This monograph describes cognitive ethnography as a method of choice for game studies, multimedia learning, professional development, leisure studies, and activities where context is important. Cognitive ethnography is efficacious for these activities as it  assumes that human cognition adapts to its natural surroundings (Hutchins, 2010; 1995) with emphasis on analysis of activities as they happen in context; how they are represented; and how they are distributed and experienced in space. Along with this, the methodology is described for increasing construct validity (Cook and Campbell, 1979; Campbell & Stanley, 1966) and the creation of a nomological network Cronbach & Meehl (1955). This description of the methodology is contextualized with a study examining the literate practices of reluctant middle school readers playing video games (Dubbels, 2008). The study utilizes variables from empirical laboratory research on discourse processing (Zwann, Langston, & Graesser, 1996) to analyze the narrative discourse of a video game as a socio-cognitive practice (Gee, 2007; Gee, Hull, & Lankshear, 1996).

This monograph describes cognitive ethnography as a method of choice for game studies, multimedia learning, professional development, leisure studies, and activities where context is important. Cognitive ethnography is efficacious for these activities as it  assumes that human cognition adapts to its natural surroundings (Hutchins, 2010; 1995) with emphasis on analysis of activities as they happen in context; how they are represented; and how they are distributed and experienced in space. Along with this, the methodology is described for increasing construct validity (Cook and Campbell, 1979; Campbell & Stanley, 1966) and the creation of a nomological network Cronbach & Meehl (1955). This description of the methodology is contextualized with a study examining the literate practices of reluctant middle school readers playing video games (Dubbels, 2008). The study utilizes variables from empirical laboratory research on discourse processing (Zwann, Langston, & Graesser, 1996) to analyze the narrative discourse of a video game as a socio-cognitive practice (Gee, 2007; Gee, Hull, & Lankshear, 1996).

Keywords:

Cognitive Ethnography, Methodology, Design, Game Studies, Validity, Comprehension, Discourse Processing, Reading, Literacy, Socio-Cognitive.

INTRODUCTION

As a methodological approach, cognitive ethnography assumes that cognition is distributed through rules, roles, language, relationships and coordinated activities, and can be embodied in artifacts and objects (Dubbels, 2008). For this reason, cognitive ethnography is an effective way to study activity systems like games, models, and simulations –whether mediated digitally or not.

BACKGROUND

In its traditional form, ethnography often involves the researcher living in the community of study, learning the language, doing what members of the community do—learning to see the world as it is seen by the natives in their cultural context, Fetterman (1998).

Cognitive ethnography follows the same protocol, but its purpose is to understand cognitive process and context—examining them together, thus, eliminating the false dichotomy between psychology and anthropology.

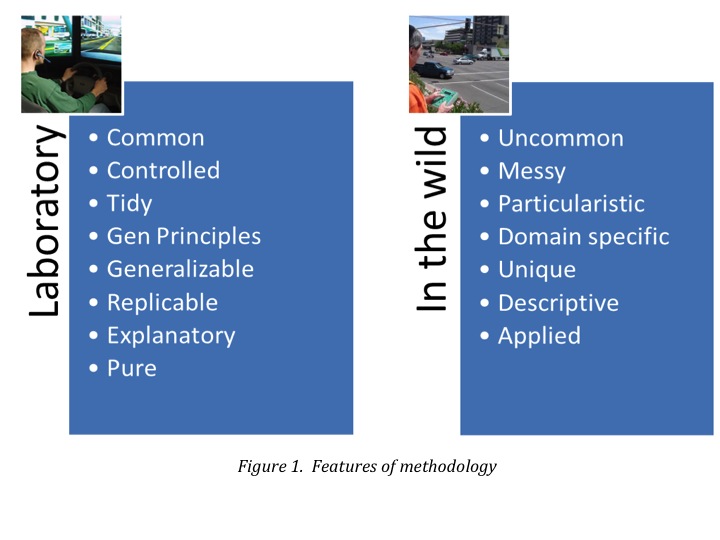

Observational techniques such as ethnography and cognitive ethnography attempt to describe and look at relations and interaction situated in the spaces where they are native. There are a number of advantages to both laboratory observation and in the wild as presented in Figure 1.

NOMOLOGICAL NETWORK

As mentioned, Cognitive Ethnography can be used as an attempt to provide evidence of construct validity. This approach, developed by Cronbach & Meehl (1955), posits that a researcher should provide a theoretical framework for what is being measured, an empirical framework for how it is to be measured, and specification of the linkage between these two frameworks. The idea is to link the conceptual/theoretical with the observable and examine the extent to which a construct, such as comprehension, behaves as it was expected to within a set of related constructs. One should attempt to demonstrate convergent validity by showing that measures that are theoretically supposed to be highly interrelated are, in practice, highly interrelated, and, that measures that shouldn’t be related to each other in fact are not.

This approach, the Nomological network is intended to increase construct validity, and external validity, as will be used in the example, the generalization from one study context, such as the laboratory, to another context, i.e., people, places, times. When we claim construct validity, we are essentially claiming that our observed pattern — how things operate in reality — corresponds with our theoretical pattern — how we think the world works. To do this, it is important to move outside of laboratory settings to observe the complex ways in which individuals and groups adapt to naturally occurring, culturally constituted activities.  By extending theory building with different approaches to research questions, and move from contexts observed in the wild, then refined in the laboratory, and then used as a lens in field observation.

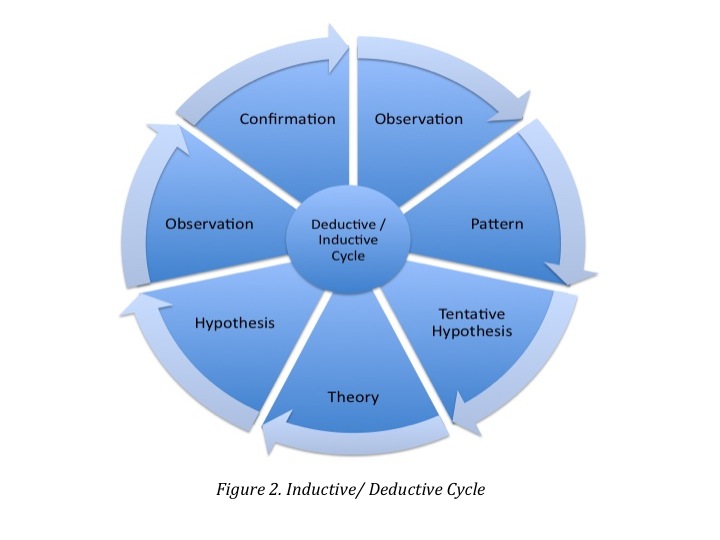

The pattern fits deductive/ inductive framework:

- Deductive: theory, hypothesis, observation, and confirmation

- Inductive: observation, pattern, tentative hypothesis,

These two approaches to research have a different purpose and approach. Most social research involves both inductive and deductive reasoning processes at some time in the project. It may be more reasonable to look at deductive/inductive approaches as a mixed, circular approach. Since cognition can be seen as embodied in cultural artifacts and behavior, cognitive ethnography is an apt methodology for the study of learning with games, in virtual worlds, and the study of activity systems, whether they are mediated digitally or not. By using the deductive/inductive approach, and expanding observation, one can contrast and challenge theoretical arguments by testing in expanded context.

Cognitive ethnography emphasizes inductive field observation, but also uses theory in a deductive process to analyze behavior. This approach is useful to increase external validity, operationalize terms, and develop content validity through expanding a study across new designs, across different time frames, in different programs, from different observational contexts, and with different groups (Cook and Campbell, 1979; Campbell & Stanley, 1966).

Cognitive ethnography emphasizes inductive field observation, but also uses theory in a deductive process to analyze behavior. This approach is useful to increase external validity, operationalize terms, and develop content validity through expanding a study across new designs, across different time frames, in different programs, from different observational contexts, and with different groups (Cook and Campbell, 1979; Campbell & Stanley, 1966).

