognitive ethnography emphasizes inductive field observation, but also uses theory in a deductive process to analyze behavior. This approach is useful to increase external validity, operationalize terms, and develop content validity through expanding a study across new designs, across different time frames, in different programs, from different observational contexts, and with different groups (Cook and Campbell, 1979; Campbell & Stanley, 1966).

Cognitive ethnography emphasizes inductive field observation, but also uses theory in a deductive process to analyze behavior. This approach is useful to increase external validity, operationalize terms, and develop content validity through expanding a study across new designs, across different time frames, in different programs, from different observational contexts, and with different groups (Cook and Campbell, 1979; Campbell & Stanley, 1966).

More specifically, cognitive ethnography emphasizes observation and key feature analysis of space, objects, concepts, actions, tools, rules, roles, and language. Study of these features can help the researcher determine the organization, transfer, and representation of information (Hutchins, 2010; 1995).

Ontology/Purpose

As stated, cognitive ethnography assumes that human cognition adapts to its natural surroundings. Therefore, the role of cognitive ethnographer is to transform observational data and interpretation into meaningful representations so that cognitive properties of the system become visible (Hutchins, 2010; 1995).

According to Hutchins (2010) study of the space where an activity takes place is a primary feature of observation in cognitive ethnography. He lists three kinds of important spaces for consideration (See Figure 2)

APPLICABILITY

Just as a book is organized to present information, games also structure narratives, and are themselves cultural artifacts containing representation of tools, rules, language, and context (Dubbels, 2008). This makes cognitive ethnography an apt methodology for the study of games, simulations, narrative, and human interaction in authentic context.

Because this emphasis on space is also indicative of current approaches to literacy (Leander, 2002; Leander & Sheehy, 2004); as well as critical science and the studied interaction between the internal world of the self and the structures found in the world, and how we communicate about them (Soja, 1996; Lefebvre, 1994); also from the tradition of ecological views on cognitive psychological perspectives (Gibson, 1986),; and in the case of the example, Discourse Processing (Zwaan, Langston, & Graesser, 1996). Because of the emphasis in ontology and purpose of the method align so closely with the variables identified in the Discourse Processing model (Zwann, Langston, & Graesser, 1996), it was applicable as a methodological approach to create a convergence of theory and tradition predicated upon an approach that aligns in purpose with analysis and question.

EXAMPLE

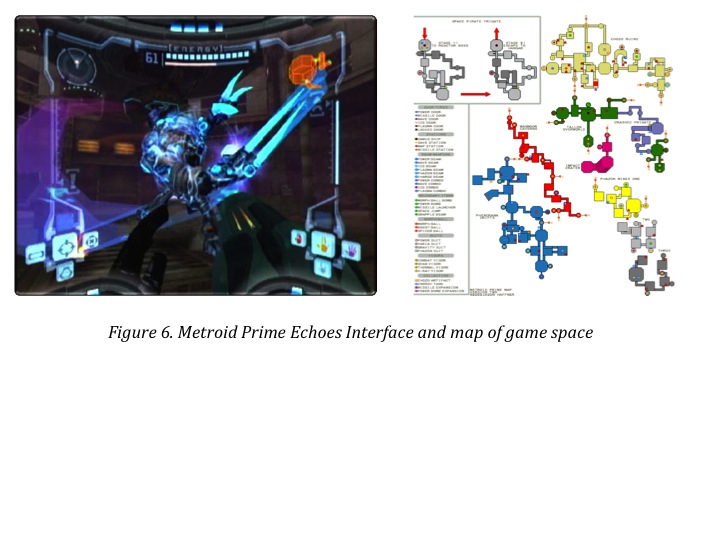

As an example, Dubbels (2008) used cognitive ethnography to observe video game play at an afterschool video game club. The purpose of this observation was to explore video game play as a literate practice in an authentic context. The cognitive ethnography methodology was recruited to utilize peer reviewed empirical research from laboratory studies—utilizing narrative discourse processing to interpret the key variables—to extend construct validity and observe whether the laboratory outcomes appeared in authentic, native contexts.

This allowed the researcher to interpret observations of authentic video game play in an authentic space through the lens of empirical laboratory work at an afterschool video game club.

Guiding question

The focus on space and social context, and the methodology for this example of cognitive ethnography explored a statement from O’Brien & Dubbels (2004, p. 2),