More specifically, cognitive ethnography emphasizes observation and key feature analysis of space, objects, concepts, actions, tools, rules, roles, and language. Study of these features can help the researcher determine the organization, transfer, and representation of information (Hutchins, 2010; 1995).

Ontology/Purpose

As stated, cognitive ethnography assumes that human cognition adapts to its natural surroundings. Therefore, the role of cognitive ethnographer is to transform observational data and interpretation into meaningful representations so that cognitive properties of the system become visible (Hutchins, 2010; 1995).

According to Hutchins (2010) study of the space where an activity takes place is a primary feature of observation in cognitive ethnography. He lists three kinds of important spaces for consideration (See Figure 2)

APPLICABILITY

Just as a book is organized to present information, games also structure narratives, and are themselves cultural artifacts containing representation of tools, rules, language, and context (Dubbels, 2008). This makes cognitive ethnography an apt methodology for the study of games, simulations, narrative, and human interaction in authentic context.

Because this emphasis on space is also indicative of current approaches to literacy (Leander, 2002; Leander & Sheehy, 2004); as well as critical science and the studied interaction between the internal world of the self and the structures found in the world, and how we communicate about them (Soja, 1996; Lefebvre, 1994); also from the tradition of ecological views on cognitive psychological perspectives (Gibson, 1986),; and in the case of the example, Discourse Processing (Zwaan, Langston, & Graesser, 1996). Because of the emphasis in ontology and purpose of the method align so closely with the variables identified in the Discourse Processing model (Zwann, Langston, & Graesser, 1996), it was applicable as a methodological approach to create a convergence of theory and tradition predicated upon an approach that aligns in purpose with analysis and question.

EXAMPLE

As an example, Dubbels (2008) used cognitive ethnography to observe video game play at an afterschool video game club. The purpose of this observation was to explore video game play as a literate practice in an authentic context. The cognitive ethnography methodology was recruited to utilize peer reviewed empirical research from laboratory studies—utilizing narrative discourse processing to interpret the key variables—to extend construct validity and observe whether the laboratory outcomes appeared in authentic, native contexts.

This allowed the researcher to interpret observations of authentic video game play in an authentic space through the lens of empirical laboratory work at an afterschool video game club.

Guiding question

The focus on space and social context, and the methodology for this example of cognitive ethnography explored a statement from O’Brien & Dubbels (2004, p. 2),

Reading is more unlike the reading students are doing outside of school than at any point in the recent history of secondary schools, and high stakes, print-based assessments are tapping skills and strategies that are increasingly unlike those that adolescents use from day to day.

These day-to-day skills and strategies were viewed as literate practice and theoretically.

They led to the guiding question:

- Can games be described as a literate practice as has been described by theoreticians?

If so, this should be apparent through:

- Observing game play

- Understanding the game narrative and controls,

- And doing analysis of interaction and behavior. Â Â Should the words behind the bullets be capitalized since you have it in sentence form?

Hypothesis

The guiding question: whether games could be viewed as a literate practice was extended to create a hypothesis to test:

- Can the literate practice of gaming be used to facilitate greater success with printed text?

The hypothesis would be tested through examination of game play narratives and printed text narratives—as described in the Nomological network section; this would be an deductive/inductive process. The use of the variables from the Event Indexing Model could be used for identifying levels of discourse and the ability to create a mental representation after the inductive observation process.

The hypothesis was predicated upon the theory that familiarity with patterns in text, from symbolic representations such as words, sentences, images, and story grammars. The story grammar being “once upon a time,†in a game might be used as a developmental analog to help struggling readers predict the structure and purpose of print narratives by helping them to expect certain events, characters, and settings and help the reader to become more efficient. In essence, they would have expectations that “once upon a time†leads to “happily ever afterâ€, and other genre patterns attributable to transmedial narrative genre patterns.

The theory is that a reader may be capable of compensation, i.e., the use genre patterns and predictive inference as higher-level process in order to support lower-level process (Stanovich, 2000). It was proposed that to develop meaningful comprehension, the propositional and situation levels might be built upon for building mental representation of printed narrative text with the game.

Context and Variables for Coding and Analysis

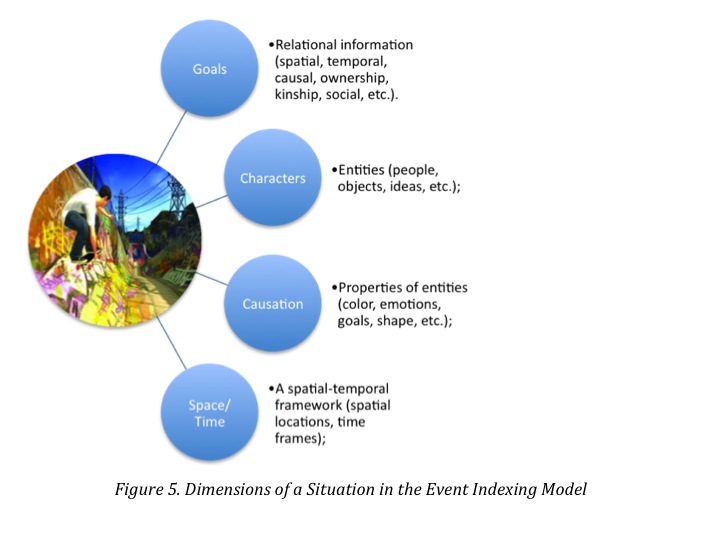

Literate activities were codified based upon a well-established model of discourse processing, The Event Indexing Model (Zwann, Langston, & Graesser, 1996). The Event Indexing Model offered five levels of discourse processing: Surface Level, Propositional Level, Situation Level, Genre Level, and Author Communication.

These levels offer an opportunity to view comprehension as a transmedial trait across discourse. The Situation Level (figure 5) is composed of two sub-levels of the variable. These are aspects of mental representation called the Dimensions of Mental Representation and are composed of: time, space, characters, causation, and goals.  These variables of the discourse-processing model were used to code the transcripts from the game club audio/video games, and context in order to explore the familiarity the students had with patterns in discourse, and their ability to recognize and process them. In order to observe the literate activities of students in their chosen medium, we offered the after school game club to students who had been selected by school district professionals for reading remediation courses outside of the mainstream. The video game play and activity space was analyzed from direct observation and analysis of audio/video recordings and photos taken during the activity.

The Situation Level (figure 5) is composed of two sub-levels of the variable. These are aspects of mental representation called the Dimensions of Mental Representation and are composed of: time, space, characters, causation, and goals.  These variables of the discourse-processing model were used to code the transcripts from the game club audio/video games, and context in order to explore the familiarity the students had with patterns in discourse, and their ability to recognize and process them. In order to observe the literate activities of students in their chosen medium, we offered the after school game club to students who had been selected by school district professionals for reading remediation courses outside of the mainstream. The video game play and activity space was analyzed from direct observation and analysis of audio/video recordings and photos taken during the activity.

Conceptual Space Analysis

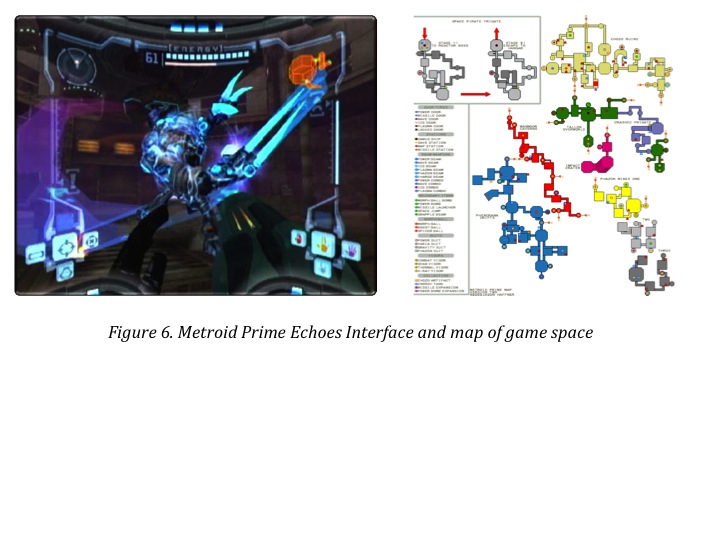

Walkthroughs of the game were used to look at decision making through navigation of the game.

A Walkthrough, according to Dubbels (in Beach, Anson, Breuch, & Swiss eds, 2009), is a document that describes how to proceed through a level or particular game challenge. Walkthroughs are created by the game developer or players and often include video, audio, text, and static images—offering strategies, maps through levels, the locations of objects, and important and subtle elements of the game.

In order to have a thorough understanding of possible the goals, actions, and behaviors available in the game, a number of walkthroughs were analyzed along with the game controls, and maps for optimal play—Figure 4.

Physical Space Analysis

To create the cognitive ethnography of the video game play, two video captures were used: one to record the screen activity, and one to record player interaction with the game and play space. Because the player of the game was often highly engaged with problem solving and reacting to the game environment, there was often little-to-no dialog or variation in expression and body language – however, play was often done in the company of others. This was informative as the discussion, encouragement, and advice displayed the social and cultural knowledge of the strategies of game play. In addition, a still camera was made available for the students to take pictures for their club. This included digital pictures of the games screens and each other playing, or whatever they felt was interesting.

Social Space Analysis

The audio and video, and still images were used for analysis of the social space, as well as the physical space. However, another level of data collection involved showing the player the video recording of their play and action in the room were used for a “reflect aloud†(Ericsson & Simon, 1983) for them to describe their play and social interaction. The key feature was not only observing the play, but also identifying theories of relationships, cognition and social learning—“what were you thinking there?†was the main question asked. This dialogue served to explain the player’s reasoning and decisions without overt interpretation by the observer. This enhanced the description, and connected the naturalistic game play to the laboratory, and then back to behavior in the wild.

It was this exploration of theory that led to the study of struggling readers using video games as methods for observing levels of mental representation and recall in game play and reading. Using the Cognition Ethnographic approach allowed for comparison of students observed playing video games with friends, the dialog and behaviors that constituted game play as a literacy (Gee, 2007; Gee, Hull, & Lankshear, 1996.) and their formal academic reading behaviors. Because the boys were observed in a formal laboratory setting, it was possible to make comparisons of their game play in the informal, or wild, autonomy supporting space.

Examples of Analysis

An example of the game play observation comes from Dubbels (2008, p. 265):

Since Darius seemed to know what he was talking about, he went next, and as he played, the other boys watched and were excited with what Darius was able to do. Darius seemed happy to demonstrate what he knew. While I was recording, the boys described Darius’ play and shared ideas enthusiastically about how the game worked and looked forward to their chance to play. As Darius made a move where he showed how to do a double bomb jump, the boys watched intently. The way it was explained was that you lay a bomb, and right before that bomb explodes, set a second one, then set a third just before you reach the very top of the jump. You should fall and land said the easiest way “is to count out: 1, 2, 3, 4.â€

And he laid the bombs on 1, 3, and 4. The boys were excited about this, as well as Darius’ willingness to show them. What was clear was that Darius had not only had played the game before, and as I questioned him more later I found that he had read about it and applied what he had read. He had performed a knowledge act demonstrating comprehension.

The other boys were eager to try some of the things Darius had shown them, and Darius was happy to relinquish the controller. What happened from there was that Darius watched for a while and then walked over to the Xbox, and then to the bank of computers. I left the camera to record the boys paying Metroid Prime and I walked over to see what Darius was doing. He showed me a site on the Internet where he was reading about the game. He had gone to a fan site where another gamer had written a record of what each section of the game was like, what the challenges were, cool things to do, and cool things to find. I asked him if this was cheating; he said “maybe†and smiled. He said that it made the game more fun and that he could find more “cool stuff†and it helps him to understand how to win easier and what to look for.

This idea of secondary sources to better understand the game makes a lot of sense to me. It is a powerful strategy that informs comprehension as described previously in this chapter. The more prior knowledge a person has before reading or playing, the more likely they are to comprehend it fully. Secondary sources can help the player by supporting them in preconceiving the dimensions of Level 3 in the comprehension model, and with that knowledge, the player may have an understanding of what to expect, what to do, and where to focus attention for better success. Darius has clearly displayed evidence that he knows what it takes to be a competent comprehender He had clearly done the work in looking for secondary sources and was motivated to read with a specific purpose—to know what games he wants to try and to be good at those games. His use of secondary sources showed that he was able to draw information from a variety of sources, synthesize them, and apply his conclusion with practice to see if it works.

One of the key features of the cognitive ethnography is the realization that even the smallest of human activities are loaded with interesting cognitive phenomena. In order to do this correctly, one should choose an activity setting for observation, establish rapport, and record what is happening to stop the action for closer scrutiny. This can be done with photos, video, audio recording, and notebook. The key feature is event segmentation, structure in the events, and then interpretation.

As was presented in the passage from Dubbels (2008), analysis was done describing the social network surrounding the game play of one boy describing the different spaces, and the behaviors of the boys surrounding him. The link to game play and strategy for successfully navigating the video game can be considered an analog to how young people read print text when a model is used as a framework for analysis.

One can then connect the cultural organization with the observed processes of meaning making. This allows patterns and coherence in the data to become visible through identification of logical relations and cultural schemata. This allowed for description of engaged learning when the video students approached the game, their social relations, and how they managed the information related to success in the game, reading the directions, taking direction from others, secondary sources, and development of comprehension during discourse processing compared to the laboratory setting.

In order to see if there was transfer, students were asked to work with the investigator in a one-on-one read aloud in a laboratory setting. The student was asked to read a short novel, Seed People, to the investigator for parallels and congruency between interaction of narratives found in game play, and traditional print-based narratives found in the classroom.

What I noticed in talking to them about Seed People was that they would read without stopping. They would just roll right through the narrative until I would ask them to stop and tell me about what they thought was going on, with no thought of looking at the situations and events that framed each major scene, and then connecting these scenes as a coherent whole as is described earlier in the chapter as an act of effective comprehension.

In one case Stephen made interesting connections between what he saw with an older boy in the story and the struggles his brother was having in real life. I just wondered if he would have made that connection if I had not stopped at the close of that event to talk about it and make connections. This ability to chunk events and make connections, as situations change and the mental representation are updated, is important for transition points in the incremental building of a comprehensive model of a story or experience.

When working to teach reading with this information, it is important to connect to prior knowledge and build and compare the new information to prior situation models or prior experience. Consider a storyboard or a comic strip where each scene is defined and then the next event is framed. Readers need to learn to create these frames when comprehending text. Each event in a text should then be integrated and developed as an evolution of ideas presented as each scene builds with new information; the model is updated and expanded.

If the event that is currently being processed overlaps with the events in working memory on a particular dimension, then a link between those events is established, then a link between those events is stored in long-term memory. Overlap is determined based on two events sharing an index (i.e., a time, place, protagonist, cause, or goal). (Goldman, Graesser, & van den Broek, 1999, p. 94)

In this instance with Stephen, there were many opportunities for analysis with the spaces described by Hutchins. The boy made connections to family outside of the novel, to his brother, to make it meaningful and also chunk a large section of the book as an event he could relate to. There was also the description of the setting, where Stephen was not pausing or processing the narrative in his reading. The activity did not include any social learning or modeling from friends and contemporaries, but resonated the controlled formal environment of school.

Thus, it was concluded that we must build our understanding in multiple spaces. The attributes of the situation model were made much more robust and much more easily accessible when prior knowledge was recruited and connected with the familiar..

Two types of prior knowledge support this in the Event Indexing Model:

• General world knowledge (pan-situational knowledge about concept types, e.g., scripts, schemas, categories, etc.), and

• Referent specific knowledge (pan-situational knowledge about specific entities).

These two categories represent experience in the world and literary elements used in defining genre and style as described from the Event Indexing Model. The theory posits that if a reader has more experience with the world that can be tapped into, and also knowledge and experience about the structure of stories, he or she is more likely to have a deeper understanding of the passage. In the case of the game players, it was seen to be important for seeking secondary sources, as well as copying the modeled behavior of successful players like Darius and segmenting action into manageable events. This was also evident when the students were asked to read aloud print text from the Seed People novel. The students, like Stephen showed they had difficulty segmenting events, or situations, just like they had difficulty with game play.

Of the fourteen regular students in the club, only two were successful with the games. After further interview and analysis, the two successful gamers, who showed awareness of game story grammar and narrative patterns were found to lack confidence in printed text. However, they were able to leverage the narrative awareness strategies from games to leverage print text form secondary sources in order to help them successfully p;ay the games. Conversely, the twelve students who struggled had to learn the help seeking strategies and narrative awareness.

CONCLUSION

For this study, cognitive ethnography was an appropriate methodology as it allowed for observation and analysis of the social and cultural context to inform the cognitive approach taken by the game players. It improved external validity from the laboratory study by applying the same construct to a new time, place, group, and methodology. The cognitive ethnography methodology presents an opportunity to move between inductive and deductive inquiry and observation to build a Nomological network. The cognitive ethnography methodology can provide opportunity to extend laboratory findings into authentic, autonomy supporting contexts, and opportunities to understand the social and cultural behaviors that surround the activities–thus increasing generalizability. This opportunity to use hypothesis testing in an authentic setting can provide a more suitable methodology for usability and translation for other contexts like the classroom, professional development, product design, and leisure studies.

References

Campbell, D.T., Stanley, J.C. (1966). Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research. Skokie, Il: Rand McNally.

Cronbach, L. and Meehl, P. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests, Psychological Bulletin, 52, 4, 281-302.

Cook, T.D. and Campbell, D.T. Quasi-Experimentation: Design and Analysis Issues for Field Settings. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1979)

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R.M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum Press.

Dubbels, B.R. (2008). Video games, reading, and transmedial comprehension. In R. E. Ferdig (Ed.), Handbook of research on effective electronic gaming in education. Information Science Reference.

Dubbels, B.R. (2009). Analyzing purposes and engagement through think-aloud protocols in video game playing to promote literacy. Paper presented at the National Reading Conference, Orlando, FL.

Dubbels, B. (2009). Students’ blogging about their video game experience.  In R. Beach, C. Anson, L. Breuch, & Swiss, T. (Eds.)  Engaging Students in Digital Writing.  Norwood, MA:

Christopher Gordon.

Ericsson, K., & Simon, H. (1993). Protocol analysis: verbal reports as data (2nd ed.). Boston: MIT Press.

Gee, J. P. (2007). Good video games + good learning. New York: Peter Lang.

Gee, J., Hull, G., and Lankshear, C. (1996). The new work order: Behind the language of the new capitalism. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Gibson, J. J. (1986). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Hillsdale, New

Jersey: Erlbaum

Hutchins, E. (1996). Cognition in the wild. Boston: MIT Press.

Hutchins, E. (2010). Two types of cognition. Retrieved August 15, 2010, from http://hci.ucsd.edu/102b.

Leander, K. (2002). Silencing in classroom interaction: Producing and relating social spaces. Discourse Processes, 34(2), 193–235.

Leander, K., and Sheehy, M. (Eds). (2004). Spatializing literacy research and practice. New York: Peter Lang.

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

O’Brien, D.G. & Dubbels, B. (2004). Reading-to-Learn: From print to new digital media and new literacies. Prepared for National Central Regional Educational Laboratory. Learning Point Associates.\

Soja, E. (1989). Postmodern geographies: The reassertion of space in critical social theory. London: Verso.

Soja, E. (1996). Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Stanovich, K.E. (2000). Progress in understanding reading. New York: Guilford Press.

Zwaan, R.A., Langston, M.C., & Graesser, A.C. (1995). The construction of situation models in narrative comprehension: an event-indexing model. Psychological Science, 6, 292-297.

Zwaan, R.A., & Radvansky, G.A. (1998). Situation models in language comprehension and memory. Psychological Bulletin, 123, 162-185.

Technology and Literacy

Current and Emerging Practices with Student 2.0 and Beyond

David G. O’Brien Brock Dubbels

Guiding Questions

- What technology tools and Web 2.0 applications are important for literacy learning

- What are the best practices involving technology and literacies

- How can instruction in the classroom and curriculum be enhanced by using new and evolving technologies that support digital literacy practices?

This chapter provides an overview of evolving research and theoretical frameworks on technologies and literacy, particularly digital technologies, with implications for adolescents’ literacy engagement. We suggest future directions for engaging students with technology and provide resources that support sound practices.

Evolving Research on Digital Technologies:

From Frameworks to Best Practice

When Kamil, Intrator, and Kim (2000) tackled a synthesis of research on technologies and literacy, they termed the task a conundrum. Given the rapidly evolving landscape of various technologies, that review, now dated (as this chapter soon will be), is still insightful both in reviewing a diversity of topics and the evolving importance of each. For example, at the turn of the decade, these researchers gave us historical footing in matters such as how computers and software may be used to improve reading and writing (Kamil, 1982), and to motivate learners (Hague & Mason, 1986). They noted the rising significance of hypertext and hypermedia, and foreshadowed the explosion of interest in the intersection of traditional literacies and digital media, which, at the turn of the decade, comprised a new program of inquiry (Reinking, McKenna, Labbo, & Kieffer, 1998). Finally, they also highlighted the social and collaborative importance of students working on stand-alone computers or in collaborative network environments, cited the paucity of research overall

on technologies and literacy, and expressed optimism about the future of computers as instructional tools.

In the same volume that featured the synthesis by as Kamil, Intrator, and Kim, Leu (2000) used the phrase “literacy as technological deixis†(p. 745) to refer to the constantly changing nature of literacy due to rapidly morphing technologies. Leu’s characterization is crucial, because he posits that these literacies are moving targets, evolving too rapidly to be adequately studied. If best practices rest on a solid research foundation, then, in the case of technologies and literacy we haven’t even begun to know what best practices are. Nevertheless, even in the midst of a shallow bed of “empirical†studies—that is, studies of specific effects, over time, with statistical power, or studies of carefully described and documented, contextualized practices—compelling frameworks have emerged, with implications for how technologies enable new literacy practices. Best practices, if based on solid frameworks rather than a carefully focused research program, can be extrapolated from the frameworks and be the basis for sound instruction and curriculum planning. In this chapter we bridge some of these frameworks with instructional practice.

The relatively brief evolution of technologies and literacy has led us from computers and software as self-contained instructional platforms to a networked virtual world that computers enable. In the past 10 years or so, we have moved from viewing the Web as primarily a source of information and as a sort of dynamic hypertext with increasingly sophisticated search engines, to Web 2.0. Albeit a fuzzy term that has accrued definitions ranging from simply a new attitude about the old Web to a host of perspectives about a completely new Web, Web 2.0 presents exciting possibilities for enhancing instruction and learning. This new Web is an open environment with virtual applications; it is more dependent on people than on hardware; it more participatory than a one-sided flow of information (e.g., blogging, wikis, social networks); it is more responsive to our needs (e.g., mapping a route to a previously unknown destination). Perhaps most important, Web 2.0 is more open to sharing of ideas, media, and even computer code (Miller, 2005). The presence of Web 2.0 is about the World Wide Web (WWW) as a platform for production. Software that users would normally purchase and install from a disk or download is now hosted on the Internet. In a sense, Web 2.0 affords anyone access to the largest stage yet conceived. Educationally, it has the potential to diminish the broadcast mode of information transmission that has reduced individual interests and engagement. Instead, learners can now have at their disposal studio-quality tools that enhance production, appreciation, recognition, and performance, and above all, provide access to a worldwide audience.

Whereas research on computers and reading and writing has remained sparse, research on the myriad literacy practices involved in the Web 2.0 phenomenon is sparse but growing rapidly and is informed by many theoretical frames and fields, most of which overlap—for example, multiliteracies (Cope & Kalantzis, 2000; New London Group, 1996), new literacies and new literacy studies (Coiro, Knobel, Lankshear, & Leu, 2008; Kist, 2005; Knobel & Lankshear, 2007), media studies and new media studies (Hobbs, 2007; Kress, 2003), and critical media literacy and popular culture (Alvermann, Moon, & Hagood, 1999; Beach & O’Brien, 2008), to name a few.

Each of these frameworks has its own dynamics for describing and studying literacy practices, and each is inextricably intertwined with other frameworks. In the rapidly emerging research base, most of the designs are highly contextualized and theoretically tantalizing, but few studies are gauged to identify specific generalizable practices. For example, the studies designed around some of the aforementioned frameworks vary in terms of methodology (spanning the full range of human and cognitive sciences); they vary in terms of which data are collected, which settings (physical and virtual) are studied, and how learners are defined (e.g., as information processors, real selves, virtual selves, identity constructors). Hence, we can present here only a small sampling and complement the descriptions with some “best practice†exemplars, reminding readers of the caveat that “research-based†practices represent glimpses or snapshots taken along the rapidly moving field.

Reader and Writer 2.0: New Literates and New Literacies

What is important about technologies and literacies, especially when considering adolescents? What should we cull from the myriad evolving frameworks and perspectives to be able to present something useful for teachers and learners at this point in time given this rapidly changing texture. First, we want to present the adolescent learner, the person we call Student 2.0, starting with a vignette.

High school students in Eden Prairie, Minnesota, a suburb of Minneapolis,posted photos on Facebook revealing themselves partying with alcohol, in violation of school rules. Following an investigation by school officials, disciplinary action was taken against 13 students. Students who believed that that the administration went too far walked out of school in protest; some of the parents threatened legal action (Xiong & Relerford, 2008). Scholars of digitally mediated popular culture challenged theadults, parents and school officials alike, to evaluate more critically what had happened: High school students felt a compelling need to express themselves as digital authors and document a relatively common practice, partying with alcohol. And issuing sanctions assumes that the practice had not been widespread before it was expressed publicly on Facebook. Prosecution of the rule offenders would only serve to remind the documentors to be more careful. The new media scholars also reminded the youth as authors to consider more carefully their audience in the future. When you post on Facebook, you create for everyone, including school administrators and parents. Some students who were interviewed on television reacted to the disciplinary measures by saying that their rights to free speech were violated, that the school administrators had no jurisdiction, because the activities happened off of school grounds. Others went back to Facebook to start a new group page to defend their actions.The Eden Prairie incident, albeit intriguing as a local interest piece about controversial legal and ethical issues regarding the Web 2.0, illustrates the trend of online content creation among youth. Rather than just use the Web to locate information, students are involved in content creation, that continues to grow, with 64% of online “teenagers†ages 12 to 17 engaging in at least one type of content creation, up from 57% of online teens in 2004 (Lenhart, Madden, Macgill, & Smith, 2007). In this national survey by the Pew Internet and American Life Project, 55% of online teens ages 12–17 say that they have

created a profile on a social networking site, such as Facebook or MySpace, and 47% of online teens claim to have uploaded photos where others can see them. Even though those students posting online photos sometimes restrict access, they expect feedback. Nearly 9 out of 10 teens who post photos online (89%) say that people comment on their postings at least some of the time. The number of teen bloggers nearly doubled from 2004 to 2006, with girls leading boys in blogging, and the younger, upcoming girls more likely to outblog The important issue for teachers is that these student authors are composing in a visual mode and reading comments printed in response; their peer readers (who are also most likely composers) are increasingly “reading†images and composing text responses or print messages in blogs and expecting critical responses. In short, students increasingly seem to engage in the

types of reading and writing they either don’t engage in, or don’t prefer, at school.

Experienced teachers can remember when stand-alone computers were going to revolutionize education; they can recall when the Internet was a cumbersome, text-based environment rather than an engaging graphical environment called the WWW. Those of us who, as literacy educators, have spent our careers studying how young people interact with printed texts are now faced with a new landscape that renders many of our theoretical models, instructional frameworks, and “best†practices based on these print models inadequate or even obsolete. Print text remains important but, as noted, expression is increasingly multimodal (Kress & Van Leeuwen, 2001). Reading and writing youth are increasingly likely to express ideas using different semiotic modes, including print, visual, and audio modes, and to create hybrid texts that defy typical associations between modes and what they traditionally represent.

When David worked with struggling readers in a high school Literacy Lab, the students, many of whom did not choose to read and write using print, wrote complex multimodal texts on a range of topics. They were very articulate about the affordances of various modes, and how those affordances influenced their choices in composition. For example, one group of students working a project exploring the impact of violence in the medion in adolescents, decided when to use images instead of print to communicate their ideas more effectively and passionately. They carefully planned how to juxtapose images and print to convey meaning. What would traditionally have been termed a “report†was instead a mul- timedia project, which they presented to parents and others at the school Open House evening. Brock has created a game studies unit, in which students study the qualities of their video games and create a technical document called a Walk- through using blogs, a wiki, video, and an animated slide show embedded into the blog. Students could read, compare, and evaluate other students’ work. Brock used an RSS feed (really simple syndication, a feed link to syndicated content) and had the blogs collected with bloglines, a way to both aggregate the student work and provide social networking through the WWW-based platforms and the comment sections for students.From these two examples, you can see that the reading and composition enabled by these digital technologies is spatial rather than linear. Linearity has been replaced by reading and writing in virtual textual space—where a hot link lures the reader away from one page and on to the next, and from print to images and video, deeper and deeper into one’s unique textual experience, and writers can post, broadcast, and receive responses. Scholars are already starting to look at the new spatial and temporal dimensions of digital literacies, as well as the compatibilities and incompatibilities of these dimensions

with traditional spatial and temporal dimensions of schools (Leander, 2007). Researchers are also studying new literacy environments such as web pages using research paradigms derived from reading print on paper—for example, Coiro and Dobler’s (2007) work extending traditional comprehension theories to study online reading comprehension. Coiro and Dobler argue that although we know a lot about the reading strategies that skilled readers use to understand print in linear formats, we know little about the proficiencies needed to comprehend text in “electronic†environments. McEneaney (2006) cogently argues that the traditional theoretical frameworks, including so-called “interactive theories†(from cognitive or transactional perspectives) are too strongly based in a traditional notion of print to be useful. With what are the new literates interacting? McEneaney contends that the text can “act on†the environment: The text can create the reader, just as the reader through the dynamics of online environments, can create or change the text.

But the new literates also encounter new challenges. The new textual spatiality lacks the kinesthetic texture of books; readers lose their “places†and even the ability to feel the touch of the page as they do when they flip paper pages back, then reorient themselves on the page (Evans & Po, 2007). The feel of the text is replaced by the feel of a finger on a mouse or a key. The imaging that helps a reader maintain and access the previous page might be replaced by multiple mental images of more rapidly changing texts, or mental images replaced by actual images. What Evans and Po call the fluidity of the digital or electronic texts invites readers to alter the text more readily, more easily. We come full circle with a tension faced by readers of the digital texts. On the one hand, this text fluidity begs readers to alter texts, to pick alternative texts, and to mix and match texts; on the other hand, this new textuality, with texts unfolding at every mouse click, places the text itself more in the control of the reader. The text the reader creates, often unwittingly via a series of clicks or cuts and pastes, may address the reader/writer in unexpected ways. One of the most exciting prospects for educators is the unlimited range of texts, from traditional print modes to various hybrids, including print texts, visual texts, audio texts, and even various types of performance texts that students can now create, as they themselves are “created†or changed by those texts. The new literates can navigate through a collage of print, images, videos, and sounds, choosing and juxtaposing modalities, and bending old spatial and temporal constraints to communicate to peers and to others throughout the world.

Beach and O’Brien (2008), in drawing from both the philosophy of mind and neuroscience (e.g., Clark, 2003; Restak, 2003) propose that the students of the “digital generation†have more digitally adept brains; they read and write differently than youth from even 10 years ago, because their existence

in the mediasphere, the barrage of multimodal information they encounter daily, the constant availability of multiple tech tools at their fingertips, and the convergence enabling immediate use and production of media have changed the way they process multimedially. Prensky (2001) has posited a similar scenario. The Beach and O’Brien proposal (2008), in response to a Kaiser Family Foundation study (Foehr, 2006) of young people ages 8–18 and widely disseminated in the popular press, shows that even though the total amount of time devoted to media use remains about the same as 5 years ago (6.5

hours a day), the amount of time devoted to multitasking, using multiple forms of media concurrently (e.g., surfing the Web while listening to an MPEG-1 Audio Layer 3 (MP3) and checking text messages), is on the rise. Beach and O’Brien (2008) contend that multitasking is not accurate, because it implies the ability to engage in several activities at the same time or, more accurately,to switch attention rapidly among activities to gain efficiency in completing work. They instead characterized this often seamless juggling as multimediating (Lankshear & Knobel, 2003), because it more accurately involves not only multimodal attention shifts but also seems to include a new facility and flexibility in processing and producing multimodal texts. The missing piece in characterizing the new literates is that we continue to appraise them using outdated models of reading, text processing, and learning. Instead, we need

to think of them as more adept at using technologies to read, compose, and “socialize.â€

Texts 2.0: From the Page to the Screen

Let us revisit the question posed in the last section—What is important about technologies and literacies?—and this time consider the evolving kinds of texts that youth are reading and writing. Again, we have to choose among compelling frameworks and perspectives. One salient issue surrounding the

evolving technologies is how the notion of “text†is changing. We are “moving from the page to the screen†(Kress, 2003). Kress notes that the screen privileges images. He also makes a case for the ambiguity of images and the necessity of print text for helping the viewer understand context and make a

directed interpretation of images. As educators, we have to concede that texts are increasingly multimodal (Jewitt & Kress, 2003). In multimodal reading and composing, ideas and concepts are represented with print texts, visual texts (photographs, video, animations), audio texts (music, audio narration, sound effects), and even dramatic or other artistic performances (drama, dance, spoken-word) (O’Brien & Scharber, 2008).

A second change is the increasing popularity of hybrid texts that are unlike most of the longer, connected discourse with which many of us grew up. For example, textoids are on the rise. These texts were originally defined as specially created research texts that lacked the coherence and structure of naturally occurring texts from typical genres (Graesser, Millis, & Zwaan, 1997) or contrived instructional texts (Pearson, 2004). Ironically, these once- contrived texts are ubiquitous in online environments. The term textoids now refers to fleeting texts that are transported from one place to another and are constantly changing (e.g., Wikipedia entries, pasted into a student’s report and edited to fit into the new textual context); they are also textual bursts of information sent to cell phones as text messages. Short textoids or text bursts are displacing longer discourse as readers expect more choices in accessing information and entertainment faster in quick clicks. At the same time, the sheer number and range of genres of these textoids, the juxtaposition of textoids with other media, and the retention of the more traditional, longer discourse, makes reading in online text environments more challenging than reading in traditional print environments.

The typical ways of describing and distinguishing texts from one another, such as using text structure, no longer apply (McEneaney, 2006). Electronic texts defy such classification, because they may be short and contrived to produce a targeted burst to get attention (the textoids); they are not linear but

spatial (hypertexts, hypermedia). Single textoids or pages or articles are linear, but they exist in virtual space, with a multitude of other possible texts. In short, the texts have virtual structure that is much more dynamic than static structures assigned to single print texts.

Present Technology Tools and Web 2.0 Applications

As we noted, Web 2.0 tools are about production, and they are hosted on the Web to enable a range of activities. As the access to bandwidth increases, and computers are equipped with greater image/video processing capacity, these tools will become invaluable in engaging youth. Young people will use these tools not only to develop literacy and numeracy skills but also to continue to hone their technological skills in the production, communication networking, data mining, and problem solving that are increasingly valued in the global economy. In the past, many of the tools now available as Web-based tools were expensive, limited to single machines, and difficult to use. These same tools, such as word processing, multimedia production, and network communications tools are now free, shareable, collaborative, and perceived as both meaningful and enjoyable by young people. Moreover, the tools are

part of young people’s daily lives. In addition, the personal electronics that many young people carry in their pockets, backpacks, and purses are more powerful than the computers that inhabited labs not even 5 years ago. With the advent of new applications and relatively cheap storage on the Web, these portable devices neither perform the bulk of processing nor store the outputs of processing; they are access devices—Web portals, with small screens and keyboards or other ways to input data. For example if you want to work with pictures, you can access a portal such as Flickr to view and manage pictures; if you want to create a document of just about any stripe, you can go to Google Docs and make slide shows; engage in word processing; construct spreadsheets; and store, share, and collaborate with writing partners.

Teachers can use many of these tools to extend and to enhance the learning experience of their students. The tools present challenges in developing best practices because they are neither repositories of content nor self- contained curricula. Rather, they can be used by creative teachers who are

able to draw from existing content domains, themes, and conceptual frameworks as they work within the applications; the tools can provide supportive environments for producing content, sharing and collaborating around content, and hosting public displays of users’ productions. Hence, the tools are not useful without the context of a larger unit or lesson plan, and instructional and learning frameworks that support activities and literate practices enabled by the tools. Teachers must understand clearly their instructional and learning objectives and goals, and students must know how the tools can help them meet those goals. Otherwise, the tools, which students sometimesknow well and can use for entertainment, revert to users’ tools for pleasure and interests, easily circumventing instructional or learning practices desired by teachers. Next, we review some Web 2.0 tools that enable these practices, and describe the features of each, presenting examples of how we have used them with students.

MySpace

We start with the nemesis of most computer classrooms and labs. For example, Brock was observing another teacher’s students during a drafting class. The students were working in a lab with high-end three-dimensional drafting software. During downtime between instructions that were broadcast over the

public address system, students often checked their MySpace pages. Although the site was blocked in the district, many students easily overcame the obstacle by searching for a proxy server that granted them access. A proxy server is a website that has a name accepted by the firewall, so it is allowed—it is kind of like using a fake ID. Although students may not know how it works, they have learned how to do it. And no matter how savvy the information technology (IT) department, the almost infinite supply of new proxy servers and webpages, with directions targeting youth who want to jump the school restrictions, makes sites deemed objectionable by school districts difficult to block.

On the one hand, to the digital immigrants and the inhabitants of the Institution of Old Learning (O’Brien & Bauer, 2005), MySpace represents an uncontrolled virtual space that distracts students from work and enables socializing and forms of expression incompatible with the organization and temporal control of school. On the other hand, for digital natives, “assimilated†digital immigrants, and new literacies advocates, MySpace is a dynamic forum of multimodal expression. It is also a place where young people socialize with peers around the world, put pictures up, write in slang, stream music and video, and engage in instant messaging. They are able to blog, to embed flash animations—in short, to engage in almost limitless expression using a range of multimodal literacies. It is really an example of students expressing themselves in the same way they dress, decorate their rooms, or draw in their notebooks.

This does not mean that the space is benign. Although you can connect with friends and family, you can also get solicitations from unwanted characters. Most young people are aware of whom to talk to, and how they expect others to speak to them. Users know that others mask their true identities through the computer, which has led young people to be more savvy as well. The Kaiser Family Foundation Generation M report (Roberts, Rideout, & Foehr, 2005) notes that when kids come across inappropriate sites and solicitations, they move past them. For digital natives, experienced in social networking, these are just another distraction in the way of what they went to the site to do. MySpace sites can also be locked to persons other than those invited by the owner.

We don’t expect sites like MySpace to be imported into the school curriculum. However, in the spirit of being more assimilated into Generation M’s world, it makes sense for teachers to join MySpace, set up a page, and even let students know that you have done so. As teachers, we interact regularly with our students via MySpace. Through it, we are more in tune with their social worlds, their interests, and their creativity. You might also want to bridge media production in school with the sharing features of such social networking sites, so that students may use tools like MySpace as a way to share and to get feedback on their productions.

You already know a bit about Facebook from the Eden Prairie vignette. It is a place where you can post your profile and surround yourself with friends, their activities (including photos of parties!) and favorite sites, and connect the dots to all of your websites. Brock has links to SlideShare, mogulus television station, Facebook social networking groups, and various blogs. Facebook also includes tons of little games, multiple ways you can communicate with others, and things you can share. Brock is a member of many groups, and when the mood catches him, he starts another group: How about people who have read this chapter and want to continue the discussion about literacies involved in applications for Student 2.0? It really is that easy, and he really did start that group.

In Facebook you can choose to keep up with friends you don’t see often, as well as friends and acquaintances with similar interests and affinities. You can take surveys of movies and compare them to your friends; you can see what kind of German or French philosopher you are. You can share music,

keep up to date with friends through instant messaging, and be alerted to activities of groups to which you belong. Facebook, like MySpace, is blocked in many school districts, although most of adolescents we know seem to prefer MySpace. As with MySpace, we encourage teachers to set up a Facebook account to see what it provides. Although it might be tricky if the site is officially blocked in school, we also encourage teachers to use it to network with both colleagues and students. One of the great revelations, if you are included as a “friend†to students classified as “struggling†in reading and writing, is the quality, the range of genres, and the passion with which these students compose and engage in reading others’ compositions on social networking sites. It is possible that these same students, who have negative perceptions about their abilities and avoid reading and writing in school, might invite teachers to read what they have written online.

YouTube

Unfortunately, YouTube is much maligned in schools, not just because of the content, but also because streaming media consume bandwidth. This is the most complete compendium of online searchable video ever. Like any compendium, including the billions of webpages outer there, there are some videos

that teachers may find either objectionable or a waste of time, just as there are thousands of interesting and informative videos. There are really many opportunities for using Web-based video in the classroom. Here are several ways that we have used it:

1. To show a video.

2. To host a video we have produced.

3. To engage in social networking.

4. To enhance engagement among students.

5. To provide content for a Web-based, TV-like network with Mogulus. Â Â (now Livestream)

The real value of video is its impact due to availability of narrative, and the power of performing and presenting to the world—something that local and even national networks cannot do. YouTube not only hosts videos created by your students but also provides access to videos created by novices and professionals from all over the world. YouTube should be a part of classroom instruction designed to teach appropriate use of media and media savvy to young people. With YouTube you can embed video in your blog and your website, as well as upload your own creations—even from your cellular phone. We have observed that when students create for performance and presentation to an audience other than their teachers and immediate peers, they put forth much more effort and are much more creative and engaged, and the learning experience lasts long after the week-and-a-half extinction point of most test- driven curricula. Students can create, post, and share. In addition, teachers can create groups and utilize social networking to perform and to respond. The most powerful benefit is that this social networking and broadcasting function extends and deepens the possibility of participating in high-traffic media networks, where millions of people may view your work and send out links to invite their friends to see what you have done. With the right topic and a bit of luck, a cell phone with video capture and a good idea can start a person’s career in video media. This prospect can be motivating, and the idea that students have done something that everyone can see leads them to some real street “media cred.â€

Flickr

This photo sharing website, web services suite, and online community platform was one of the earliest Web 2.0 applications. In addition to being a popular website for sharing personal photographs, the service is widely used by bloggers as a photo repository. Flickr’s popularity has been fueled by its innovative online community tools that allow photos to be tagged and browsed by folksonomic means, a social/collaborative way to create and manage tags for content, in contrast to traditional subject indexing, in which content is fit to subjects predetermined by experts (Vander Wal, 2007). In Flickr, metadata are generated by not only experts but also creators and consumers of the content. Folksonomies became popular on the Web around 2004, with social software applications such as social bookmarking or annotating photographs. Typically, folksonomies are Internet-based, although they are also used in other contexts. Folksonomic tagging is intended to make a body of information increasingly easy to search, discover, and navigate over time.

As folksonomies develop in Internet-mediated social environments, users can discover who created a given folksonomy tag, and see the other tags that this person created. In this way, a folksonomy user may discover the tag sets of another user who similarly interprets and tags content. The result is often an immediate and rewarding gain in the user’s capacity to find related content (a practice known as pivot browsing). Part of the appeal of folksonomy is its inherent subversiveness: Compared to the choice of the search tools that websites provide, folksonomies can be seen as a rejection of the search engine status quo in favor of tools that are created by the community. Obviously, in addition to being a place to share photos, Flickr is a great source of media form students’ multimedia productions.

Blogger

Brock has used this one, putting his class blog (www.5th-teacher. blogspot.com) up on the screen, with images, examples, links to other resources, related news events, goings on in the class, his teaching manifesto, and global descriptions of assignments, as well as breakdowns of daily work. He also embeds his slide shows in the blog, along with video. This provides a resource for students to use both in class and outside of class. Because students have learned the format, and how to use pictures and other media from the Web, they have become proficient at creating reflective work and high-quality

multimedia productions. Blogger gets a bad rap by some, but you can limit the audience of student blogs by closing them off from the world feature and selecting viewers by inviting specific people. This also allows the teacher to access the blog if there is questionable content for classroom blogs “gone rogue.â€

SlideShare

This Web application is great for getting students to see the opportunities of creating active multimedia products. Brock’s students created slide shows in PowerPoint, using images, text, and animation and transition effects, then uploaded them to SlideShare. This allowed the class to create their own group (Washburn Introduction to Engineering Design [IED]) where they could see and comment on each others’ slides, as well as use the chat function. Students also use SlideCast, in which they enter and synchronize an MP3 with their presentation, so that both teachers and students can create music videos or even do voice-over narration for telling stories and performance (dramatic) readings. SlideShare also lets you one-click to Blogger, so that students may embed their slide show in their blog. A cool feature is the ability to link this into Facebook.

Google Suite

Google provides a nice suite of tools for educators and students. Often your students have computers with Internet access at home but lack productivity software, such as Microsoft Office, or free tools such as OpenOffice. Students can use the Google Suite to create word processing, slide shows, and spreadsheets. The impressive feature is that this suite is available online, so students with an Internet connection can work at home on the document they created at school. And as with other Web 2.0 applications, students may invite others to cowrite and produce documents here. This allows groups to work on the same paper, and it also tracks each person’s contributions as the document is created. We used Google Documents to collaborate on this chapter. In addition, Google Maps, Google Earth, and Google SketchUp, a three-dimensional modeling program, are other tools in the Google suite that deserve extra emphasis. Reading and writing practices are more engaging to students when tied to the creation of the places, people, and activities. Brock had students create scenes from the play A Raisin in the Sun using this tool. The class explored the role of place and lived space, and the way space influences how people feel, speak, and act. This high-tech diorama was reminiscent of the shoebox versions we sometimes made for fun or for school projects.

Zotero

Zotero, an easy-to-use yet powerful research tool, helps researchers gather, organize, and analyze sources (citations, full texts, webpages, images, andother objects), and share research results in a variety of ways. An extension of the popular open-source Web browser Firefox, Zotero includes the best parts

of older reference manager software (like EndNote)—the ability to store author, title, and publication fields, and to export that information as formatted references—and the best parts of modern software and Web applications (like iTunes and del.icio.us), such as the ability to interact, tag, and search in advanced ways. Zotero integrates tightly with online resources; it can sense when users are viewing a book, article, or other object on the Web, and—on many major research and library sites—find and automatically save the full reference information for the item in the correct fields. Since it lives in the

Web browser, it can effortlessly transmit information to, and receive information from, other Web services and applications; because it runs on one’s personal computer, it can also communicate with software running there (e.g., Microsoft Word). It can also be used offline (e.g., on a plane, in an archive without Wi-Fi).

Scribd

This document-sharing community and self-publishing platform enables anyone to publish easily, distribute, share, and discover documents of all kinds. You can submit, search for, and comment on e-books, presentations, essays, academic papers, newsletters, photo albums, school work, and sheet music. A powerful feature of this tool is that you can upload documents in many different formats, including Microsoft Word, Adobe Portable Document Format (PDF), plain text, hypertext markup language (HTML), PowerPoint, Excel, OpenOffice, Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG), and many other formats. Once your documents are uploaded, you can embed them in a blog, Facebook profile, or other external websites, with your fonts, images, and formatting fully intact. Each document hosted at Scribd has its own unique uniform resource locator (URL), and you have unlimited storage, so you can

upload as many documents as you like. Once these are up, they are also available for fast indexing by Google and other major search engines, so that your content can be found in simple searches. You can keep certain documents private or share with a limited number of friends, and you can automatically convert published content into PDF, Word, and plain text. What is engaging for young writers is that not only can they publish widely but they also can see how many people have viewed their documents by location. Through Google you find documents similar to your own, as well as connect with a community of writers working in the same content area, enabling feedback and dialogue about your documents yet allowing you to retain full copyright under Creative Commons licenses.

Other Web 2.0 Resources

Space limits preclude a more elaborate listing of the multitude of other Web 2.0 sites. We recommend that readers of this chapter peruse the following briefly annotated list of other sites promoting multimodal literacies:

• Digg. A community-based, popular news article website, where news stories and websites are submitted by users, then promoted to the front page through a user-based ranking system.

• bubbl.us. An online brainstorming tool that students and teachers can use to create colorful mind maps online, share maps and collaborate with friends, embed mind maps in blogs or websites, e-mail and print maps, and save maps as images.

• BigHugeLabs.com. A tool that makes using Flickr a lot more interesting by capitalizing on the site’s existing functionality. Dozens of toys, games, and utilities allow you, for example, to create a magazine cover from a selected Flickr photo, create a motivational poster, and access huge amounts of user    data (FlickrDNA).

• Photoshop Express. An application providing two gigabytes of storage to which you can link in your blogs or websites. You can edit images on the fly without having to up/download them each time or move from computer to computer, and you are just a login away from your library of photos.

• SoundJunction. A site where users can take music apart and find out how it works, create music, find out how other people make and perform music, learn about musical instruments, and look at the backgrounds of different musical styles.

• del.icio.us. (pronounced like the word delicious). A social bookmarking Web service for storing and sharing data with more than 3 million users and 100 million bookmarked URLs.

• Ning. A site that enables the creation of one’s own social network, designed to compete with sites like MySpace and Facebook, by appealing to users who want to create networks around specific interests, or who have limited technical skills.

• VoiceThread. A versatile online media album that can hold essentially any type of media (images, documents, and videos) and allow people to make comments in five different ways—using voice (with a microphone or telephone), text, audio file, or video (with a webcam)—and share them with anyone they wish.

• Many Eyes. A tool for the visual representation of data that makes sharing data creative and fun, while tuning students into the relation between information presentation and interpretation.

• Scratch. A designing tool with a language that makes it easy to create interactive stories, animations, games, music, and art.

Classroom Vignettes of Practices with Technologies and Literacy

Junior High “Intervention†Class

We have studied our reading/writing intervention class in a suburban community of the Twin Cities for 3 years (O’Brien, Beach, & Scharber, 2007). The class uses a Literacy Lab setting with a reduced enrollment target of 15 students, previously assessed as struggling in reading, and mentored by two

teachers, both of whom hold K–12 reading licenses. The class meets once a day in a block scheduling format, with 93-minute class periods. The curriculum juxtaposes traditional engagement activities with “new literacies†activities. For example, on the side of more traditional interventions, students use

the Scholastic READ 180 program, read and discuss young adult novels as a group, and dramatize the texts and a range of activities to integrate reading and writing. They also engage in strategies instruction, such as the use of mind mapping and various activities designed specifically to help students achieve competence on state language arts standards and high-stakes assessments. On the new literacies side, using various technology tools, the students engage in writing activities, such as producing stories, comic books (using Comic Life), wikis (in Moodle) and poetry writing. They write journal responses to their reading and construct PowerPoint presentations about topics, such as their favorite video games or young adult novels, and share their poetry or story writing. They plan, design, and perform radio plays (using GarageBand for background tracks and sound effects). Recently, students completed placebased projects in which they used VoiceThread to publish photos of important places in their school, complete with audio or print commentaries. They publish their writing in the school district Moodle site. Some of the students also participate in afterschool computer gaming sessions. In the new literacies realm, the teachers include practices in which students engage to explore ideas, construct a classroom community, and develop agency in meeting personally relevant goals.

Media Class Rhythm and Flow Unit

This was the first unit that Brock created after transitioning from a language arts teacher to a media specialist. He found that the units he taught as a language arts teacher were still very applicable to the standards and benchmarks in media technologies when it came to teaching media or print texts, or the many opportunities that arise as a result of having access to computers. As a media specialist, Brock tried to link the media and technology activities to improvement in reading and writing. For example, he included Reading Friday, in which students had to create a music business persona/image, describe their style of music, and choose lyrics that they would perform and record into Garage Band. GarageBand is one option. Students could also use one of the Web-based products we have discussed. So the students took print texts—poems, paragraphs, dialogue, and lyrics they liked—and recorded themselves reading as a track on the music software. They also recorded outtakes, or descriptions of the experiences, and rated their oral interpretation performances. After students had shared their tracks with Brock, they began to practice putting a beat and music behind the tracks. This enabled a thorough interpretation and exploration of voice and oral expression. Students who had never really thought about the qualities of the voices in the narratives (e.g., the tone, theme, pitch, volume, emphasis in elongation and breaks) could better hear and understand dramatic pauses, tone and volume changes, diction and word choices, as well as format, organization, and punctuation. This activity began to make a difference in students’ understanding of these concepts. As students began exploring pauses work, changing and emphasizing words, assonance, and resonance in rhyme structures, they were really looking at oral reading and fluency, and reading in general, in a much deeper and more playful way. Students then took photos and made their CD covers, using image manipulation software; they made their own liner notes and wrote their own copy for advertising; they conceptualized a MySpace design (because they were not permitted access to MySpace) and created tours, clothing, and so on. It turned into a game about being in the music business. This unit, which had originally been intended as a week-long reward for the kids, so engaged students as they performed their lyrics and created their music careers that Brock extended it for 2 weeks.

What are “best practices†in these scenarios? First, students engage in activities, using technologies that support both the local curriculum and state standards. Rather than considering technologies and innovation as replacements for more traditional instructional and learning, the technologies provide

more effective ways to engage students. Second, best practices dictate that the technologies enhance teaching and learning by providing access to media and enabling students to use various modalities to explore and publish ideas. Third, although we can already see a future in which digital literacies replace traditional print literacies, for now, given the realities of standards, print-centric assessments, and, particularly the predominately print-based curricula, best practices explore ways to bridge print and digital literacies effectively. Fourth, the notion of best practices, which we typically associate with teaching or facilitating learning, should be extended to include practices related to supporting infrastructures and increasing funding for technologies that do enhance teaching and learning.

Future Directions and Best Practices for Engaging Students in Literacy with Technology